Abstract:

Since the dawn of the new millennium, humanity has been confronted with many problems. These include starvation, poverty, racism, ethnic hatred, wars, terrorism, genocide, environmental pollution, illegal immigration, violence, street crimes and intolerance. In order to solve these issues, education can play an important role; it can also render our world both pleasanter and kinder. Moreover, education can help students to develop skills for practical thinking, problem solving and co-operating with each other. Besides encouraging creativity, innovation and communication, peace education can drive students towards a more conscientious, tolerant, peaceful and democratic way of thinking.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8374

Languages: Türkçe, English, Deutsch

İnsanlık yeni bin yılın başında açlık, yoksulluk, ırkçılık, etnik nefret, savaşlar, terörizm, soykırım, çevre kirliliği, yasadışı göç, şiddet, sokak suçları ve hoşgörüsüzlük gibi problemlerle karşı karşıyadır. Eğitim, yukarıdaki sorunların çözümünde ve dünyayı daha yaşanabilir bir yer haline getirmede önemli bir rol oynayabilir. Bu amaçla öğrencilere, etkili düşünme, problem çözme, yaratıcılık, yenilikçilik, işbirliği ve iletişim gibi beceriler kazandırılmalıdır. Bunun yanında barış eğitimi yoluyla, öğrencilerin vicdanlı, hoşgörülü, barışçıl ve demokratik olabilme nitelikleri de geliştirilmelidir.

Barış Eğitimi Nedir?

Barış eğitimi, çatışma oluşumunu önlemek için gerekli bilgi, beceri ve tutumların geliştirilmesi ve aynı zamanda çatışmaların barışçıl yollarla çözülmesi ve barışa elverişli sosyal koşulların yaratılmasını kolaylaştırmaktır.[1] Başka bir deyişle barış eğitimi, öğrencilerde barış yollarını benimseme bilincini yaratmak için barışla ilgili eğitim süreçlerdir.[2] Barış eğitimi aynı zamanda barış içinde yaşama isteğini geliştirmeli ve toplumun dayandığı barışçıl değerlere vurgu yapmalıdır.[3]

Tarih Eğitimi Barış Eğitimini Nasıl Desteklemelidir?

Barış eğitimi, tarih, edebiyat vb. dersler aracılığıyla desteklenmelidir. Bu bağlamda tarih eğitimi değişik şekillerde barış eğitimini destekleyebilir. Tarih derslerinde öğrenciler geçmişte barış ve barışla ilgili yapılanlar konusunda bilgilendirilmelidirler. Örnek olarak, geçmişte insanların çatışmayla karşılaştıkları zaman barışı nasıl tercih ettikleri; barış kültürünün nasıl inşa edildiği; farklı din, kültür ve etnik yapıya sahip olan insanların beraber nasıl yaşadıkları; çatışma ve anlaşmazlıkları çözmek için barış antlaşmalarının ve girişimlerinin ne kadar önemli olduğu tarih derslerinde belirtilmelidir.

Bunun yanı sıra, tarih dersleri, barış konusundaki kavramları öğretme fırsatı sunabilir; çünkü tarih okullarda okutulan bir ders olarak mevcut sorunları anlamada yardımcı olabilecek birçok kavrama sahiptir ve bu kavramların bazıları barış ve barış eğitimi ile ilgilidir. Bu kavramlar arasında hoşgörü, diyalog, müzakere, uzlaşma, barışma, şiddet içermeyen mücadele, sosyal adalet, özgürlük, insan hakları, savaş ve savaş suçları yer almaktadır. Tarih dersleri, öğrencilerin geçmişten günümüze bu kavramları tarihsel bir perspektiften anlamalarına yardımcı olur. Bunun yanında tarih dersleriyle öğrenciler aşağıdaki barış eğitimiyle ilgili nitelikleri de geliştirebilirler.

– Barışı korumanın, barışın sağlanmasının ve barışın geliştirilmesinin öneminin farkına varma.

– Çatışmaları kuvvet kullanmadan çözmenin öneminin farkına varma.

– Sürdürülebilir bir gelecek için barış ve barışın geliştirilmesinin öneminin farkına varma.

– Şiddetin ve geçmişten günümüze yapılan savaşların farkına varma.[4]

Öğrenciler tarih derslerinde barışın önemini öğrenebilirler. Bu çerçevede tarih öğretmenleri yukarıdaki kavramlarla ilgili örnek olaylar ve kanıtlar eşliğinde aktif öğretim etkinlikleri geliştirmelidirler. Özellikle barış eğitimi, hoşgörü ve insan haklarıyla ilgili yazılı metinler barışla ilgili bakış açısını geliştirmek için tarih derslerinde kullanılabilir.

Türk Tarih Öğretim Programında Barış Eğitimi

2000’li yılların başında küreselleşme, uluslararası gelişmeler ve Avrupa Birliği’ne üyelik müzakere süreci nedeniyle Türkiye’de tarih öğretim programlarında bir yenilenme süreci yaşandı.[5] Tarih öğretim programı, yapılandırmacı öğretim yaklaşımı ışığında yeniden şekillendirildi. Bu dönemde barış, insan hakları ve hoşgörü gibi kavramlar Avrupa ülkelerinin tarih öğretim programlarında dikkat çekmekteydi ve bu kavramlar belli ölçüde Türk Tarih Öğretim Programları’nda yerini aldı. Örneğin, tarih öğretim programının genel amaçlarından birisi, öğrencilerin barış, hoşgörü, karşılıklı anlayış, demokrasi ve insan haklarının önemini anlaması ve bu konulara duyarlı olmalarının öğretilmesidir.

Bunun yanı sıra, 9. Sınıf Tarih Öğretim Programı kazanımlarından birisi, farklı kültürlerden, görüşlerden ve inançlardan insanlara hoşgörü ve saygı göstermektir.[6] Ayrıca, 10. Sınıf Tarih Öğretim Programı, tarih öğretmenlerinin Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun hoşgörüsünü, özellikle de Balkanlardaki vergi adaletini ve hoşgörüsünü vurgulamalarını öğretmenlerden beklemektedir.[7] Buna ek olarak, Kemal Atatürk’ün sloganı olan “Yurtta Barış ve Dünyada Barış” 12. Sınıf Tarih Öğretim Programı’nda vurgulanmıştır.[8] Öğretim programlarında barış eğitimiyle ilgili kavramlara belli oranda yer verilmişse de tarih derslerinin barış eğitimini yeterli düzeyde desteklemediği söylenebilir.

Osmanlı Arşiv Metinlerinin Barış Eğitiminde Kullanımı

Osmanlı İmparatorluğu (1299-1923) resmi kayıt tutmanın öneminin farkında bir devletti ve bu kayıtların bir kısmı 1984’ten beri İstanbul’da araştırmacılara açıktır.[9] Osmanlı Arşivi’nde Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun sosyal, siyasi, diplomatik, askeri ve ekonomik tarihi hakkında milyonlarca metin bulunmaktadır. Bu metinler aynı zamanda, toprakları Afrika, Balkanlar, Ortadoğu, Kafkaslar, Kıbrıs ve hatta İsrail gibi Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun bir parçası olan ülkeler hakkında önemli bilgiler vermektedir.

Osmanlı İmparatorluğu, farklı etnik kökenleri ve dinleri içeren geniş bir coğrafi alanı kontrol altına almış ve gayrimüslimlerin bazı haklarını garanti altına almıştır; bu haklar yazılı olarak kaydedilmiş ve kayıtlar Osmanlı Arşivi’nde tutulmuştur. Bu kayıtlar ve metinler sadece tarihsel kanıt değil, aynı zamanda tarih derslerinde barış ve hoşgörü eğitimini destekleyen pedagojik araçlar olarak da kullanılabilir. Bunlardan birisi, Bosna’nın Osmanlı İmparatorluğu tarafından fethinden sonra 1463’te Bosna rahiplerine verilen haklarla ilgilidir. İstanbul fatihi Sultan II. Mehmed (1432-1481) 1463 yılında yayınlanan bir fermanla Bosnalı rahiplere aşağıdaki hakları verdi:

– Bosnalı rahipler özgürlük ve korumaya sahip olacaklardır.

– Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’ndaki manastırlarına ve topraklara geri dönüp endişesiz yerleşebilirler.

– Hiç kimse onlara saldırmayacak; yaşamlarını, mallarını veya kiliselerini tehdit etmeyecektir.[10]

Bu fermanın metni tarih derslerinde barış ve hoşgörü eğitimi açısından değerlendirilebilir. Bu amaçla öğrenciler tarihsel metinleri değerlendirmek için çalışma yapraklarını kullanabilirler. Yukarıdaki ferman metnini değerlendirirken aşağıdaki sorular sorulabilir:

– Ferman ne zaman basıldı?

– Ferman yayınlandığında insan haklarının durumu neydi?

– Fermanı insan hakları açısından nasıl değerlendirebilirsiniz?

– O zamanlarda yaşıyor olsaydınız, gayrimüslimler için böyle haklar verir miydiniz?

– Farklı inanç, din ve etnisiteye sahip insanlara haklar verilmesi barışı nasıl destekler?

– 1463’te Bosna rahiplerine verilen hakları İnsan Hakları Evrensel Beyannamesi ile karşılaştırınız.

– Fermanla ilgili görüşlerinizi insan hakları ve hoşgörü açısından yazınız.

Özetle, öğrencilere tarih derslerinde barış eğitimiyle ilgili gerekli olan bilgi, beceri ve tutumlar kazandırılmalıdır; çünkü tarih dersleri farklı din, dil ve kültüre sahip insanların barış içinde geçmişte nasıl yaşadığını bize göstermektedir. Özellikle barış ve hoşgörüye ilişkin birinci elden kanıtlar öğrenciler tarafından aktif öğrenme ışığında değerlendirilmelidir.

_____________________

Tavsiye edilen okuma metinleri

- Aktaş, Özgür ve Safran, Mustafa. Evrensel Bir Değer Olarak Barış ve Eğitiminin Tarihçesi. Türkiye Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, 17/2 (2013), ss. 131-15.

- Demircioğlu, İsmail H. Using Historical Stories to Teach Tolerance: The Experiences of Turkish Eighth-Grade Students. The Social Studies 93/3 (2008), pp. 105-110.

- Deveci, H., Yılmaz, F. and Karadağ, R. Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions of Peace Education. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 30 (2008), pp. 63.

İnternet siteleri

- General Directorate of State Archives of the Prime Ministry of the Republic of Turkey. http://en.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/ (Erişim tarihi: 6 Şubat 2017).

_____________________

[1] “Peacebuilding and peace education,” Insight on Conflict , https://www.insightonconflict.org/themes/peace-education/ (Erişim tarihi: 1 Ocak 2017).

[2] Ian Harris, “History of Peace Education,” in Encyclopedia of Peace Education , Monisha Bajaj (Yay.), (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2008), 15-24.

[3] John W. Collins/Nancy Patricia O’Brien, The Greenwood Dictionary of Education (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2011).

[4] Ian Harris ve Mary Lee Morrison, Peace Education (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2003).

[5] İsmail H. Demircioğlu, “Being A History Teacher in Turkey,” Public History Weekly 4/35 (2016), https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/4-2016-35/being-a-history-teacher-in-turkey/ (Erişim tarihi: 9 Ocak 2017).

[6] T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanliği, “Tarih Dersi Öğretim Programi (9. Sinif)” (Ankara 2007), http://ogm.meb.gov.tr/belgeler/tarih9.pdf (Erişim tarihi: 9 Ocak 2017).

[7] T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanliği, “Ortaöğretim 10. Sinif Tarih Dersi Programi” (Ankara 2008), http://etarih.com/tarih/mufredat/Programlar/tarih_10.pdf (Erişim tarihi: 9 Ocak 2017).

[8] T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanliği, “Ortaöğretim Çağdaş Türk Ve Dünya Tarihi Dersi Öğretim Programi” (Ankara 2008), http://ogm.meb.gov.tr/belgeler/cagdas_turkdunyatarih.pdf (Erişim tarihi: 9 Ocak 2017).

[9] T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü, http://en.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/icerik/236/devlet-arsivleri-genel-mudurlugu-tarihcesi/ (Erişim tarihi: 9 Ocak 2017).

[10] Mitja Velikonja, Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina (College Station, TX: Texas University Press, 2003); Cevat Ekici, Living Together Under the Same Sky (Ankara: T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü, 2006).

_____________________

Image Credits

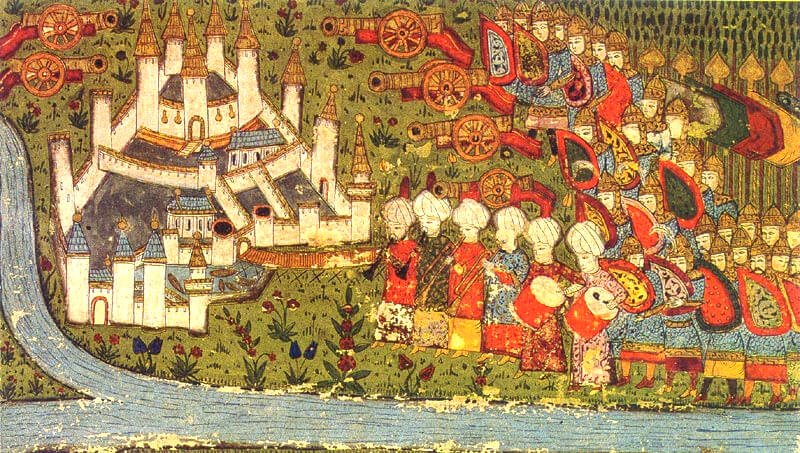

Ottoman miniature of the siege of Belgrade by Mehmed II in 1456. Photo by WikipediaUser “Dencey”, 2017 © Public Domain, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehmed_II.#/media/File:Siegebelgrade.jpg (accessed February 7, 2017).

Recommended Citation

Demircioğlu, İsmail H.: Osmanli Arşiv Belgelerinin Bariş Eğitiminde Kullanilmasi. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8374

Since the dawn of the new millennium, humanity has been confronted with many problems. These include starvation, poverty, racism, ethnic hatred, wars, terrorism, genocide, environmental pollution, illegal immigration, violence, street crimes and intolerance. In order to solve these issues, education can play an important role; it can also render our world both pleasanter and kinder. Moreover, education can help students to develop skills for practical thinking, problem solving and co-operating with each other. Besides encouraging creativity, innovation and communication, peace education can drive students towards a more conscientious, tolerant, peaceful and democratic way of thinking.

What is Peace Education?

Peace education concerns the development of knowledge, skills and attitudes in order to prevent the occurrence of conflicts, to resolve them peacefully and to create social conditions which allow peace to endure.[1] Alternatively, peace education can be defined as the teaching of peace, its aim being to stimulate a resolve to commit to the ways of peace.[2] It should also develop a desire within people to live in peace and to emphasize peaceful values upon which society should be based.[3]

Does History Teaching Support Peace Education?

Peace education in school can and should be combined with other disciplines such as history and literature. The teaching of history can contribute to peace education in different ways. For example, students can be given information about peace-related themes and peace activities which occurred in the past. Possible topics include peace initiatives, peace agreements and examples of peaceful cultures as well as the harmonious co-existence of groups belonging to different religions, cultures and ethnic backgrounds.

Furthermore, history lessons can provide an opportunity for familiarizing students with issues related to peace education such as tolerance, dialogue, negotiation, reconciliation, non-violence, social justice, freedom, human rights, war and war crimes. History lessons can help students to understand these concepts by using a historical perspective. In addition to what has already been mentioned, the teaching of history can also encourage students to recognize:

– the importance of peacemaking, peacebuilding and peacekeeping;

– the importance of solving conflicts without the using of force;

– the importance of peace for a sustainable future;

– and the sorrow caused by violence and wars from the past to the present.[4]

History teachers can draw upon case studies and historical evidence related to the above concepts in order to teach them in a pragmatic way. For example, the examination and evaluation of written material allows students to develop an insight into peace, tolerance and human rights.

Peace Education in the Turkish History Curriculum

In the wake of globalization, international developments and the EU membership negotiation process, the first decade of the twenty-first century was subject to major reforms in the Turkish school curricula.[5] The history curriculum was reshaped according to the constructivist approach of teaching. Concepts such as peace, tolerance and human rights, long established in the history curricula of European countries, are now present in the Turkish history curriculum to some extent. For example, one of the general objectives of teaching history now stipulates that students should understand the importance of peace, tolerance, mutual understanding, democracy and human rights. At the same time, education should encourage them to protect and develop these values.

In addition to this, the history curriculum for the ninth grade explicitly emphasizes that the process of learning history should promote respect for (and tolerance of) people with different cultural backgrounds, opinions and beliefs.[6] The curriculum for the tenth grade requires history teachers to stress the tolerant attitudes of the Ottoman Empire regarding tax collection and their policies in the Balkans.[7] In the curriculum for the twelfth grade, peace education is addressed by using Kemal Atatürk’s policy of “Peace at Home, Peace in the World”. Despite the examples given, it can be said that history lessons in Turkey still fail to adequately support peace education.[8]

Texts from Ottoman Archives for Peace Education

The Ottoman Empire (1299–1923) has bequeathed to us a vast amount of official records, some of which have been available for research in Istanbul since 1984.[9] The collection consists of millions of documents which deal with social, political, diplomatic, military and economic matters of the Ottoman Empire. They also contain valuable information on the Balkan states, the Middle East, the Caucasus, Africa, Cyprus and even Israel—territories which used to be part of the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman Empire covered a wide geographical area which comprised many different ethnicities and religions. During their rule, the Ottomans granted a number of rights to non-Muslims, as records kept in the Ottoman archives indicate. These records can be used not only as historical sources, but also as pedagogical tools for history lessons as some of them lend themselves very well for the purposes of peace education. A case in point is a text documenting the rights given to Bosnian priests after the conquest of Bosnia by the Ottomans in the fifteenth century. In an edict issued in 1463, Sultan Mehmed II (1432–1481), the conqueror of Istanbul, bestowed the following rights upon Bosnian priests:

– The Bosnian priests were to have their freedom granted and protection given to them.

– They were to be allowed to return to and settle in their monasteries in the lands belonging to the [Ottoman] empire—without any reservations.

– Nobody was to harm them, nor threaten their lives, property or churches.[10]

In history lessons, the edict can be evaluated in terms of its meaning for peace and tolerance education by using a worksheet, for example. In order to assess the text, students could be asked the following questions:

– When was the edict issued?

– Which situation is being described in the edict?

– How would you evaluate the edict in terms of its relation to human rights?

– Would you have granted such rights to non-Muslims if you had lived at that time?

– How does bestowing rights upon people with different beliefs, religions and ethnic backgrounds support peace?

– How do the rights given to Bosnian priests in 1463 compare to those provided by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948?

– How would you sum up your views about the edict in terms of human rights and tolerance?

In conclusion, it may be suggested that students should be given the opportunity in history lessons to acquire and develop knowledge, skills and attitudes with regards to peace education. This is due to the fact that history can show us how people with different beliefs, religions, cultures and ethnic backgrounds have been able to live in peace together. In particular, primary sources which emphasize the values of peace and tolerance should be evaluated by students as part of active learning.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Aktaş, Özgür ve Safran, Mustafa. “Evrensel Bir Değer Olarak Barış ve Eğitiminin Tarihçesi.” Türkiye Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, 17/2 (2013): 131-15.

- Demircioğlu, İsmail H. “Using Historical Stories to Teach Tolerance: The Experiences of Turkish Eighth-Grade Students.” The Social Studies 93/3 (2008): 105-110.

- Deveci, H., Yılmaz, F. and Karadağ, R. “Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions of Peace Education.” Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 30 (2008): 63.

Web Resources

- General Directorate of State Archives of the Prime Ministry of the Republic of Turkey. http://en.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/ (last accessed 6 February 2017).

_____________________

[1] “Peacebuilding and peace education,” in Insight on Conflict , https://www.insightonconflict.org/themes/peace-education/ (last accessed 1 January 2017).

[2] Ian Harris, “History of Peace Education,” in Encyclopedia of Peace Education , ed. Monisha Bajaj (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2008), 15-24.

[3] John W. Collins and Nancy Patricia O’Brien, The Greenwood Dictionary of Education , 2nd ed. (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2011).

[4] Ian Harris and Mary Lee Morrison, Peace Education (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2003).

[5] İsmail H. Demircioğlu, “Being A History Teacher in Turkey,” Public History Weekly 4/35 (2016) , https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/4-2016-35/being-a-history-teacher-in-turkey/ (last accessed 9 January 2017).

[6] Turkish Ministry of Education, “History Curriculum for the Ninth Grade” (Ankara 2007), http://ogm.meb.gov.tr/belgeler/tarih9.pdf (last accessed 9 January 2017).

[7] Turkish Ministry of Education, “History Curriculum for the Tenth Grade” (Ankara 2008), http://etarih.com/tarih/mufredat/Programlar/tarih_10.pdf (last accessed 9 January 2017).

[8] Turkish Ministry of Education, “History Curriculum for the Twelfth Grade” (Ankara 2008), http://ogm.meb.gov.tr/belgeler/cagdas_turkdunyatarih.pdf (last accessed 9 January 2017).

[9] General Directorate of State Archives of the Prime Ministry of the Republic of Turkey, http://en.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/icerik/236/devlet-arsivleri-genel-mudurlugu-tarihcesi/ (last accessed 9 January 2017).

[10] Mitja Velikonja, Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina (College Station, TX: Texas University Press, 2003); Cevat Ekici, Living Together Under the Same Sky (Ankara: General Directorate of State Archives of the Prime Ministry of the Republic of Turkey, 2006).

_____________________

Image Credits

Ottoman miniature of the siege of Belgrade by Mehmed II in 1456. Photo by WikipediaUser “Dencey”, 2017 © Public Domain, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehmed_II.#/media/File:Siegebelgrade.jpg (accessed February 7, 2017).

Recommended Citation

Demircioğlu, İsmail H.: Ottoman History and Peace Education. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8374

Seit Beginn des neuen Jahrtausends wird die Menschheit mit zahlreichen Problemen konfrontiert. Hierzu zählen Hungersnöte, Armut, Rassismus, Rassenhass, Kriege, Terrorismus, Völkermord, Umweltverschmutzung, illegale Immigration, Gewalt, Straßenkriminalität und Intoleranz. Um diese Probleme zu lösen und um die Welt zu einem besseren Ort zu machen, ist das Bildungswesen wichtig. Es soll Lernende unterstützen, Fähigkeiten wie praktisches Denken, das Lösen von Problemen und das Arbeiten im Team auszubauen. Neben der Förderung von Kreativität, Innovation und Kommunikation kann auch die Friedenspädagogik den Lernenden zu einer verantwortungsbewussteren, toleranteren, friedlicheren und demokratischeren Denkweise verhelfen.

Was ist Friedenspädagogik?

Unter Friedenspädagogik ist die Entwicklung von Wissen, Kompetenzen und Einstellungen zu verstehen, die dazu beitragen, das Aufkommen von Konflikten zu verhindern, diese friedlich zu schlichten und soziale Verhältnisse zu schaffen, die den Frieden sichern.[1] Friedenspädagogik versteht sich auch als eine Lehre vom Frieden, die das Ziel verfolgt, Lernende zu einem friedvolleren Lebensstil zu animieren.[2] Außerdem soll sie den Wunsch der Menschen fördern, in Frieden zu leben, und Werte des Friedens hervorheben, auf denen die Gesellschaft beruht.[3]

Fördert Geschichtsunterricht Friedenspädagogik?

Friedenspädagogik an Schulen kann und muss mit anderen Fächern wie Geschichte und Literatur kombiniert werden. Der Geschichtsunterricht kann auf unterschiedliche Art und Weise zur Friedenspädagogik beitragen, indem er die SchülerInnen auf friedensrelevante Themen und vergangene Friedensaktivitäten hinweist. Diese Diskussionsthemen können von Friedensinitiativen, Friedensabkommen und Beispielen von friedfertigen Kulturen sowie von der harmonischen Koexistenz von Gruppen unterschiedlicher religiöser, kultureller und ethnischer Herkunft handeln. Des Weiteren bietet der Geschichtsunterricht den Lernenden eine Möglichkeit, sich mit friedenspädagogischen Themen wie Toleranz, Dialog, Verhandlung, Schlichtung, Gewaltlosigkeit, sozialer Gerechtigkeit, Freiheit, Menschenrechte, Krieg und Kriegsverbrechen zu befassen. Ein solcher Unterricht kann helfen, diese Konzepte im Rahmen der Geschichte zu verstehen. Neben den bereits angeführten Punkten kann der Geschichtsunterricht Lernende auch ermutigen,

– die Tragweite der Friedensstiftung, der Friedensbildung und der Friedenssicherung,

– die Tragweite der Konfliktbewältigung ohne Gewaltanwendung,

– die Tragweite des Friedens für eine beständige Zukunft,

– die Gefahren, die Gewalt und Krieg von der Vergangenheit bis in die Gegenwart verursacht haben, zu erkennen.[4]

Um diese Konzepte aktiv zu vermitteln, können GeschichtslehrerInnen relevante Fallstudien und historische Zeugnisse hinzuziehen. So erlauben beispielsweise die Auseinandersetzung und die Evaluierung von Textmaterial den SchülerInnen neue Einblicke in Frieden, Toleranz und Menschenrechte.

Friedenspädagogik im türkischen Curriculum

Im ersten Jahrzehnt des einundzwanzigsten Jahrhunderts und im Zuge der Globalisierung, der internationalen Entwicklungen und der Verhandlungen um den EU-Beitritt hat die Türkei ihre Schulcurricula grundlegend reformiert.[5] Das Geschichtscurriculum wurde nach konstruktivistischen Lehransätzen umgestaltet, sodass Konzepte wie Frieden, Toleranz und Menschenrechte – schon lange fixer Bestandteil im europäischen Geschichtsunterricht – nun auch in türkischen Lehrplänen vorkommen. Eines der allgemeinen Ziele des neuen Geschichtsunterrichts ist es beispielsweise, Lernende auf die Relevanz von Frieden, Toleranz, gegenseitigem Verständnis, Demokratie und Menschenrechte aufmerksam zu machen. Gleichzeitig soll Bildung die SchülerInnen ermutigen, diese Werte weiterzuentwickeln und zu schützen.

Darüber hinaus akzentuiert das Geschichtscurriculum der neunten Schulstufe Respekt und Toleranz gegenüber Menschen anderer Kulturen, Meinungen und Glaubensrichtungen als einen wichtigen Faktor des Lernprozesses.[6] Das Curriculum der zehnten Schulstufe sieht vor, dass GeschichtslehrerInnen die Toleranz des Osmanischen Reiches hinsichtlich seiner Steuer- und Balkanpolitik hervorheben.[7] In der zwölften Schulstufe soll die Friedenspädagogik anhand von Kemal Atatürks Leitmotiv “Frieden in der Heimat, Frieden in der Welt” behandelt werden. Ungeachtet dieser Beispiele scheint der türkische Geschichtsunterricht jedoch weiterhin Friedenspädagogik nicht ausreichend umzusetzen.[8]

Texte aus osmanischen Archiven zur Friedenspädagogik

Das Osmanische Reich (1299-1923) hat uns eine Fülle an offiziellen Dokumenten hinterlassen, von denen einige seit 1984 in Istanbul als Recherchematerial zur Verfügung stehen.[9] Die Sammlung besteht aus Millionen von Belegen zu sozialen, politischen, diplomatischen, militärischen und wirtschaftlichen Angelegenheiten des Osmanischen Reiches. Sie beinhalten auch wertvolle Informationen zu den Balkanstaaten, dem Nahen Osten, dem Kaukasus, Afrika, Zypern und sogar Israel – Gebiete, die früher Teil des Osmanischen Reiches waren.

Das Osmanische Reich umfasste eine große geographische Fläche und war damit Heimat für viele Menschen unterschiedlicher Ethnizität und Religion. Während ihrer Herrschaft gewährten die Osmanen Nicht-Muslimen zahlreiche Rechte, wie Dokumente aus den osmanischen Archiven belegen. Diese Zeugnisse können nicht nur als historische Quellen, sondern auch als pädagogische Instrumente im Geschichtsunterricht herangezogen werden, da sich einige davon optimal für die Friedenspädagogik eignen. Als Paradebeispiel bietet sich ein Text an, der die Rechte bosnischer Priester nach der Unterwerfung Bosniens durch die Osmanen im fünfzehnten Jahrhundert dokumentiert. In einem Edikt von 1463 verlieh Sultan Mehmed II. (1432-1481), der Eroberer Istanbuls, bosnischen Priestern folgende Rechte:

– Bosnischen Priestern wurde Freiheit gewährt und Schutz angeboten.

– Ihnen wurde es erlaubt, ohne Einschränkung in ihre Klöster zurückzukehren, die sich nun auf [osmanischem] Boden befanden.

– Niemand durfte ihnen Schaden zufügen, noch ihr Leben, Eigentum oder Kirche bedrohen.[10]

Im Geschichtsunterricht kann das Edikt zum Beispiel durch ein Arbeitsblatt in Bezug auf die Friedens- und die Toleranzpädagogik beurteilt werden. Um den Text zu verstehen, können den SchülerInnen folgende Fragen gestellt werden:

– Auf wann lässt sich das Edikt datieren?

– Welche Situation wird im Edikt beschrieben?

– Wie würdet ihr das Edikt in Bezug auf die Menschenrechte beurteilen?

– Hättet ihr Nicht-Muslimen die gleichen Rechte eingestanden, wenn ihr zu dieser Zeit gelebt hättet?

– Inwieweit wird Frieden unterstützt, wenn Rechte an Menschen mit unterschiedlicher Meinung, Religion und ethnischer Herkunft verliehen werden?

– Inwieweit lassen sich die Rechte für bosnische Priester von 1463 mit jenen der Allgemeinen Erklärung der Menschenrechte von 1948 vergleichen?

– Wie würdet ihr eure Gedanken zum Edikt in Bezug auf die Menschenrechte und Toleranz zusammenfassen?

Abschließend sei gesagt, dass den Lernenden eine Möglichkeit gegeben werden soll, im Geschichtsunterricht Wissen, Kompetenzen und Einstellungen mit friedenspädagogischem Ansatz zu erwerben und zu entwickeln. Dies lässt sich mit dem Umstand erklären, dass Gesichten uns zeigen kann, wie Menschen mit unterschiedlichen Glaubenssätze, Religionszugehörigkeiten, kulturellem und ethnischen Hintergrund friedlich zusammenzuleben vermochten. Im Besonderen sollen Quellen, die Werte wie Frieden und Toleranz vermitteln, von SchülerInnen durch aktives Lernen erarbeitet und beurteilt werden.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Özgür Aktaş / Mustafa Safran: Evrensel Bir Değer Olarak Barış ve Eğitiminin Tarihçesi. In: Türkiye Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 17 (2013), H. 2, S. 131-15.

- İsmail H. Demircioğlu: Using Historical Stories to Teach Tolerance: The Experiences of Turkish Eighth-Grade Students. In: The Social Studies 93 (2008), H. 3, S. 105-110.

- Handan Deveci / Fatih Yılmaz / Ruhan Karadağ: Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions of Peace Education. In: Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 30 (2008), S. 63.

Webressourcen

- General Directorate of State Archives of the Prime Ministry of the Republic of Turkey. http://en.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/ (letzter Zugriff 06.02.2017).

_____________________

[1] Peacebuilding and peace education, auf Insight on Conflict: https://www.insightonconflict.org/themes/peace-education/ (letzter Zugriff 01.01.2017).

[2] Ian Harris: History of Peace Education. In: Monisha Bajaj (Hrsg.): Encyclopedia of Peace Education. Charlotte 2008, S. 15-24.

[3] John W. Collins/Nancy Patricia O’Brien: The Greenwood Dictionary of Education. Santa Barbara 2011.

[4] Ian Harris/Mary Lee Morrison: Peace Education. Jefferson 2003.

[5] İsmail H. Demircioğlu: Being A History Teacher in Turkey. In: Public History Weekly 4/35 (2016). https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/4-2016-35/being-a-history-teacher-in-turkey/ (letzter Zugriff 09.01.2017).

[6] Türkisches Bildungsministerium: Geschichtslehrplan für die neunte Schulstufe (Ankara 2007), http://ogm.meb.gov.tr/belgeler/tarih9.pdf (letzter Zugriff 09.01.2017).

[7] Türkisches Bildungsministerium: Geschichtslehrplan für die zehnte Schulstufe (Ankara 2008), http://etarih.com/tarih/mufredat/Programlar/tarih_10.pdf (letzter Zugriff 09.01.2017).

[8] Türkisches Bildungsministerium: Geschichtslehrplan für die zwölfte Schulstufe (Ankara 2008), http://ogm.meb.gov.tr/belgeler/cagdas_turkdunyatarih.pdf (letzter Zugriff 09.01.2017).

[9] General Directorate of State Archives of the Prime Ministry of the Republic of Turkey: http://en.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/icerik/236/devlet-arsivleri-genel-mudurlugu-tarihcesi/ (letzter Zugriff 09.01.2017).

[10] Mitja Velikonja: Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station, TX 2003. Cevat Ekici: Living Together Under the Same Sky. Ankara 2006.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Osmanische Miniatur der Belagerung Belgrads durch Mehmed II. im Jahr 1456. Foto von WikipediaUser “Dencey”, 2017 © Public Domain, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehmed_II.#/media/File:Siegebelgrade.jpg (letzter Zugriff am 7.2.2017).

Übersetzung

Stefanie Svacina and Paul Jones (paul.stefanie [at] outlook.at)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Demircioğlu, İsmail H.: Osmanische Geschichte und Friedenspädagogik. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8374

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 6

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8374

Tags: Language: Turkish, Ottoman Empire (Osmanisches Reich), Peace education (Friedenspädagogik), Turkey (Türkei)

As a teacher, I am aware of the fact that students are being affected by curriculums and textbooks. If textbooks and curriculum were designed with the purpose of fostering peace and tolerance, then the world would be a more liveable place. We have to look at historical events illustrating how people used to live together in peace in the past in order to create a history curriculum that fosters peace and tolerance in schools. We know that people of different ethnicity, religion and culture used to live together peacefully in the Ottoman period and that the sultans granted basic rights to those citizens who were non-Muslim, and they enjoyed a high degree of autonomy within their own community in terms of religion and culture. The rights of non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire were secured by the decrees of the sultans. As mentioned in the paper, the Bosnian priests were granted important right by the Sultan in 1463 and these rights can be considered progressive for 15th century. I am sure that there exist more papers dealing with the rights of non-Muslims in the archives of the Ottoman Empire and they should be made use of in history lessons in order to promote peace and tolerance in education.

History teaching mostly focuses on past conflicts and wars. As of in media unlike bad news, good news barely becomes headline. Young generations assume that history is full of tyranny, cruelty, brutality, colonization, murder, war etc. Reading history textbooks carries these past conflicts to present times.

However, as Demircioğlu stated in this work, history also shows us good “examples of peaceful cultures as well as the harmonious co-existence of groups belonging to different religions, cultures and ethnic backgrounds.”

If history can change its focus from conflicts to peace, we can create a better world for coming generations and Demircioğlu’s work supplies us a good example of peace education through history teaching.

Eine deutschsprachige Version siehe unten.

Contributing to counter-enlightenment

One may ask, why Ottoman edicts, which were co-constitutive for founding the Millet-system, are debated in the Turkish history curriculum as predecessor of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

One possible answer suggests itself: The Ottoman Empire is a part of Turkish history. It is a part of the history of the Balkans and other regions in which the Millet-system was implemented. This history is remembered in various locations very differently—that might be regarded as one of the outcomes of the Millet-system. The Millet-system can be regarded as an answer to the administrative needs of an early modern empire. As such a system, it was not created on the desk of one single scholar, but resulted form a complex historical process—namely the expansion of the empire into non-Muslim areas. Some remember this process as a series of military campaigns. The picture illustrating the initial contribution suggests that reading as well.

As a result of their campaigns the conquerors were confronted with a number of tasks regarding peace education. For example the consent and the governability of the subjects had to be ensured. Therefore, the Millet-system provided the different religious communities the right to deal autonomously with the legal affairs of their own community—the Millet—i.e. they had their jurisdiction. That provided many benefits for the new administrators, particularly in areas with a large share of non-Muslim population. Nevertheless within the Millet-system the Millets were not equal. Non-Muslims were not on par with Muslims. This became particularly evident when juridical cases between the individuals of different Millets occurred. In its core the Millet-system denied the principle of equality among all subjects of the Sultan. Furthermore, there were relations between the Sultan and the population only by the intermediation of the religious leaderships of the Millets.

The Feudal orders in Europe also did not know the principle of legal equality, their legal orders were rankly. The principle of legal equality was pushed against the Feudal orders within a long process of enlightenment. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights which codifies the freedom and equality of all individuals can be regarded as a historical answer toward all legal orders, which do not know or actively deny that principle. It has several pitfalls to search in the Ottoman history for predecessors of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But who is willing to accept those pitfalls, may find in the reforms of the Tanzimat (19th century) such a predecessor. Contrary to those Sultanic edicts which are constitutive for a system codified inequality, the Tanzimat reforms contained at least the pursuit to create legal equality among the subjects of the Sultan.

Nobody should exaggerate the process of enlightenment, or regard our nowadays world as the complete realisation of the promises of freedom and equality. There has been pronounced particularism – particularly in the context of the European colonisation of the world. And particularism still prevails. Unfortunately, to the heritage of enlightenment belongs as well the fact, that new forms of inequality are processed on the shoulders of formal equality.

Nevertheless, enlightenment immanently calls to realise its promises—that enables us to criticise their non-realisation. If the recourse on Sultanic edicts, which do not formulate such a promise, provides an adequate opportunity to debate the promises of freedom and human rights, is to be questioned. Rather there is reason to fear, that the curriculum contributes toward a reception, which degrades promises of freedom and human rights under the principle of tolerance.

Tolerance is not a fundamental right, because its provision lies in the hands of the stronger. In this sense the Turkish curriculum contributes toward counter-enlightenment. This manifests itself not least in the fact that such edicts are not primarily put as historical sources into their context, but are used as pedagogical instruments. Particularly under consideration of the specific questions provided in the didactical materials, it is to be feared, that their pedagogical use contributes toward the relativisation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights from 1948.

We may close with their second article:

—————————————-

Ein Beitrag zur Gegenaufklärung

Es ist zu fragen, warum ausgerechnet osmanische Edikte, die das Millet-System mitbegründen, im türkischen Geschichtscurriculum als Vorläufer der Allgemeinen Deklaration der Menschenrechte debattiert werden?

Eine mögliche Antwort liegt nahe: Das Osmanische Reich ist Teil türkischer Geschichte. Es ist Teil der Geschichte des Balkans und weiterer Regionen in denen das Millet-System implementiert wurde. Dieser Geschichte wird an verschiedenen Orten sehr unterschiedlich erinnert – auch das ist ein Ergebnis des Millet-Systems. Das Millet-System bildet eine Antwort auf die Verwaltungserfordernisse des frühneuzeitlichen Großreiches und ist als solches System nicht in der Schreiberstube eines einzelnen Rechtsgelehrten entstanden, sondern in einem komplexen historischen Prozess der Ausdehnung des Reiches in nicht-muslimische Gebiete hineinen. Manche erinnern diesen Prozess als eine Serie von Feldzügen. Auch die Bebilderung des Artikels legt dies nahe.

Die Eroberer waren im Ergebnis ihrer Feldzüge mit einer Reihe friedenspädagogischer Aufgaben konfrontiert. Zum Beispiel sollten die Zustimmung und Regierbarkeit der neuen Untertanen sichergestellt werden. Dazu ermöglichte das Millet-System den verscheidenen religiösen Gemeinschaften die rechtlichen Fragen innerhalb ihrer eigenen Gemeinschaft, dem Millet, autonom zu regeln, sie hatten also eine eigene Juristtriktion. Gerade in Gebieten mit großem nicht-muslimischen Bevölkerungsanteil war das vorteilhaft für die neuen osmanischen Verwalter.

Allerdings gab es im Millet-System keine Gleichstellung der einzelnen Millets. Nicht-Muslime waren Muslimen juristisch nicht ebenbürtig. Dies zeigte sich insbesondere, wenn es zu Streitfällen zwischen den Individuen verschiedener Millets kam. Im Kern lehnte das Millet-System das Prinzip der Rechtsgleichheit aller Untertanen des Sultans ab. Es stellte darüberhinaus die Beziehungen zwischen Sultan und Bevölkerung nur über die religiös-geistlichen Führungen der Millets her.

Auch die europäischen Feudalordnungen kannten kein Prinzip der Rechtsgleichheit aller Untertanen, die Ordnungen waren ständisch. Es wurde erst im langen Prozess der Aufklärung im Kampf gegen die Feudalordnungen durchgesetzt. Die Allgemeine Erklärung der Menschrechte, die die Freiheit und Gleichheit aller Individuen kodifiziert stellt in gewisser Weise eine historische Antwort auf alle Rechtsordnungen dar, die dieses Prinzip nicht kennen oder aktiv ablehnen. Es ist mit vielen Fallstricken behaftet in der osmanischen Geschichte nach Vorläufern zur Allgemeinen Erklärung der Menschrechte zu suchen. Doch wer diese in Kauf nimmt, mag in den Reformen des Tanzimats (19. Jahrhundert) einen solchen Vorläufer erblicken. Im Gegensatz zu jenen sultanischen Edikten, die konstitutiv für ein System kodifizierter Ungleichheit sind, wohnte ihnen zumindest das Bestrebten inne Rechtsgleichheit zwischen den Untertanen herzustellen.

Niemand sollte den Prozess der Aufklärung überhöhen oder unsere heutige Welt als reale und vollständige Einlösung der Versprechen von Freiheit und Gleichheit zu betrachten. Es herrschte und herrscht ein ausgeprägter Partikularismus – gerade im Kontext der europäischen Kolonisierung der Welt. Auch das Faktum, das neue Formen der Ungleichheit auf den Schultern formaler rechtlicher Gleichheit prozessiert werden, zählt leider zum Erbe der Aufklärung. Allerdings ermöglicht letztere uns die Kritik an der Nichteinlösung dieser Versprechen, sind sie ihr doch immanent. Ob aber der Rückgriff auf Edikte, die dieses Versprechen gar nicht erst formulieren, eine adäquate Thematisierung von Freiheits- und Menschenrechtsversprechen ermöglicht, ist zu bezweifeln. Es steht zu befürchten, dass das Curriculum einen Beitrag zu einer Rezeption leistet, die Freiheit und Gleichheit dem Prinzip der Toleranz unterordnet.

Toleranz ist kein Grundrecht, denn deren Gewährung liegt immer in der Hand des Stärkeren. In diesem Sinne leistet das türkische Geschichtscurriculum einen Beitrag zur Gegenaufklärung. Dies manifestiert sich nicht zuletzt darin, derartige Edikte nicht etwa als historische Quellen zu kontextualisieren, sondern sie als pädagogische Instrumente einzusetzen. Insbesondere unter Beachtung der spezifischen Fragestellung der Unterrichtsmaterialen, steht zu befürchten, dass dieser pädagogische Einsatz einen Beitrag zur Relativierung der Allgemeinen Erklärung der Menschenrechte von 1948 leistet.

Schauen wir uns abschließend deren Zweiten Artikel an: