Abstract: “Our difficulty in forming an opinion is much bigger than yours: We have to see everything that the media tells us, go through a process of understanding, of selecting, so we can see what we’re going to be in favor of – what we’re going to be against […].”[1] – Ana Júlia, Brazilian, sixteen-year-old high school student.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8254.

Languages: Português, English, Deutsch

“A nossa dificuldade de poder formar um pensamento é muito maior do que a de vocês: nós temos que ver tudo o que a mídia nos passa, fazer um processo de compreensão, de seleção, pra daí a gente conseguir ver do que a gente vai ser a favor, do que a gente vai ser contra […].”[1] – Ana Júlia, estudante secundarista brasileira, 16 anos.

O que faz o mundo mudar?

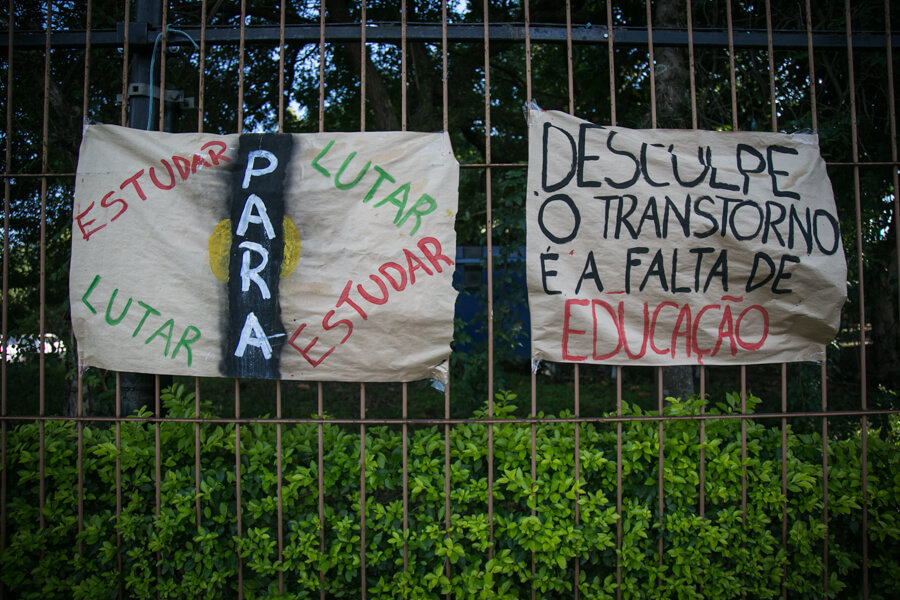

As manifestações de rua e os movimentos de ocupações de escolas e universidades tem movimentado o cenário político brasileiro pelo menos desde julho de 2013. Tradicionalmente, a juventude é vista como a encarnação do novo e da mudança. Entretanto, uma curta frase do discurso da jovem Ana Júlia demonstra a relevância do diálogo a ser construído na escola e no ensino de história, pois todos – professores e estudantes – precisamos de tempo e de diálogo para entender o que acontece e se posicionar no mundo.

Pensando nisso, exploramos aqui uma possibilidade de análise sobre o pensamento de jovens de países do Mercosul sobre fatores de mudança para o passado e o futuro. Os dados foram coletados pelo projeto de pesquisa Jovens & História, da qual participaram cerca de 3800 estudantes de 15 anos de todo o Brasil, da Argentina, do Uruguai e do Chile.[2] Os jovens foram convidados a avaliar que influência tiveram alguns fatores na mudança da vida das pessoas desde 1970 até hoje e que influência terão de agora até 2050. Cada fator deveria ser avaliado numa escala entre Muito Pouca, Pouca, Média, Grande e Muito Grande influência. As mesmas opções existiam para as questões sobre o passado e sobre o futuro.[3]

A intenção foi verificar quais foram as razões mais recorrentes evocadas para explicar as mudanças do passado e do futuro, se há diferenças entre os jovens de diferentes países, refletir que narrativas de passado (causalidades) e expectativas de futuro podem ser inferidas e se as razões mais e menos recorrentes oferecem indícios sobre a visão desses jovens sobre seu papel como agentes da história.

Estudantes e Fatores de mudança

Entre os estudantes, os fatores de mudança mais recorrentes de 1970 até hoje, na contagem geral, são: Desenvolvimento da ciência e do conhecimento; Invenções técnicas e mecanização; Interesses econômicos e concorrência econômica; Cientistas e engenheiros; Movimentos e conflitos sociais. Os menos recorrentes são: Fundadores de religiões e chefes religiosos; Filósofos, pensadores e pessoas instruídas; Esforço pessoal; Migrações e a Organização dos trabalhadores. Em um lugar intermediário estão Reis, presidentes e personagens politicamente importantes no poder; Revoluções políticas; Questões ambientais e Guerras e conflitos junto com Reformas políticas.

Com relação aos fatores de mudança para o futuro, os estudantes permanecem basicamente com as mesmas perspectivas, com a diferença de que as questões ambientais tornam-se bem mais prementes. Além disso, atesta-se a avaliação negativa, na média geral, atribuídos aos fundadores de religiões e chefes religiosos e aos Filósofos, pensadores e pessoas instruídas. É tentador questionar se após a intensa divulgação da crise de refugiados na Europa e a intensificação de atos de grupos baseados em fundamentalismo religioso os estudantes seguiriam valorizando da mesma forma o poder das religiões e das migrações como fatores de mudança.

Ao comparar as respostas dos estudantes dos quatro países, nota-se que Chile e Uruguai se destacam dos demais. Brasil e Argentina permanecem mais próximos à média geral, sendo os argentinos os estudantes com números mais pessimistas que os demais, principalmente sobre fatores de tipo individual. Os estudantes chilenos estão bem acima da média geral nos fatores Movimentos e conflitos sociais; Reis, presidentes e personagens politicamente importantes no poder; Reformas políticas; Guerras e conflitos; Filósofos, pensadores e pessoas instruídas; Revoluções políticas; Migrações e Organização dos trabalhadores. Isso pode significar que os estudantes chilenos e, em alguma medida, também os uruguaios, estão mais afastados de um posicionamento neutro do que os demais, o que não se reflete nas projeções de futuro, em que permanecem próximos à média.

Fatores além do controle

O panorama reflete a ideia de que as inovações no campo da tecnologia e das invenções, junto com interesses econômicos e conflitos sociais foram os fatores mais relevantes de mudança, na avaliação dos estudantes. Questões individuais e coletivas encontram-se tanto entre os fatores mais relevantes quanto nos menos relevantes, embora priorizem, sem dúvida, fatores cujo controle é difícil de ser estabelecido, sendo os cientistas e engenheiros os únicos que aparecem como indivíduos relevantes, à frente dos movimentos e conflitos sociais. Temas que, atualmente, são muito relevantes no debate político mundial, como líderes religiosos e migrações, não eram vistos como relevantes quando esses jovens responderam a questão.

As respostas dadas pelos docentes participantes da mesma pesquisa foram muito semelhantes às dos jovens, o que poderia indicar que se trata de um reflexo da cultura histórica dos participantes. Mas pode ser também indícios de uma tendência presente na história escolar?

Infere-se, desses fatores, que os jovens constroem um panorama estável sobre os últimos e os próximos quarenta anos na história. Visões tradicionais sobre a história dos heróis e grandes homens não são relevantes para os jovens participantes. Por outro lado, tampouco são as revoluções populares ou movimentos de trabalhadores os motores de mudança. Parece que os fatores mais importantes são aqueles fora do controle da vida cotidiana: a tecnologia, as inovações, a engenharia e as grandes questões econômicas tem determinado o que mudou e o que vai mudar no tempo de uma geração.

Enfrentando Processos de Decisão!

Assim, poderíamos celebrar a ausência de fatores como “grandes homens” e “batalhas” entre os favoritos dos estudantes, mostrando uma vitória sobre narrativas históricas tradicionais. Ou então, lamentar que os movimentos de trabalhadores ou o esforço pessoal (segundo a inclinação de cada um) recebem pouca atenção. De qualquer forma, é pertinente interrogar sobre a forma como os jovens se veem como agentes nos processos da vida e como tomam decisões.

Sem dúvida, as intensas mobilizações dos últimos meses denotam esperança, em tempos que se anunciam sombrios. Talvez a cultura histórica que circula socialmente seja uma fonte de problematizações para a compreensão da agência histórica dos jovens, ao privilegiar tecnologia e invenções como fatores de mudança – daí a angústia de Ana Júlia perante o turbilhão de informações que não controlam. A história escolar deveria, portanto, preocupar-se mais com os fatores de mudança para o passado e para o futuro e mobilizar tais compreensões em sala de aula?

Esse breve panorama apenas reforça o constante desafio para a formação docente e também para a produção de materiais didáticos: problematizar e compreender a mudança no tempo, tendo como foco central as tomadas de decisão e a mobilização para construir o novo. Tarefa que, sabemos, não pertence apenas aos jovens.

_____________________

Leitura adicional

- Pacievitch, Caroline/Cerri, Luis Fernando. “Professores de História e sua relação com a política: uma abordagem comparativa na América do Sul.” Opsis 15 (2015): 516-536.

- Cerri, Luis Fernando/Morlar, Jonathan de Oliveira/Cuesta, Virginia. “Conciencia histórica y representaciones de identidad política de jóvenes en el Mercosur.” Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 13 (2014): 3-15.

Recursos da web

- Grupo de Estudos em Didática da História. http://gedhiblog.blogspot.com.br/ (Accesso em 13 dezembro 2016).

- Proyecto Zorzal. http://proyectozorzal.org/ (Accesso em 13 dezembro 2016).

_____________________

[1] Trecho de discurso da estudante Ana Júlia, participante das ocupações estudantis brasileiras, na Assembleia Legislativa do Estado do Paraná, em 26 de outubro de 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oY7DMbZ8B9Y (Acesso em 13 dezembro 2016).

[2] O projeto Jovens e História é desenvolvido sob a liderança de Luis Fernando Cerri, na Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa. Recentemente, um Seminário Nacional sintetizou discussões realizadas com os dados e parte das atividades está registrada no canal do YouTube do Grupo de Estudos em Didática da História:GEDHITUBE. https://www.youtube.com/user/GEDHITube (Acesso em 13 dezembro 2016).

[3] Foi utilizada a escala Likert. Valores próximos a zero significam média importância. Valores negativos significam pouca ou nenhuma importância. Os dados foram coletados em 2011 e 2012.

_____________________

Créditos da imagem

UNIFEMM Centro Universitário de Sete Lagoas © Public Domain via Flickr.

Citação recomendada

Pacievitch, Caroline: O que faz o mundo mudar? Jovens e história. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 4, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8254.

“Our difficulty in forming an opinion is much bigger than yours: We have to see everything that the media tells us, go through a process of understanding, of selecting, so we can see what we’re going to be in favor of – what we’re going to be against […].”[1] – Ana Júlia, Brazilian, sixteen-year-old high school student.

What Makes the World Change?

Street demonstrations and movements that have occupied schools and universities have moved the Brazilian political scene since at least July 2013. Traditionally, young people have been regarded as the embodiment of novelty and change. However, the short extract from young Ana Júlia’s speech demonstrates the relevance of the discourse which needs to be established at schools for teaching history. This is because all of us – both teachers and students – need time and dialogue to comprehend what happens around us and to find our place in the world.

Bearing this in mind, we have discovered a method to analyze the thoughts of young people from Mercosul countries on factors of change for the past and future. Data was collected by the research project Jovens & História (Young People & History), in which about 3,800 students aged fifteen from Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Chile participated.[2] Young people were asked to assess what influence some factors had in changing people’s lives from 1970 up until today and what impact they will have from now until 2050. The degree of influence each factor had was evaluated on a scale between very minor, minor, moderate, major and very major. The same options were available for the questions about the past and about the future.[3]

The intent of this questionnaire was to identify the most recurrent reasons given for changes in the past and future, and to find out if there were any differences of opinion between young people from different countries. Furthermore, the study aimed to confirm the fact that past narratives (causalities) and expectations for the future can be inferred. It also pondered on whether or not both the more frequently and less frequently selected reasons give an insight into young people’s perceptions about their roles as agents of history.

Students and Factors of Change

According to the students, the factors of change that have been more common from 1970 until today have been development of science and knowledge, technical inventions and mechanization, economic interests and economic competition, scientists and engineers and movements and social conflicts. The less recurrent factors have been founders of religions and religious leaders, philosophers, thinkers and well-educated people, personal effort and migration and employees’ organization. Moreover, the students deemed kings, presidents and politically important characters in power, political revolutions, environmental issues, wars and conflicts and political reforms to be of a moderate influence only.

Regarding factors of change for the future, students basically expect the relevance of each respective factor to remain, with the difference being that environmental issues become much more urgent. In addition to this, founders of religions and religious leaders and philosophers, thinkers and well-educated people were evaluated negatively on the whole. In the aftermath of the intense impact of the refugee “crisis” on Europe and escalating violence through religious-fundamentalist groups, it is tempting to wonder if students would still value the power of religion and migration as factors of change in the same way.

When comparing the responses of students from the four countries, we notice that Chile and Uruguay stand out from the others. Whilst Brazilian and Argentinian students remain closer to the overall average, the Argentinian students tend to be more pessimistic than others, especially regarding factors that center on individuals. Chilean students are positioned well above the overall average in movement factors and social conflicts, kings, presidents and politically important characters in power, political reforms, wars and conflicts, philosophers, thinkers, and well-educated people, political revolutions, and migration and workers’ organization. This may mean that Chilean students, and to some extent Uruguayan ones also, are more distant from a neutral position than the others. However, this is not reflected in their predictions for their future, where they remain closer to the average opinion.

Factors beyond control

In total, it seems evident that innovations in the field of technology and inventions along with economic interests and social conflicts were the most relevant factors for change, according to the evaluation of the students’ opinions. Individual and collective issues are among both the most relevant factors and the least relevant. However, the students undoubtedly prioritize factors over which they have little or no control. Scientists and engineers are the only ones who appear as relevant individuals, leading movements and social conflicts. Topics that are currently very prominent in the global political debate, such as religious leaders and migration, were not seen as influential at the time these young people answered the question.

The answers given by teachers participating in the same survey were very similar to those of young people. This could indicate a reflection of the participants’ historical culture. At the same time, could it also be evidence of a trend present in the history which is taught at school?

We infer, from these factors, that young people build a stable overview on the last and the next forty years in history. Apparently, traditional views on the history of heroes and great men and women are not relevant to the young participants. On the other hand, neither are the popular revolutions nor movements of workers the factors which apparently trigger change. It seems that the most important factors are those outside the control of everyday life: technology, innovation, engineering and major economic issues have been determining what has changed and what will change in the timespan of a generation.

Addressing Decision-making Processes!

Thus, we could celebrate the absence of factors such as “great men and women” and “battles” among students’ favorites, as this shows a victory over traditional historical narratives. Alternatively, however, we could lament the fact that both workers’ movements and personal effort (according to the inclination of each) receive little attention. Either way, it is pertinent to question how young people see themselves as agents during the course of their lives and how they make decisions.

Doubtlessly, the intense mobilization of recent months suggests there is scope for hope in times ahead. Perhaps the collective historical culture represents a source of problematization for understanding the historical agency of young people, particularly with regard to historical change. Hence the anguish of Ana Júlia when faced with the whirlwind of information that seemingly lies beyond her control. Should history taught at school, therefore, be more concerned about factors of change for the past and for the future and mobilize such understandings in the classroom?

This brief overview reinforces the constant challenge regarding teachers’ education as well as the production of learning materials: problematizing and understanding change in time by focusing mainly on decision-making and mobilization to build new history – a task that, as we know, does not only belong to young people.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Pacievitch, Caroline, and Luis Fernando Cerri. “Professores de História e sua relação com a política: uma abordagem comparativa na América do Sul.” Opsis 15 (2015): 516-536.

- Cerri, Luis Fernando, Jonathan de Oliveira Morlar, and Virginia Cuesta. “Conciencia histórica y representaciones de identidad política de jóvenes en el Mercosur.” Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 13 (2014): 3-15.

Web Resources

- Grupo de Estudos em Didática da História. http://gedhiblog.blogspot.com.br/ (last accessed 13 December).

- Proyecto Zorzal. http://proyectozorzal.org/ (last accessed 13 December 13 2016).

_____________________

[1] Excerpt from the speech of student Ana Júlia—participant of Brazilian students’ occupations of schools. Speech held in the Legislative Assembly of the State of Paraná, Brazil, October 26, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oY7DMbZ8B9Y (last accessed 13 December 2016).

[2] The Jovens & História project is developed under the leadership of Luis Fernando Cerri at State University of Ponta Grossa. Recently, a National Seminar assembled discussions with data, and some of the activities are registered on the YouTube channel of Grupo de Estudos em Didática Da História (Study Group on History Didactics): GEDHITUBE. https://www.youtube.com/user/GEDHITube (last accessed 13 December 2016).

[3] The Likert-scale was used. Values close to zero denote average importance. Negative values denote little or no importance. Data was collected in 2011 and 2012.

_____________________

Image Credits

UNIFEMM Centro Universitário de Sete Lagoas © Public Domain via Flickr.

Recommended Citation

Pacievitch, Caroline: What Makes the World Change? Young People and History. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 4, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8254.

“Unsere Schwierigkeit, uns eine Meinung zu bilden, ist viel größer als eure: Wir müssen alles, was uns die Medien mitteilen, aufnehmen, müssen das Gehörte verarbeiten, bewerten, damit wir begreifen können, wofür wir stehen – und was wir vermeiden wollen […].”[1] – Ana Júlia, Brasilianerin, sechzehnjährige Schülerin.

Was verändert die Welt?

Spätestens seit Juli 2013 beschäftigen die brasilianische Politik Straßendemonstrationen und soziale Bewegungen, die Schulen und Universitäten besetzt haben. Ursprünglich galt die Jugend als Verkörperung des Neuen und des Wandels. Der kurze Auszug aus Ana Júlias Rede belegt jedoch die Wichtigkeit des Diskurses, der im Geschichtsunterricht an den Schulen etabliert werden muss, weil wir alle – LehrerInnen wie SchülerInnen – Zeit und Dialoge benötigen, um das Geschehen um uns herum zu begreifen und um unseren Platz in der Welt zu finden.

Wenn wir dies berücksichtigen, haben wir eine Möglichkeit, die Meinung Jugendlicher aus Mercosul-Ländern über die Ursachen des Wandels in der Vergangenheit und in der Zukunft zu analysieren. Das Forschungsprojekt Jovens & História (Jugend & Geschichte) sammelte Daten von rund 3.800 fünfzehnjährigen SchülerInnen aus Brasilien, Argentinien, Uruguay und Chile.[2] Die Jugendlichen wurden aufgefordert, die Faktoren für Veränderung, die das Leben der Menschen von 1970 bis zum heutigen Tag beeinflusst haben und die das Leben von heute bis 2050 beeinflussen werden, zu bewerten. Der Einfluss der jeweiligen Faktoren wurde mittels einer Skala von sehr gering, gering, mittelmäßig, gravierend und sehr gravierend ermittelt. Die gleichen Auswahlmöglichkeiten bezogen sich auch auf Fragen über die Vergangenheit und die Zukunft.[3]

Der Fragebogen zielte darauf ab, die am häufigsten angegebenen Erklärungen für Veränderungen in der Vergangenheit und Zukunft zu prüfen und herauszufinden, ob zwischen den Jugendlichen aus den ausgewählten Ländern unterschiedliche Meinungen bestehen. Außerdem versuchte die Studie, aus Geschichtserzählungen (Kausalitäten) und den Erwartungen für die Zukunft Schlüsse zu ziehen. Zudem sollte herausgefunden werden, inwieweit die Faktoren, die am häufigsten und am seltensten ausgewählt wurden, einen Einblick in die Wahrnehmungen junger Leute bezüglich ihrer Rolle als historische Akteure geben.

SchülerInnen und Faktoren für Veränderungen

Den SchülerInnen zufolge sind die am weitverbreitetsten Faktoren, die einen Wandel seit 1970 bis zum heutigen Tag auslösten, folgende: wissenschaftliche Fortschritte, technische Errungenschaften und Mechanisierung, wirtschaftliche Interessen und Wettbewerb, WissenschaftlerInnen und IngenieurInnen sowie soziale Bewegungen und soziale Konflikte. Unter die weniger verbreiteten Faktoren fallen ReligionsgründerInnen und -oberhäupter, PhilosophInnen, DenkerInnen und AkademikerInnen, persönliches Engagement und Migration und Arbeitnehmerverbände. KönigInnen, PräsidentInnen und weitere politisch mächtige Personen, politische Revolutionen, Umweltfragen, Kriege und Konflikte sowie politische Reformen haben für die SchülerInnen lediglich moderaten Einfluss.

Was die zukünftigen Veränderungen anbelangt, gehen die SchülerInnen vorwiegend von der gleichen Relevanz der Faktoren aus. Als einzige Ausnahme wird Umweltfragen mehr Dringlichkeit zugeordnet. Darüber hinaus werden ReligionsgründerInnen und -oberhäupter, PhilosophInnen, DenkerInnen und AkademikerInnen im Allgemeinen negativ bewertet. Im Zusammenhang mit der europäischen Flüchtlingskrise und dem religiösen Fundamentalismus, der zunehmend an Bedeutung gewinnt, stellt sich die Frage, ob die SchülerInnen die Macht der Religion und die Migration als Faktoren der Veränderung weiterhin auf die gleiche Art und Weise beurteilen.

Vergleicht man die Antworten der SchülerInnen aus den vier Ländern, wird der Unterschied zu Chile und Uruguay deutlich. Während die brasilianischen und argentinischen SchülerInnen in ihren Aussagen mehr oder weniger dem Gesamtdurchschnitt entsprechen, zeigen sich argentinische SchülerInnen, besonders in Hinblick auf Faktoren, die sich auf Einzelpersonen beziehen, pessimistischer als die anderen. Chilenische SchülerInnen bewerten soziale Bewegungen und soziale Konflikte, KönigInnen, PräsidentInnen und weitere politisch mächtige Personen, politische Reformen, Kriege und Konflikte, PhilosophInnen, DenkerInnen und AkademikerInnen, politische Revolutionen und Migration sowie Gewerkschaften über dem Durchschnitt. Das könnte bedeuten, dass chilenische und bis zu einem gewissen Grad auch uruguayische SchülerInnen eine weniger neutrale Position einnehmen als andere. In deren Zukunftsprognosen ist dies jedoch nicht spürbar; diese überschneiden sich weitgehend mit der allgemeinen Meinung.

Faktoren jenseits von Kontrolle

Die Evaluierung der Meinungen der SchülerInnen zeigt insgesamt, dass technologische Innovationen und Erfindungen sowie ökonomische Interessen und soziale Konflikte als wichtigste Faktoren für einen Wandel betrachtet werden. Individuelle und kollektive Faktoren finden sich sowohl bei den wichtigsten als auch bei den unwichtigsten Faktoren. Ohne Zweifel favorisieren die SchülerInnen jedoch Faktoren, die sie nur wenig bis gar nicht beeinflussen können. WissenschaftlerInnen und IngenieurInnen sind die einzigen, die als relevante Individuen vorkommen und welche die Rubriken soziale Bewegungen und soziale Konflikte übertreffen. Prominente Themen, wie unter anderem Religionsoberhäupter und Migration, die momentan die globale politische Debatte bewegen, schienen zur Zeit der Befragung der Jugendlichen nicht von Interesse zu sein.

Die Antworten der teilnehmenden LehrerInnen in der gleichen Umfrage waren jenen der Jugendlichen sehr ähnlich, wobei dies auf ein kollektives historisches Gedächtnis der TeilnehmerInnen zurückgeführt werden könnte. Weist das aber auch auf den aktuellen Zustand des Geschichtsunterrichts hin?

Aus den Ergebnissen der Umfrage können wir schließen, dass sich die Jugendlichen einen stabilen Überblick über die letzten und nächsten vierzig Jahre gebildet haben. Geglaubte traditionelle Weltanschauungen über die Geschichte von Helden und großen Persönlichkeiten sind für die jungen TeilnehmerInnen nicht relevant. Ebenso zählen für sie weder populäre Revolutionen noch Arbeiterbewegungen zu den Faktoren, die einen Wandel hervorrufen. Es scheint, die einflussreichsten Faktoren sind jene außerhalb ihrer Kontrolle: Technologie, Innovation, Ingenieurwesen und wichtige wirtschaftliche Faktoren bestimmten den Wandel der letzten Generation und werden ihn weiterhin noch bestimmen.

Entscheidungsprozesse thematisieren!

Einerseits freut es zu hören, dass die SchülerInnen Faktoren wie “wichtige Persönlichkeiten” und “Schlachten” nicht favorisieren, was einem Triumph über traditionelle Geschichtserzählungen gleichkommt. Andererseits ist jedoch zu bedauern, dass sowohl Arbeiterbewegungen als auch persönliches Engagement (je nach Neigung) wenig anerkannt werden. So oder so ist es relevant nachzufragen, wie sich Jugendliche in ihrem Leben als historische Akteure sehen und wie sie Entscheidungen treffen.

Zweifellos bedeutet die intensive Mobilisierung der letzten Monate Hoffnung für die Zukunft. Vielleicht steht das kollektive historische Gedächtnis sogar dafür, dass Jugendliche ihre Rolle als Akteure der Geschichte problematisieren, vor allem in Bezug auf den technischen Wandel. So lässt sich Ana Júlias Verzweiflung erklären, wenn sie mit der nichtkontrollierbaren Informationsflut konfrontiert wird. Sollte sich daher der Geschichtsunterricht mehr mit den Ursachen des Wandels in der Vergangenheit und Zukunft befassen und solche Verständnisfragen im Klassenzimmer behandeln?

Dieser kurze Überblick bekräftigt die steten Herausforderungen in der LehrerInnenausbildung sowie in der Zusammenstellung des Lehrmaterials: Veränderungen zu problematisieren und zu verstehen, indem ein Fokus auf Entscheidungsprozesse gelegt und angeregt wird, Geschichte neu zu konstruieren – eine Aufgabe, die, wie wir alle wissen, nicht nur auf die Jugend zu beschränken ist.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Caroline Pacievitch/Luis Fernando Cerri: Professores de História e sua relação com a política: uma abordagem comparativa na América do Sul. In: Opsis 15 (2015), S. 516-536.

- Luis Fernando Cerri/Jonathan de Oliveira Morlar/Virginia Cuesta: Conciencia histórica y representaciones de identidad política de jóvenes en el Mercosur. In: Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 13 (2014), S. 3-15.

Webressourcen

- Grupo de Estudos em Didática da História: http://gedhiblog.blogspot.com.br/ (letzter Zugriff 13.12.2016).

- Proyecto Zorzal: http://proyectozorzal.org/ (letzter Zugriff 13.12.2016).

_____________________

[1] Exzerpt der Rede der Schülerin Ana Júlia – Teilnehmerin der brasilianischen Studentenbesetzungen von Schulen. Rede abgehalten in der gesetzgebenden Versammlung des Bundesstaats Paraná, Brasilien, 26.10.2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oY7DMbZ8B9Y> (letzter Zugriff 13.12.2016).

[2] Das Projekt Jovens & História wird unter der Leitung von Luis Fernando Cerri an der State University of Ponta Grossa geführt. Vor kurzem hat das National Seminar Diskussionen mit Daten zusammengestellt und Teile der Arbeit auf YouTube unter Grupo de Estudos em Didática Da História (StudentInnengruppe über Geschichtsdidaktik) online gestellt: GEDHITUBE. https://www.youtube.com/user/GEDHITube> (letzter Zugriff 13.12.2016).

[3] Es wurde eine Likert-Skala verwendet. Werte im Nullbereich stehen für durchschnittliche Wichtigkeit. Negative Werte stehen für wenig bis keine Wichtigkeit. Die Daten wurden 2011 und 2012 zusammengetragen.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

UNIFEMM Centro Universitário de Sete Lagoas © Public Domain via Flickr.

Übersetzung

Stefanie Svacina und Paul Jones (paul.stefanie at outlook.at)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Pacievitch, Caroline: Was verändert die Welt? Jugend und Geschichte. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 4, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8254.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 4

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8254

Tags: Argentina (Argentinien), Brazil (Brasilien), Chile, Empiricism (Empirie), Language: Portuguese, Narratives (Narrative), Uruguay

Leave a Reply