Abstract: Is patriotism alive? Does it influence citizens’ historical representations? As for many other issues, George Orwell, during WW II, was lucidly able to anticipate its importance when he said: “One cannot see the modern world as it is, unless one recognizes the overwhelming strength of patriotism, national loyalty. In certain circumstances, it may crumble; at certain levels of civilization, it does not exist; yet as a positive force, there is nothing comparable. Next to it, Christianity and international socialism are weak as hay.” [1]

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5216.

Languages: English, Deutsch

Is patriotism alive? Does it influence citizens’ historical representations? As for many other issues, George Orwell, during WW II, was lucidly able to anticipate its importance when he said: “One cannot see the modern world as it is, unless one recognizes the overwhelming strength of patriotism, national loyalty. In certain circumstances, it may crumble; at certain levels of civilization, it does not exist; yet as a positive force, there is nothing comparable. Next to it, Christianity and international socialism are weak as hay.”[1]

A Revival?

One can argue that, after WW II, patriotism and its presence in public history remained, generally, a rather old fashioned question until 9/11 (2001), when it came to life again. “For the love of a country” (2002) by the North American philosopher Martha Nussbaum is a good example of this revival of heated debates on patriotism. More recently, many political scientists have established a clear relationship between the terrorist attacks in France in November 2015 and the political victories of the French “Front National”, whose extreme right wing patriotic views are an essential part of its political message. Therefore, it should be admitted that patriotism is very much alive and that it certainly influences citizens’ social and political views in general and their historical representations in particular.

Mechanisms

But how do patriotic views transmit and influence historical representations? Some of my research has tried to show that they make use of three cognitive operations that definitely have an impact on the way historical master narratives are consumed by citizens. These three operations are:

– Firstly, identification of past and present, understood as a lack of

differentiation that considers national identity as a natural and transcendental category.

– Secondly, idealization of the past that considers it as a moral, heroic or patriotic example.

– Finally, teleological predetermination of the past that considers the result of a historical process in the present as its inherent goal.

I am referring to a recent study that comprises a comparative analysis of Argentinian high school students’ master narratives about the independence process of their country by 1810. It also contains a comparative analysis of speeches given by former Argentinian President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and current US President Barack Obama. In both cases, the similarities with students’ historical views become very clear.[2]

Different but Similar

In sum, patriotism is still influencing the historical views of students in a rather similar way, at least when both South and North American nations are compared. The underlying mechanism of patriotism and master narrative is the same. Thus, patriotic rituals occupy a central place in all North and South American educational systems. Although patriotic rituals are separate from the curricular contents of history, students and teachers in these continents establish many relationships between these two domains. As a matter of fact, this is not very surprising, because most of the master narratives of Latin American (i.e. South American) countries about their independence are basically based on the corresponding master narrative from the United States of America. Another coincidence is related to how influential the so-called “living history sites” are in these countries, especially the ones related to the battles of the respective independence war. They are visited by millions of citizens every year. No doubt these sites transmit a patriotic view of history. These rituals are also very closely related to the Pledge of Allegiance and to the important symbolic role played by national flags in the schools of South and North America.

Varieties of Patriotism

However, patriotism is not only an educational issue but also a political one. In this respect, it is interesting to see how the Washington Post, on 3 June 2015, presented an interesting analysis of Obama’s patriotic views. It develops the idea of a clear difference between two different types of patriotic interpretations of the United States of America.[3] One, formulated by President Reagan and some other Republican leaders, is based on a historical essentialism in which historical figures play a role as if they were living in the present. On the other hand, the historical patriotic interpretation of President Obama is based on a constructive relationship between past, present and future, in which past symbols are used as an inspiration for new, unresolved and challenging problems.

For example, Obama said, “But what greater expression of faith in the American idea; what greater form of patriotism is there than to believe that America is not yet finished; that it’s strong enough to be self critical; that each generation can look upon its imperfections and say we can do better.”[3]

As a matter of fact, the main speech analysed in the study[2] is precisely the one delivered on 28 March 2015 at the bridge near Selma (Alabama) where 50 years of political resistance against racism and discrimination were commemorated. Nevertheless, essentialism is still playing a significant role in Obama’s historical views. For example, he refers to American exceptionalism as being a part of the nation’s “DNA”. I think that this comparison of biological and cultural dimensions of human beings is not meant to provide insights into the way the patriotic notion of exceptionalism was constructed. On the contrary, it is a very clear example of historical essentialism. Instead of considering the so-called American exceptionalism and “moral superiority” as a result of a number of social, political and economic factors, it is depicted as a pre-existing “biological” cause.

In sum, there are several varieties of patriotic political and educational expressions in various countries but they share some common mechanisms, like those described above.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Nussbaum, Martha (Ed.): For love of country?: A new democracy forum on the limits of patriotism, Boston, MA 2002.

- Van Alphen, Floor / Carretero, Mario: The Construction of the Relation Between National Past and present in the Appropriation of Historical Master Narratives. In: Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 49 (2015), pp. 512-530.

Web Resources

- Commemoration of the 203rd anniversary of the May Revolution: Words from the President of the Nation (25-05-2013) – http://www.casarosada.gov.ar/discursos/26500-conmemoracion-del-203daniversario-de-la-revolucion-de-mayo-palabras-de-la-presidenta-de-la-nacion (last accessed 22.01.2016)

- Obama speeches can be found at – http://obamaspeeches.com (last accessed 22.01.2016)

- The practice of patriotic activities can be seen at – http://livinghistorysites.com (last accessed 22.01.2016)

____________________

[1] Orwell, G. (2002). The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius – Part 1: England Your England. First published: London 1941, http://wikilivres.ca/wiki/The_Lion_and_the_Unicorn/Part_1 (last accessed 30.12.2015).

[2] Van Alphen, F. & Carretero, M. (2015) The Construction of the Relation Between National Past and present in the Appropriation of Historical Master Narratives. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 49, 3, 512-530.

[3] Jaffe, G. (2015) Obama´s new patriotism. The Washington Post. June, 3, http://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/national/2015/06/03/obama-and-american-exceptionalism/ (last accessed 22.1.2016).

_____________________

Image Credits

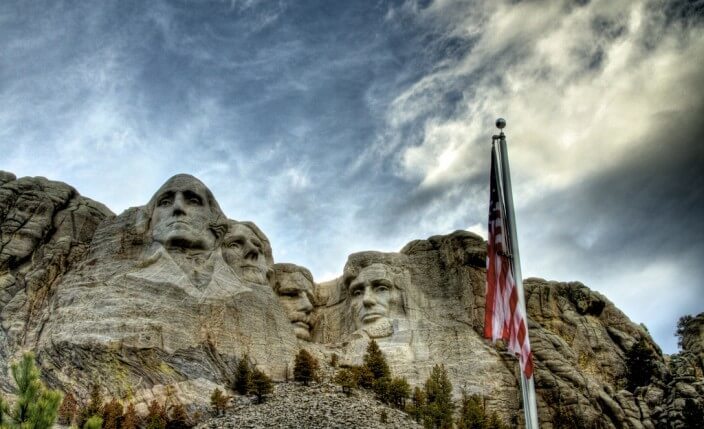

Founding Father @ Zach Discerner, 2010 (CC BY 2.0) – https://www.flickr.com/photos/zachd1_618/4680704222/in/photolist-88BQhW (Last accessed 2.1.2016)

Recommended Citation

Carretero, Mario: Varieties of Patriotism And Public History. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5216.

Lebt der Patriotismus? Beeinflusst er die historischen Vorstellungen der BürgerInnen? Wie in so vielen anderen Fällen, hat George Orwell während des 2. Weltkriegs die Relevanz des Patriotismus antizipiert: “Man kann das Wesen der modernen Welt nicht sehen, wenn man die überwältigende Kraft des Patriotismus, der nationalen Loyalität, nicht erkennt. Unter bestimmten Bedingungen kann er bröckeln; auf bestimmten Ebenen der Zivilisation existiert er nicht; aber, als eine positive Kraft ist er mit nichts vergleichbar. Neben ihm sind Christentum und der internationale Sozialismus so schwach wie Heu.”[1]

Eine Reanimation?

Man kann die Meinung vertreten, dass nach dem 2. Weltkrieg der Patriotismus und seine Bedeutung für die Public History im Allgemeinen eine etwas altmodische Sache geblieben sei – bis er durch “9/11” 2001 wieder lebendig wurde. Das von der nordamerikanischen Philosophin Martha Nussbaum herausgegebene Buch “For the love of a country” (2002) ist ein gutes Beispiel für diese Wiederbelebung der hitzigen Debatten über Patriotismus. Vor Kurzem haben zahlreiche PolitikwissenschaftlerInnen eine klare Beziehung zwischen den terroristischen Angriffen in Frankreich in 2015 und den politischen Siegen des französischen “Front National” nachgewiesen, dessen extrem rechtsradikal-patriotische Ansichten ein ganz wesentlicher Teil seiner politischen Botschaft sind. Es muss daher wohl zugestanden werden, dass Patriotismus durchaus lebendig ist und dass er definitiv die sozialen und politischen Ansichten der BürgerInnen im Allgemeinen und deren historische Vorstellungen im Besonderen beeinflusst.

Mechanismen

Aber wie übermitteln patriotische Ansichten historische Vorstellungen und wie beeinflussen sie diese? Ein Teil meiner Forschung versuchte zu zeigen, dass dabei drei kognitive Vorgänge zur Anwendung gelangen, die mit Sicherheit auf die Art, wie historische Master-Narrative durch BürgerInnen aufgenommen werden, eine Wirkung ausüben. Diese drei Vorgänge sind:

– Erstens: Identifikation von Vergangenheit und Gegenwart verstanden als das Fehlen einer Differenzierung, womit nationale Identität als eine natürliche und transzendente Kategorie betrachtet wird.

– Zweitens: Idealisierung der Vergangenheit, die diese als ein moralisches, heroisches oder patriotisches Beispiel betrachtet.

– Drittens: teleologische Vorbestimmung der Vergangenheit, welche die Ergebnisse eines historischen Prozesses in der Gegenwart als ihr inhärentes Ziel betrachtet.

Ich beziehe mich auf eine neuere Studie, die sich mit einer vergleichenden Analyse beschäftigt, in der die Master-Narrative argentinischer Highschool-SchülerInnen zum Unabhängigkeitsprozess ihres Landes im Jahr 1810 untersucht wurden. Diese Studie beinhaltet auch einen Vergleich zwischen Reden der ehemaligen argentinischen Präsidentin Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner und des amtierenden US-amerikanischen Präsidenten Barack Obama. In beiden Fällen wurden die Ähnlichkeiten mit den historischen Ansichten der SchülerInnen sehr deutlich.[2]

Anders, aber ähnlich

Insgesamt sind die historischen Ansichten von SchülerInnen in recht ähnlicher Weise noch immer von Patriotismus beeinflusst, zumindest wenn Nationen in Nord- und Südamerika verglichen werden. Der zugrundeliegende Mechanismus von Patriotismus und Master-Narrativ ist derselbe. Dementsprechend nehmen patriotische Rituale eine zentrale Stelle in allen nord- und südamerikanischen Bildungssystemen ein. Obwohl patriotische Rituale unabhängig von den Lehrplanvorgaben für Geschichte sind, stellen sowohl Lernende wie auch Lehrende auf beiden Kontinenten viele Beziehungen zwischen den beiden Bereichen her. Dies ist in der Tat nicht besonders überraschend, da die meisten lateinamerikanischen (d.h. südamerikanischen) Master-Narrative über die Unabhängigkeit ihrer Länder im Wesentlichen auf dem entsprechenden Narrativ aus den USA basieren. Eine weitere Übereinstimmung bezieht sich darauf, wie einflussreich sogenannte “living history sites” in diesen Ländern sind, besonders die zu jenen Orten, wo die jeweiligen Unabhängigkeitskämpfe statt fanden. Diese werden jährlich von Millionen von BürgerInnen besucht. Zweifellos vermitteln solche Orte eine patriotische Ansicht von Geschichte. Diese Rituale sind auch sehr eng mit dem Treueschwur und mit der wichtigen symbolischen Rolle verbunden, die Nationalflaggen in den Schulen Nord- und Südamerikas spielen.

Spielarten des Patriotismus

Allerdings ist Patriotismus nicht nur eine Frage des Unterrichts, sondern auch eine der Politik. In diesem Zusammenhang ist eine bemerkenswerte Analyse der patriotischen Ansichten Obamas in der Washington Post vom 3. Juni 2015 von besonderem Interesse. Darin wird die Idee eines klaren Unterschieds zwischen zwei Arten patriotischer Deutung der USA entwickelt.[3] Eine, die von Präsident Reagan und einigen anderen republikanischen Führern formuliert wurde, basiert auf einem historischen Essentialismus, bei der historische Figuren eine Rolle spielen, als ob sie in der Gegenwart leben würden. Im Gegensatz dazu basiert die historisch patriotische Deutung von Präsident Obama auf einer konstruktiven Beziehung zwischen Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft. In dieser Interpretation werden Symbole aus der Vergangenheit als Inspiration für neue, ungelöste und herausfordernde Probleme verwendet.

Obama sagte zum Beispiel: “Aber welch größeren Ausdruck von Vertrauen in die amerikanischen Idee, welch größere Art von Patriotismus gibt es, als zu glauben, dass Amerika noch nicht vollkommen ist; dass es stark genug ist, selbstkritisch zu sein: dass jede Generation ihre Unvollkommenheiten ins Auge fassen und sagen kann: ‘Wir können uns verbessern.'”[3]

Tatsächlich ist die in der Studie[2] analysierte Rede genau diejenige, die am 28. März 2015 an der Brücke in der Nähe von Selma (Alabama) gehalten wurde, als an 50 Jahre politischen Widerstand gegen Rassismus und Diskriminierung erinnert wurde. Trotzdem spielt Essentialismus eine wichtige Rolle in Obamas historischen Ansichten. Er verweist zum Beispiel darauf, dass der amerikanische Exzeptionalismus Teil der nationalen “DNA” sei. Meiner Meinung nach soll diese Analogie zwischen den biologischen und kulturellen Dimensionen des Menschseins keine Einsichten dafür liefern, wie die patriotische Vorstellung des Exzeptionalismus entstanden ist. Es ist im Gegenteil sogar ein eindeutiges Beispiel von Essentialismus. Statt den sogenannten amerikanischen Exzeptionalismus und die “moralische Überlegenheit” als das Ergebnis einer Reihe von sozialen, politischen und ökonomischen Faktoren zu betrachten, wird er als eine bereits vorhandene, “biologische” Ursache dargestellt.

Alles in allem gibt es in den verschiedenen Ländern unterschiedliche Arten von politischen und pädagogischen Ausprägungen des Patriotismus – aber sie haben manche geläufige Mechanismen gemeinsam, wie die oben beschriebenen.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Nussbaum, Martha (Hg.): For love of country? A new democracy forum on the limits of patriotism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press 2002.

- Van Alphen, Floor & Carretero, Mario: The Construction of the Relation Between National Past and present in the Appropriation of Historical Master Narratives. In: Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 49 (2015), S. 512-530.

Webressourcen

- Gedenken des 203. Jahrestages der Mai-Revolution: Ansprache der Präsidentin (25. Mai 2013) – http://www.casarosada.gov.ar/discursos/26500-conmemoracion-del-203daniversario-de-la-revolucion-de-mayo-palabras-de-la-presidenta-de-la-nacion (letzter Abruf 22.01.2016)

- Die Reden Obamas sind zu finden bei – http://obamaspeeches.com (letzter Abruf 22.01.2016)

- Die Praxis patriotischer Aktivitäten kann eingesehen werden bei – http://livinghistorysites.com (letzter Abruf 22.01.2016)

____________________

[1] Orwell, G.: The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius – Part 1: England Your England, 2002. Erstpublikation: London 1941, http://wikilivres.ca/wiki/The_Lion_and_the_Unicorn/Part_1 (letzter Abruf 30.12.2015).

[2] Van Alphen, F. & Carretero, M.: The Construction of the Relation Between National Past and present in the Appropriation of Historical Master Narratives. In: Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 49 (2015), H. 3, S. 512-530.

[3] Jaffe, G.: Obama´s new patriotism. In: The Washington Post, 3. Juni 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/national/2015/06/03/obama-and-american-exceptionalism/ (letzter Abruf 30.12.2015).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Founding Father @ Zach Discerner, 2010 (CC BY 2.0) – https://www.flickr.com/photos/zachd1_618/4680704222/in/photolist-88BQhW (Letzter Abruf 2.1.2016)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Carretero, Mario: Spielarten des Patriotismus und der Public History. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5216.

Copyright (c) 2016 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 4 (2016) 3

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5216

Tags: Argentina (Argentinien), Concepts of History (Geschichtsbild), Patriotism (Patriotismus), USA