Abstract:

In recent years, citizen participation has increased considerably. The sector of cultural heritage has been confronted with the phenomenon of rapid transformation based on participant involvement. One of the main effects has been the explosion of digital collaborative platforms. The article proposes the term ‘cultural collaborative platform’ to refer to any digital environment that allows audiences to contribute to the construction of knowledge related to cultural objects in interaction with one or more cultural institutions.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-19327.

Languages: Italian, English

La partecipazione dei cittadini al mondo dei beni culturali è particolarmente favorita nell’ecosistema digitale dalle piattaforme collaborative. Ma ci sono differenze sostanziali tra ambienti amatoriali e ambienti istituzionali. Nessuno dei due è neutro: nei primi la partecipazione è condizionata da visioni politico/ideologiche, nei secondi da protocolli di scientificità.

Ecosistemi digitali per la collaborazione

Negli ultimi anni, la partecipazione dei cittadini è aumentata considerevolmente in campi diversi come la politica, l’economia, i media e la cultura. Dalla democrazia partecipativa all’economia collaborativa, dal crowdsourcing alle tecnologie civiche, queste nuove forme di organizzazione politica, economica e tecnologica stanno cambiando la nostra società. Le tecnologie digitali hanno dato impulso a questa tendenza offrendo nuove possibilità di espressione e funzionando come leva per l’innovazione. Inoltre, la diffusione della cultura digitale, al di là degli strumenti stessi, ha favorito un cambiamento fondato sull’empowerment dei cittadini e l’espressione creativa della libertà individuale.

In questo contesto di “partecipazione onnipresente”, anche il settore dei beni culturali si è confrontato alla problematica di integrare i cittadini nelle sue attività. Uno dei principali effetti è stata l’esplosione delle piattaforme collaborative digitali, cioè di dispositivi digitali che permettono ai partecipanti, chiamati anche dilettanti, di esprimersi pubblicando o commentando contenuti sugli oggetti culturali che loro sono cari. Il web, prima con i blog e gli altri strumenti del web 2.0 e poi con i social network e le piattaforme di crowdsourcing, ha permesso ai “dilettanti-professionisti” (pro-am) di condividere e diffondere le loro conoscenze al grande pubblico in nuovi spazi digitali basati essenzialmente sulla democratizzazione delle possibilità espressive. In sintonia con questa nuova tendenza, diverse istituzioni hanno iniziato a utilizzare questo tipo di strumenti per permettere ai cittadini di partecipare alle loro attività. Oggi, le piattaforme collaborative (istituzionali, commerciali o associative) sono viste come vettori di nuove forme di impegno, di condivisione e di diffusione della conoscenza nel campo del patrimonio culturale.

La ricerca su questa tematica tende a identificare e descrivere due fenomeni opposti: da una parte le piattaforme amatoriali e dall’altra le piattaforme istituzionali. Questo articolo presenterà brevemente queste due direzioni di ricerca e nell’ultima parte argomenterà l’interesse di superare questa opposizione per comprendere pienamente l’impatto di questo fenomeno nel settore dei beni culturali.

Piattaforme amatoriali

Le piattaforme amatoriali sono iniziative digitali portate avanti spontaneamente da gruppi di dilettanti, artisti o fan, che possono basarsi su dispositivi commerciali (per esempio Soundcloud o YouTube) o associativi (per esempio Wikipedia). Questi dispositivi offrono due principali opportunità ai partecipanti: la possibilità di costruire la loro identità digitale e rinforzare la loro e-reputation, e l’opportunità di esprimersi attraverso la scrittura e la redazione.

La piattaforma digitale che ha attirato più appassionati è senza dubbio Wikipedia. Wikipedia è al primo posto, sia per la massa di contenuti creati in modo partecipativo, sia per il numero di collaboratori che hanno contribuito a questa avventura. Lanciata nel 2001, questa piattaforma riunisce oggi (ottobre 2021) più di 40 milioni di articoli e più di 16.000 redattori attivi solo per la versione inglese. Rispetto ad altre iniziative, la sua peculiarità è il suo approccio generalista che la rende la prima enciclopedia online. I suoi contenuti devono essere imparziali, non originali e supportati da fonti valide, come i contenuti di un’enciclopedia.

Oltre a Wikipedia, migliaia di altre piattaforme sono state create (e spesso sono già scomparse) per soddisfare le esigenze di appassionati, artisti o fan, in diversi campi culturali. Per la musica, possiamo citare i siti di creazione e autopromozione come MySpace o SoundCloud (così come quelli di consumo, in particolare le piattaforme di ascolto in streaming come Spotify). Quando si tratta di fotografia, l’artista e il fan spesso si sovrappongono. Su Flickr, le folksonomie sono emerse come strumenti di socialità e strutturazione sociale. Se consideriamo il mondo della letteratura, dobbiamo distinguere le piattaforme pensate per gli autori come Wattpad da quelle dedicate alla critica letteraria come Goodreads e Anobii. L’attenzione dei ricercatori che si interessano a queste piattaforme amatoriali si sta spostando sempre di più, abbandonando lo studio delle pratiche dei partecipanti per concentrarsi sulle politiche delle piattaforme. Lungi dall’essere degli spazi neutri di espressione, queste piattaforme non solo determinano gli stili di scrittura dei partecipanti, ma anche giocano un ruolo di prescrizione culturale attraverso i loro algoritmi di classificazione.

Piattaforme istituzionali

Nel contesto istituzionale, il termine “piattaforma collaborativa” identifica generalmente un dispositivo digitale (messo a disposizione da un’istituzione) dove il volontario non professionista può partecipare alla costruzione della conoscenza relativa ai beni culturali gestiti dall’istituzione. La diffusione di queste piattaforme è strettamente legata al recente successo della citizen science, un movimento scientifico che mira a integrare i cittadini nei processi di costruzione della conoscenza scientifica. Queste piattaforme istituzionali si sono sviluppate accanto a quelle amatoriali come fenomeno del tutto autonomo. Infatti, le istituzioni culturali preferiscono costruire piattaforme ad hoc piuttosto che affidarsi a sistemi preesistenti come i social network. Le piattaforme amatoriali non sembrano adatte agli obiettivi scientifici delle istituzioni e non sembrano garantire gli standard di qualità necessari. Diventa allora necessario costruire dispositivi istituzionali che possano permettere di coinvolgere il dilettante secondo le esigenze istituzionali.

Numerose istituzioni hanno lanciato applicazioni di citizen science. È il caso dei progetti ospitati sulla piattaforma Zooniverse, in particolare il progetto AnnoTate che permette di trascrivere documenti di artisti conservati negli archivi della Tate, o il progetto Shakespeare’s World che offre la possibilità di trascrivere documenti scritti a mano dai contemporanei di Shakespeare (1564-1616). Inoltre, le principali biblioteche internazionali hanno lanciato il loro portale di trascrizione, per esempio la British Library ha molti progetti su LibCrowd. In modo simile, Europeana, che riunisce le risorse delle istituzioni culturali di tutta Europa, ha aperto la sua sezione partecipativa sul sito Europeana Transcribe dedicata ai documenti della Prima guerra mondiale.

Lo strumento collaborativo istituzionale più diffuso è il crowdsourcing, cioè un dispositivo che permette al pubblico di svolgere compiti semplici, come la trascrizione di testi scritti a mano o l’indicizzazione di documenti, per aiutare l’istituzione a costruire banche dati sul patrimonio culturale, utili alla sua salvaguardia. L’obiettivo principale delle piattaforme di crowdsourcing è quello di produrre dati standardizzati che possano essere integrati nei database dell’istituzione. Molti archivi comunali e dipartimentali hanno lanciato progetti di indicizzazione collaborativa. Per esempio, l’Archivio Nazionale Francese ha lanciato nel 2018 il progetto Testaments de Poilus, una piattaforma dove i dilettanti possono trascrivere i testamenti dei soldati della Grande Guerra. Attraverso questo dispositivo, non solo i volontari trascrivono, ma codificano anche i documenti in formato TEI (Markup Format for Textual Records). Anche se il compito è molto impegnativo, l’istituzione non ha nemmeno il tempo di pubblicare nuovi documenti che sono già trascritti. Inoltre, le trascrizioni sono generalmente convalidate da altri volontari, senza bisogno dell’intervento dei professionisti. Tutte queste piattaforme istituzionali hanno in comune il fatto che definiscono un protocollo top-down che standardizza la partecipazione del dilettante per garantire la qualità scientifica dei contributi.

L’incontro tra amatoriale e istituzionale

Le piattaforme amatoriali e istituzionali sono state raramente messe in relazione. I ricercatori che si sono interessati all’uno o all’altro fenomeno hanno generalmente sottolineato le specificità del loro oggetto di studio piuttosto che le caratteristiche comuni. Per quanto riguarda le piattaforme istituzionali, l’attenzione si è concentrata principalmente sulla standardizzazione e strutturazione dei dati prodotti o sulle questioni legali ed etiche. Al contrario, i lavori che si interessano alle piattaforme amatoriali (nel contesto degli studi sui fan, sulla cultura partecipativa, sulla produzione artistica dilettante, ecc.) prestano maggiore attenzione alle dinamiche di costruzione dei profili, agli stili di scrittura e alle pratiche digitali e sociali della notorietà.

Tuttavia, è interessante provare a superare questa opposizione e studiare la circolazione tra i diversi spazi digitali. Rifiutando l’idea di una piattaforma come un dispositivo digitale isolato e separato dagli altri, proponiamo di considerare la piattaforma collaborativa come un ecosistema “multi-spaziale”. Con il termine “piattaforma culturale collaborativa”, facciamo riferimento a qualsiasi dispositivo digitale che permette al pubblico di contribuire alla costruzione della conoscenza relativa a degli oggetti culturali in collaborazione con una o più istituzioni culturali. Questa definizione non vuole includere solo il caso di dispositivi digitali creati e gestiti da un’istituzione, ma anche le iniziative spontanee e auto-organizzate (che si basano su strumenti collaborativi esistenti come Wikipedia, su piattaforme commerciali o sui social), per creare uno spazio espressivo informale in connessione con una piattaforma istituzionale. Queste piattaforme cross-mediali forniscono diversi spazi digitali, adattati alle esigenze delle istituzioni e dei dilettanti, che permettono la scrittura collaborativa di più persone appartenenti a diversi mondi sociali. Possiamo citare l’esempio del progetto 1 Jour 1 Poilu (1 Giorno 1 Soldato) che collega la piattaforma istituzionale Mémoire des Hommes (gestita dal Ministero della Difesa), un hashtag Twitter, una pagina e un gruppo Facebook (Severo, 2021)

Piattaforme cross-mediali

Una definizione cross-mediale di piattaforma collaborativa permette di valorizzare gli scambi tra persone e di contenuto da uno spazio digitale all’altro, mettendo l’accento sull’impatto delle affordances di ogni spazio sulla struttura partecipativa. L’incontro tra istituzione e dilettante avviene con metodi e obiettivi diversi a seconda dello spazio che lo ospita. Ogni dispositivo fornisce un quadro funzionale alla creazione di legami sociali. Il termine ‘collaborativo’, piuttosto che quello di ‘partecipativo’, mira precisamente a sottolineare l’impegno di diversi attori nella scrittura e la possibilità che diverse definizioni possano coesistere. Il termine ‘partecipativo’, con il suo potere più inglobante, tende invece a identificare piattaforme in cui la partecipazione rimane passiva e non corrisponde a un reale coinvolgimento attivo del pubblico. In conclusione, una piattaforma collaborativa non dovrebbe essere concepita come un sito web o un sistema informativo isolato, ma come un facilitatore di dialogo tra attori sociali che può dispiegarsi anche in spazi digitali non istituzionali, come i social.

_____________________

Per approfondire

- Jenkins, H., M. Ito, and D. Boyd. Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015.

- Leadbeater, C, P. Millet. The Pro-Am Revolution: How Enthousiasts are changing our Economy and Society. London: Demos, 2004.

- Severo, M. L’impératif participatif. Paris: INA Editions, 2021.

Siti web

- Europeana Transcribe: https://europeana.transcribathon.eu/ (last accessed 10 December 2021).

- Défi collaboratif: https://www.1jour1poilu.com/ (last accessed 10 December 2021).

- ANR Collabora: https://anr-collabora.parisnanterre.fr/index.php/the-project/ (last accessed 10 December 2021).

_____________________

Crediti d’immagine

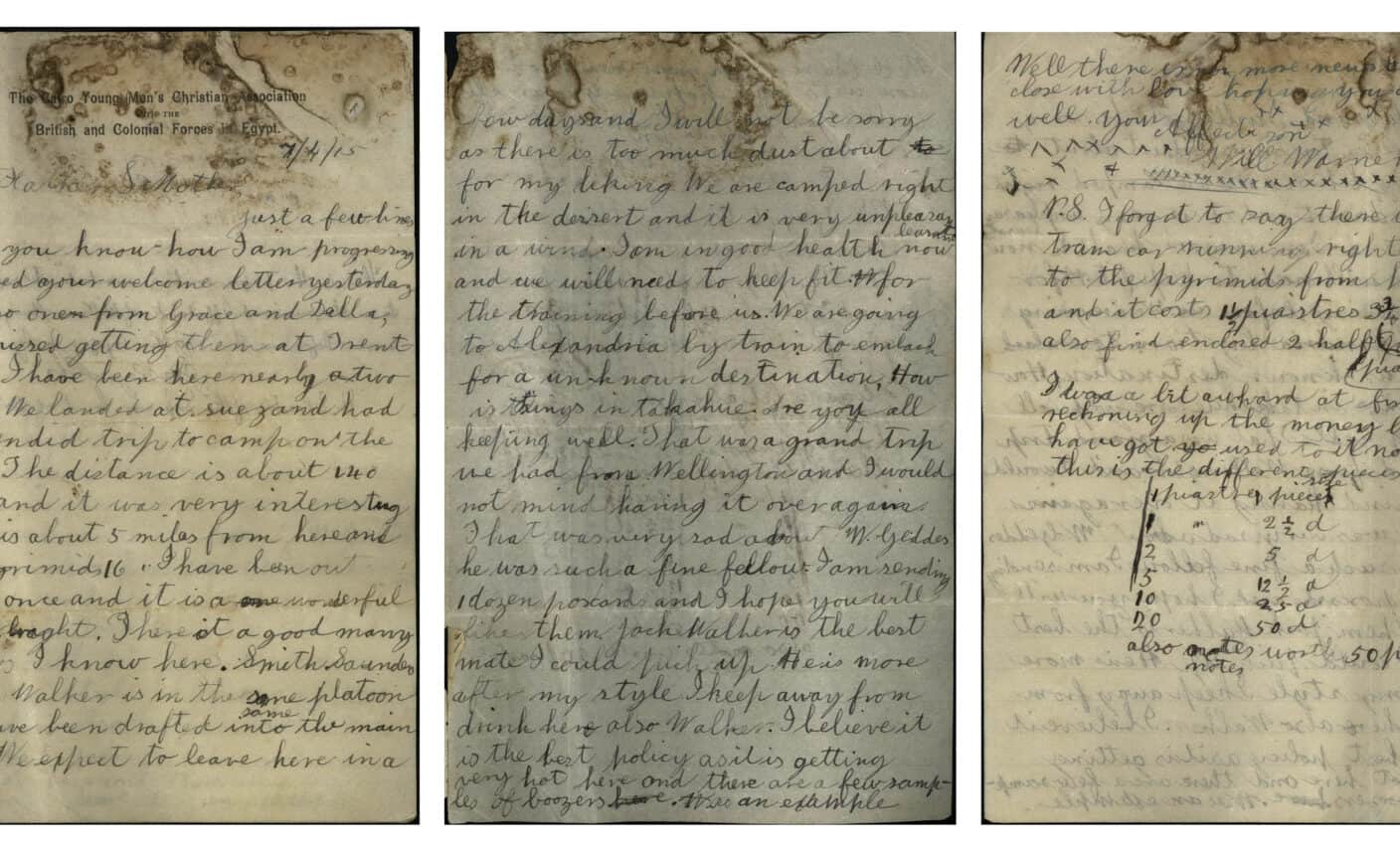

Letter from William Henry Warner (WW1 Soldier) to his parents – April 1915 © CC BY-SA 2.0 Archives New Zealand via Commons.

Citazione raccomandata

Severo, Marta: Collaborative Platforms: Cultural Heritage and Participation. In: Public History Weekly 10 (2022) 1, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-19327.

Responsabilità editoriale

Citizen participation in cultural heritage is particularly facilitated in the digital ecosystem by collaborative platforms. But there are substantial differences between amateur and institutional environments. Neither is neutral: in the former, participation is conditioned by political/ideological visions, in the latter by scientific protocols.

Digital Ecosystems

In recent years, citizen participation has increased considerably in fields as diverse as politics, economics, media, and culture. From participatory democracy to collaborative economy, from crowdsourcing to civic techs, these new forms of political, economic, and technological organization are currently changing our society. Digital technologies have boosted this trend by offering new possibilities for expression and by functioning as a lever for innovation. Furthermore, the diffusion of the digital culture, beyond the tools themselves, has confirmed a shift which now stresses the empowerment of citizens, made possible by digital technologies and the creative expression of individual freedom.

In this spirit of ‘ubiquitous participation’, the sector of cultural heritage as well has been confronted with the phenomenon of rapid transformation based on participant involvement. One of the main effects has been the explosion of digital collaborative platforms, i.e. digital environments that allow contributors, also called amateurs, to express themselves by posting or commenting on content about their cultural objects. The web, first with blogs and other web 2.0 tools and then with social networks and crowdsourcing platforms, has enabled pro-amateurs to share and disseminate their knowledge to as many people as possible in new spaces based essentially on the democratization of expressive possibilities. Comping with this new trend, several institutions started to use this kind of tool in order to allow citizen participating to their activities. More than ever, collaborative platforms (whether institutional, commercial or associative) are seen as vectors of new forms of engagement, sharing and dissemination of knowledge in the field of cultural heritage.

Scientific research around this object tend to identify and describe two opposite phenomena: on the one hand, amateur platforms and on the other, institutional platforms. This paper will briefly present these two research directions and in the last part, it will argue the interest of overpassing this opposition in order to fully understand the impact of this phenomenon in the cultural heritage sector.

Amateurs

Amateur platforms are digital initiatives carried out spontaneously by groups of amateurs, artists or fans, who can rely on commercial (e.g. Soundcloud, YouTube, etc.) or associative devices (e.g. Wikipedia). These devices offer two main affordances for amateurs: the possibility of building their digital identity and increasing their e-reputation; and the opportunity of expressing themselves through writing and editorialisation.

The digital platform that has attracted enthusiasts the most is undoubtedly Wikipedia. Wikipedia ranks first, both for the mass of created content in a participatory manner or for the number of contributors who take part in this adventure. Launched in 2001, this web space brings together today (October 2021) more than 40 million articles and more than 16,000 active editors only for the English version. Compared to other initiatives, its peculiarity is its general nature: it is considered the first online encyclopedia. Its contents have to be neutral, supported by sources and not original, as the contents of an encyclopedia.

Beyond Wikipedia, thousands of other platforms have been created (and often have already disappeared) to meet the needs of amateurs, artists or fans, in a specific field. For music, we can cite the sites of creation and self-promotion of artists such as MySpace or SoundCloud (as well as those of consumption, in particular streaming listening platforms such as Spotify. When it comes to photography, the artist and the fan often overlap. On Flickr folksonomies have emerged as tools of sociability and social structuring. If we consider the world of literature, we must distinguish platforms designed for authors like Wattpad from those devoted to critics like Goodreads. The attention of researchers working on these amateur platforms is shifting more and more, abandoning the study of contributors’ practices to focus on platform policies. Far from being neutral spaces of expression, these platforms determine not only the writing styles of amateurs, but also their impact on the cultural sector through their classification algorithms.

Institutional Platforms

In the institutional context, the term ‘collaborative platform’ most of the time identifies a digital device (made available by an institution) where the non-professional voluntary contributor can participate to the construction of knowledge related to cultural objects managed by the institution. The diffusion of these platforms is strictly related to the recent success of citizen science, a scientific movement aimed at integrating citizens into the processes of construction of scientific knowledge. These institutional platforms have developed alongside amateur platforms as a completely autonomous phenomenon. Indeed, cultural institutions prefer to build ad hoc platforms rather than rely on pre-existing systems. Amateur platforms do not seem suited to the scientific objectives of institutions and don’t seem to guarantee the necessary quality standards. It then becomes necessary to build institutional platforms that can make it possible to engage the amateur according to institutional requirements.

Many institutions have launched citizen science applications. This is the case of the projects hosted on the Zooniverse platform, in particular the AnnoTate project which makes it possible to transcribe artists’ documents kept in the Tate archives, or the Shakespeare’s World project which offers the chance to transcribe handwritten documents from Shakespeare’s contemporaries (1564-1616). In addition, the main international libraries have their transcription portal, for example the British Library has many projects on LibCrowd. Likewise, Europeana, which brings together resources from cultural institutions from all over Europe, has opened its participatory section on the Europeana Transcribe site devoted to documents from the First World War.

The most popular institutional collaborative tool is the crowdsourcing, i.e. a tool that allows the public to perform simple tasks, such as transcribing handwritten texts or indexing documents, to help the institution to build databases on cultural heritage, useful for its safeguard. The main objective of crowdsourcing platforms is to produce standardized data that can be integrated into the institution’s databases. Many municipal and departmental archives have launched collaborative indexing projects. For example, the French National Archives launched in 2018 the Testaments de Poilus project, a platform where amateurs can transcribe the wills of the soldiers of the Great War. Through this device, not only do volunteers transcribe, but also, they encode documents in TEI (Markup Format for Textual Records) format. Even if the task is very demanding, the institution does not even have time to publish new documents that they are already transcribed. Moreover, transcriptions are generally validated by other volunteers, without the need for intervention by the professionals. All these institutional platforms have in common the fact that they define a top-down protocol that standardizes the participation of the amateur in order to guarantee the scientific quality of the contributions.

Crossing Amateur and Institutional Perspectives

Amateur and institutional platforms have rarely been linked. Researchers who have been interested in one or the other phenomenon have generally emphasized the specificities of their study object rather than the common features. Regarding institutional platforms, attention is mainly focused on the standardization and structuring of data produced or on the legal and ethic issues. On the contrary, works that are interested in amateur platforms (in the context of studies on fans, on participatory culture, on amateur artistic production, etc.) are paying more attention to profile building, to the writing styles and the digital and social dynamics of notoriety.

Yet, we argue the interest of overpassing this opposition and study the circulation between different digital spaces. By rejecting the idea of a platform as an isolated digital environment separate from others, we propose to consider the collaborative platform as a multi-space environment. With the term ‘cultural collaborative platform’, we refer to any digital environment that allows audiences to contribute to the construction of knowledge related to cultural objects in interaction with one or more cultural institutions. This definition does not only aim to include the case of digital devices created and managed by an institution, but also spontaneous and self-organized initiatives that can rely on existing collaborative tools such as Wikipedia or even on commercial platforms or social media, to create a wider space for exchange in connection with an institutional platform. These cross-media platforms provide several digital spaces, adapted to the needs of institutions and amateurs, which allow collaborative writing by several people belonging to different social worlds. We can cite the example of the 1 Jour 1 Poilu (1 Day 1 Soldier) project which links the institutional platform Mémoire des Hommes (managed by the Ministry of Army), a twitter hashtag, a Facebook page and a Facebook group (Severo, 2021).

The interest of a cross-media definition is to follow the exchanges between people and their contributions from one digital space to another by placing the emphasis on the impact of the affordances of each space on the participatory structure. The meeting between institution and amateur takes place with different methods and objectives depending on the space where it takes place. Each space provides a functional framework for successful bonding. The term ‘collaborative’, rather than that of ‘participatory’, precisely aims to underline the engagement of different actors in the writing and the possibility that several definitions can coexist. The term ‘participatory’, with its more encompassing power, also tends to identify platforms where participation remains passive and does not correspond to a real active contribution from the public. Thus, in our view, a collaborative platform should not be designed as a single website or as a single information system, but as a facilitator of dialogue between social actors that can occupy also non-institutional spaces, such as social media.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Jenkins, H., M. Ito, and D. Boyd. Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015.

- Leadbeater, C, P. Millet. The Pro-Am Revolution: How Enthousiasts are changing our Economy and Society. London: Demos, 2004.

- Severo, M. L’impératif participatif. Paris: INA Editions, 2021.

Web Resources

- Europeana Transcribe: https://europeana.transcribathon.eu/ (last accessed 10 December 2021).

- Défi collaboratif: https://www.1jour1poilu.com/ (last accessed 10 December 2021).

- ANR Collabora: https://anr-collabora.parisnanterre.fr/index.php/the-project/ (last accessed 10 December 2021).

_____________________

Image Credits

Letter from William Henry Warner (WW1 Soldier) to his parents – April 1915 © CC BY-SA 2.0 Archives New Zealand via Commons.

Recommended Citation

Severo, Marta: Collaborative Platforms: Cultural Heritage and Participation. In: Public History Weekly 10 (2022) 1, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-19327.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright (c) 2019 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 10 (2022) 1

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-19327

Tags: Collaboration, Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), Language: Italian, Wikipedia

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Scope for further Revision

Marta Severo’s contribution on “collaborative platforms” in Cultural Heritage is a thought-provoking, if fairly preliminary and self-limited, typology and analysis of how “citizen participation” occurs in Open Science projects.

By “citizen participation,” Severo means projects such as Galaxy Zoo, in which the general public is asked to help identify galaxy shapes and forms in images from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, or the AnnoTate project, in which the goal is to crowd source transcriptions of artists’ documents from the Tate Museum. While the subject of these projects and the precise actions required of participants is often very different the basic process involved is quite similar, and, indeed, they often use the same or similar infrastructure (e.g. Zooiverse, or, I suppose given the argument of the article, Media Wiki): data (telescope photographs, satellite images, facsimiles of historical documents) are published via the selected platform and the public is invited to do something that (initially at least) requires human intelligence to carry out — recognise and classify shapes, characterise forms, or transcribe texts. In some cases, this input is used to train Artifical Intelligence to do further work; in others it is data intended solely for further analysis.

The projects discussed in the previous paragraph are all “professional” in the sense that they are run by professional researchers in the service of some kind of university- or other institution-based research project. But other projects also involve citizen participation, even if they aren’t run by professional (or at least cultural or scientific-institution-based) researchers. An obvious example is the Wikipedia, which has developed an extremely large and generally high quality reference resource entirely through crowdsourcing. This, Severo argues, can also be said for platforms like SoundCloud, Flikr, MySpace, or even Spotify. These “amateur platforms” too, she says, involve “citizen participation” and really should be considered as part of the same movement represented by “Institutional platforms” such as Zooiverse or Museum crowdsourcing platforms.

Severo proposes calling these platforms and activities “cultural collaborative platforms,” defining the term to mean “any digital environment that allows audiences to contribute to the construction of knowedge related to cultural objects in interaction with one or more cultural institutions.” The goal, she argues, is to recognise that the point of all, whether “amateur” or “institutional” or a combination of the two, is to serve as a “facilitator or dialgoue between social actors.”

I have mixed views on the success of Severo’s argument. On the one hand, I think she is right to argue that there is a commonality to citizen-science efforts like GalaxyZoo and the Wikipedia that is useful and important to recognise. But on the other, I find it a stretch to extend that concept to sites like SoundCloud or (to a lesser extent) FLikr and (to a much greater extent) Spotify.

The issue is “the construction of knowledge.” While I am sure that there are some Flikr sites dedicated to collecting images on a certain subject (something even more true of Pinterest), they are almost certainly the exception rather than the rule: the point of most of the platforms that Severo cites on the amateur side of things is less to construct a body of knowledge or data than to build a canon of (mostly original) content for consumption by others: original music (Soundcloud and, to the degree it is participatory, Spotify), or original photography (Flikr). This seems to me to be fundamentally different from what’s going on in GalaxyZoo and Wikipedia.

One interesting border-line case that Severo doesn’t mention is fanfiction: these are like Flikr and Soundcloud in that they are about the generation and dissemination of original content, but they are like “cultural collaborative platforms” in that the “fans” are collectively filling in a canonical world based on the original texts.

Without a stronger recognition of the essential requirement that such sites contribute to the “construction of knowledge,” it seems to me that Severo runs the risk of conflating basically any Participatory Web 2.0 technology with the Wikipedia and GalaxyZoo. This would vitiate the entire point of her article.

I think there is a very interesting point here and that the quest for a cross-institutional definition of “cultural collaborative platforms” is very worthwhile. But I don’t think the article as a whole pulls this argument off completely and I believe that there’s scope for further revision.