Abstract: Historic monuments are making the news. The removal of American Civil War Confederacy leaders’ statues by a local council in Baltimore has provoked reaction from the U.S. President. Closer to (my) home, within the same fortnight, news that vandals had defaced the Captain Cook statue that stands in Hyde Park, Sydney, garnered attention from both the Australian Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. These back-to-back events have raised questions in the public sphere about monuments as history.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10215.

Languages: English, Deutsch

Historic monuments are making the news. The removal of American Civil War Confederacy leaders’ statues by a local council in Baltimore has provoked reaction from the U.S. President. Closer to (my) home, within the same fortnight, news that vandals had defaced the Captain Cook statue that stands in Hyde Park, Sydney, garnered attention from both the Australian Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. These back-to-back events have raised questions in the public sphere about monuments as history.

White supremacy in stone?

U.S. President Trump’s opposition to the removal of the statues of pro-slavery Civil War Confederate commander Robert E. Lee and Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson from a park in Baltimore (USA) has made headlines.[1] The removal of the statues was reported to be the council’s response to “acts of domestic terrorism,”[2] a reference to the car-ramming attack by a white supremacist against anti-racism protestors in Charlottesville, Virginia a few days earlier. The act had claimed the life of one person and injured many others.[3] It should be noted that a longer history of debate had shrouded the future of these monuments, and a Baltimore City commission had recommended their removal months earlier.[4]

According to news media in the wake of the Charlottesville attack, Councilman Brandon Scott called for these statues “not just to be moved, but also destroyed.”[5] For Scott, the continued presence of Confederate statues in public parks operated as a signal to white supremacist groups that their racist attitudes and behavior was sanctioned by the state. Removing these statutes, agreed unanimously by the members of Baltimore City Council, therefore aimed to communicate an entirely different message: the rejection of the discourse of racism and the violence that often arises with it.[6] Interestingly, and perhaps worth noting, the Jackson and Lee Monument, commemorating the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863, was not an immediate post-Civil War creation, but the work of Laura Gardin Fraser, unveiled for the first time in 1948.[7]

No pride in monuments

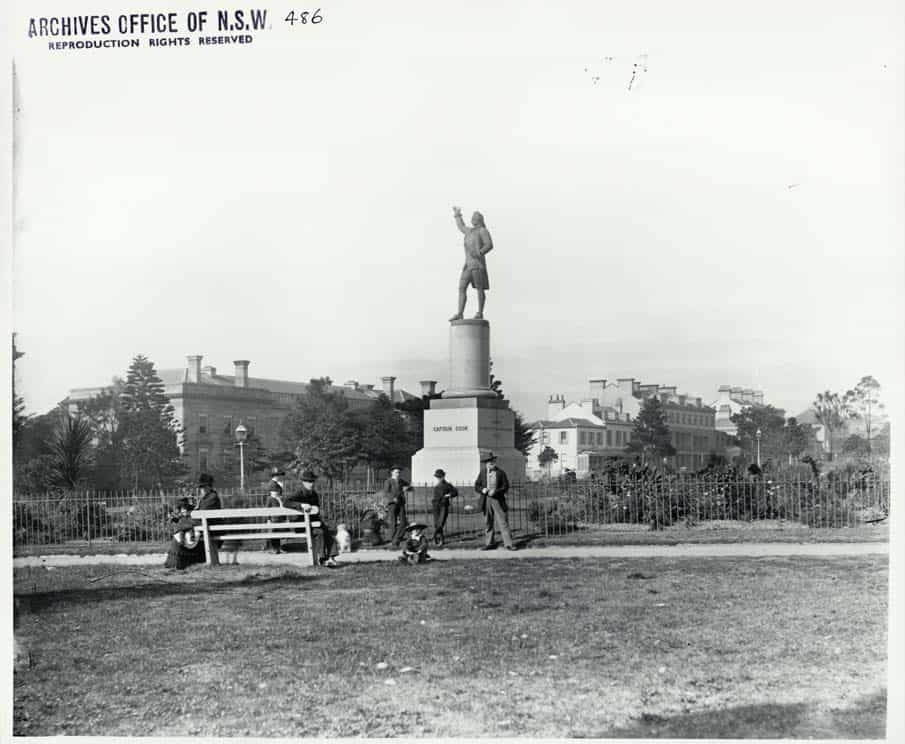

On 26 August this year, Sydney residents awoke to the defacement of Hyde Park’s statues of Captain Cook and Lachlan Macquarie (fifth governor of the colony of New South Wales). The Cook monument proclaims him as the man who “discovered this territory” in 1770. The graffiti on the main face of the base proclaimed “no pride in genocide” (making Cook the symbol of the European Colony that followed). On a second face was written “change the date” (in an appeal to shift Australia Day away from its association with the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet on 26 January 1788, a day of sorrow rather than celebration for Indigenous Australians).[8] Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull reacted to the vandalism by describing the graffiti as an act of Stalinism, where opponents “became non-persons, banished not just from life’s mortal coil but from memory and history itself.”[9]

Turnbull’s lament about the treatment of two of Australia’s “heroes” by reference to Stalin and his erasure of political opponents from the historical record is, of course, a selective use of history, given Stalin was not a member of a repressed minority protesting an official history, but the person with the power to create one. However, as with other sorties in what are arguably Australia’s on-going “history wars”, the Prime Minister’s comments provoked reaction from both sides of politics, the Leader of the Opposition calling for an alternative plaque to be placed next to the one from 1879,[10] which would honour, one assumes, indigenous perspectives on the past. When the Captain Cook monument was unveiled on 25 February 1879, one hundred years after Cook’s death, over 40,000 people were estimated to be in attendance, marking it as a significant event of the period.[11]

The monument as a text

Like all “texts”, the meaning of monuments is obviously open to interpretation. Historic monuments exist with an inherent ambiguity, commemorating a past (that in the cases above was already remote), but also documenting something about the history culture of the time in which they were created.[12] Our reactions in the present, of course, then reveal just as much about our own history culture and the discourses that circulate within it. When they stand in a park, their meaning is unclear. Are they there to caution or celebrate, to provoke or proclaim? This raises questions for the public historian about how we should react. Surely it is an act of vandalism to destroy controversial monuments because they provoke contemporary sensibilities, as many declared when the Taliban destroyed 1,700 year old sandstone Buddhas carved into a cliff in the Bamiyan Valley in central Afghanistan?[13]

Yet where are the limits? I am sure there are historical figures whose monuments we would not tolerate. The removal of statues of this kind clearly makes for powerful symbolic statements, as was seen in what appears to have been the orchestrated toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein.[14]

The monument in the museum?

For Nietzsche[15], there were three forms of historical discourse: the monumental (in which great events and deeds serve as models for the present), the antiquarian (that attempts to preserve the past as cultural heritage and source of identity), and the critical (in which the past is challenged and interrogated from the standpoint of contemporary wisdom). I confess to a sympathy for Nietzsche’s concerns that any one form of historical discourse in excess, or at the exclusion of others, leads to paralysis in the present, denying us a source of identity, or trapping us within one.

This provokes me to ask: Are there ways to interpolate or interrupt the monument “in the wild” so to speak (juxtaposing the critical against the monumental and antiquarian interests statues often embody)? Where possible, should controversial monuments be moved to museums, where the controversies around their existence can be named much like the Australian National Museum has done online in discussing its controversial exhibits?[16] Should new statues dedicated to those rendered historically invisible be erected alongside or nearby the offending monuments?[17] Do we need appendices to the plaques on these monuments, that offer “interpretive frames” for the viewing public, that reflect contemporary critical historical perspectives and are juxtaposed with the original inscriptions, effectively reframing the monument as an artefact in an open air museum?

Regardless of our answers to these questions, one can be certain that whatever we do in relation to the problem of monuments will say as much about ourselves, as about those who erected the monuments in the first place.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Davison, Graeme. “A historian in the museum: The ethics of public history.” In Stuart Macintyre (Ed.). The historian’s conscience: Australian historians on the ethics of history (pp. 49-63). Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2004.

- Levinson Sanford. Written in stone: Public monuments in changing societies. Duke University Press: Durham and London, 1998.

- Simon, Roger I.. “The terrible gift: Museums and the possibility of hope without consolation.” Museum Management and Curatorship, 21 no. 3 (2007): 187–204.

Web Resources

- Bershidsky, Leonid. “Let Artists Put Controversial Monuments in a New Light.” Bloomberg: Opinion (28 August 2017), https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-08-28/let-artists-put-controversial-monuments-in-a-new-light (last accessed 14 September 2017).

- Grant, Stan. “America tears down its racist history, we ignore ours.” ABC News (20 August 2017), http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-18/america-tears-down-its-racist-history-we-ignore-ours-stan-grant/8821662 (last accessed 13 September 2017).

- Schedler, George. “Are Confederate monuments racist?” International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 15 no.2 (2001): 287–30.

_____________________

[1] Reuters. Donald Trump sad to see “beautiful” Confederate statues torn down after Charlottesville violence. ABC News (18 August 2017), http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-18/donald-trump-sad-to-see-beautiful-statues-torn-down/8818228 (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[2] Fern Shen. Council resolves “to deconstruct” Confederate monuments. Baltimore Brew (15 August 2017), https://baltimorebrew.com/2017/08/15/council-resolves-to-deconstruct-confederate-monuments/ (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[3] ABC/AP. “Charlotesville: At least one dead as car ploughs into protesters at white supremacist rally in Virginia.” ABC News (13 August 2017), http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-13/car-ploughs-into-crowd-at-white-nationalist-rally/8801390 (last accessed 13 September 2017)

[4] Luke Broadwater. “Baltimore City commission recommends removal of two Confederate monuments.” The Baltimore Sun (14 January 2016), http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/baltimore-city/bs-md-ci-confederate-monuments-20160114-story.html (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[5] ABC/Reuters. “Charlottesville: Baltimore’s Confederate monuments removed overnight after violence.” ABC News (17 August 2017), http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-17/confederate-monuments-in-baltimore-removed-overnight/8814442 (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[6] Gina Cherelus. “Baltimore removes four Confederate statues after Virginia rally.” Reuters (16 August 2017), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-virginia-protests-statues-baltimore/baltimore-removes-four-confederate-statues-after-virginia-rally-idUSKCN1AW115 (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[7] Dennis Hengeveld. “The Life and Work of Laura Gardin Fraser.” Coin Update (18 July 2014), http://news.coinupdate.com/the-life-and-work-of-laura-gardin-fraser-3389/ (last accessed 14 September 2017).

[8] Amy Remeikis. “‘An additional plaque’: Bill Shorten’s plan to neutralise Captain Cook debate.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 August 2017, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/an-additional-plaque-bill-shortens-plan-to-neutralise-captain-cook-debate-20170828-gy5ioc.html (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[9] Michael Kozlol. “Vandalism of Hyde Park statues is a ‘deeply disturbing’ act of Stalinism,” says Malcolm Turnbull. The Sydney Morning Herald (26 August 2017), http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/vandalism-of-hyde-park-statues-is-a-deeply-disturbing-act-of-stalinism-says-malcolm-turnbull-20170826-gy4vmn.html (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[10] Amy Remeikis (2017), above.

[11] Geoff Barker (2017). Unveiling of Captain Cook’s Statue, Hyde Park, Sydney. Research and Discovery, State Library of New South Wales, http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/blogs/unveiling-captain-cooks-statue-hyde-park-sydney (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[12] The following article does a good job of outlining many of the mnemonic possibilities of objects in the museum: Graham Black. (2011), “Museums, memory and history,” Cultural and Social History: The Journal of the Social History Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 415-427. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/147800411X13026260433275 (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[13] Ahmen Rashid. “After 1,700 years, Buddhas fall to Taliban dynamite.” The Telegraph (12 March 2001), http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/afghanistan/1326063/After-1700-years-Buddhas-fall-to-Taliban-dynamite.html (last accessed 14 September 2017).

[14] Max Fischer. “The Truth About Iconic 2003 Saddam Statue-Toppling: ProPublica/New Yorker investigation finds the media got it wrong.” The Atlantic (3 January 2011), https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/01/the-truth-about-iconic-2003-saddam-statue-toppling/342802/ (last accessed 13 September 2017); and Peter Maass. “The Toppling: How the media inflated a minor moment in a long war.” The New Yorker (10 January 2011), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/01/10/the-toppling (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[15] Friederich Nietzsche. (1874/1983). “On the uses and disadvantages of history for life” (trans. by R. J. Hollingdale) Untimely meditations (pp. 57–123). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[16] See, for example, the discussion of the controversial Bells Falls Gorge exhibit on the Australian National Museum’s website: http://www.nma.gov.au/education/resources/multimedia/interactives/bells_falls_gorge_html/why_is_the_display_controversial (last accessed 14 September 2017).

[17] Katie Pavlich. “A solution to the monument controversy: Build new statues dedicated to minorities in American history.” Townhall (16 August 2017), https://townhall.com/tipsheet/katiepavlich/2017/08/16/a-solution-to-the-monument-controversy-build-new-monuments-dedicated-to-minorities-in-american-history-n2369601 (last accessed 14 September 2017).

_____________________

Image Credits

© Oxyman. Statue of Captain Cook in Hyde Park, Sydney. Dated: after 25 Feb 1879 via flickr.

Recommended Citation

Parkes, Robert: Are Monuments History? In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 34, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10215.

Historische Denkmäler machen Schlagzeilen. Die Abschaffung der Statuen von verschiedenen Führern der Konföderation im amerikanischen Bürgerkrieg durch einen Gemeinderat in Baltimore hat US-Präsident Trump auf den Plan gerufen. In meiner Heimatstadt erlebte ich innerhalb derselben vierzehn Tage, wie Vandalen die Statue des Captain Cook, die im Hyde Park in Sydney steht, entstellten und sowohl die Aufmerksamkeit des australischen Premierministers als auch des Oppositionsführers erregten. Diese aufeinander folgenden Ereignisse haben in der Öffentlichkeit Fragen zu Denkmälern als Geschichte aufgeworfen.

Weiße Vorherrschaft aus Stein?

US-Präsident Trumps Widerstand gegen die Entfernung der Statuen der Konföderierten-Generale Robert E. Lee und Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, beide Sklaverei-Befürworter, aus einem Park in Baltimore (USA) hat Schlagzeilen gemacht.[1] Die Entfernung der Statuen soll die Reaktion des Stadtrates auf “Akte des inländischen Terrorismus”[2] gewesen sein, ein Verweis auf den Autoangriff eines weißen Rassisten auf Anti-Rassismus-Demonstranten in Charlottesville, Virginia, wenige Tage zuvor. Die Tat hatte ein Todesopfer gefordert und viele andere verletzt.[3] Es sei darauf hingewiesen, dass eine längere Geschichte der Debatte die Zukunft dieser Denkmäler vorausgegangen war, und dass eine Kommission der Stadt Baltimore ihre Entfernung bereits einige Monate zuvor empfohlen hatte.[4]

Nach dem Anschlag von Charlottesville forderte Stadtrat Brandon Scott, dass diese Statuen “nicht nur entfernt, sondern auch zerstört werden sollten.”[5] Für Scott diente die fortwährende Präsenz von konföderierten Statuen in öffentlichen Parks als Signal für rechtsextreme Gruppen, dass ihre rassistische Haltung und ihr rassistisches Verhalten staatlich sanktioniert wurden. Die Entfernung dieser Statuen, einstimmig von den Mitgliedern des Stadtrates von Baltimore beschlossen, sollte daher eine völlig andere Botschaft vermitteln: die Ablehnung des Rassismusdiskurses und der damit häufig verbundenen Gewalt.[6] Interessanterweise, und vielleicht auch bemerkenswerterweise, war das Jackson and Lee-Denkmal, das an die Schlacht von Chancellorsville im Jahre 1863 erinnert, keine unmittelbare Nachbürgerkriegsschöpfung, sondern das Werk von Laura Gardin Fraser, das 1948 zum ersten Mal enthüllt wurde.[7]

Kein Stolz auf Denkmäler

Am 26. August dieses Jahres erwachten die EinwohnerInnen Sydneys mit der Verunstaltung der Statuen von Captain Cook und Lachlan Macquarie (fünfter Gouverneur der Kolonie von New South Wales) im Hyde Park. Das Denkmal lobpreist Cook als den Mann, der 1770 dieses Territorium “entdeckte”. Die Graffiti auf der Vorderseite des Sockels verkündeten “Seid nicht stolz auf Völkermord” (was Cook zum Symbol der nachfolgenden europäischen Kolonie machte). Auf einem zweiten Fläche des Sockels stand geschrieben: “Ändert das Datum” (ein Appell, den Australia Day von seinem Bezug zum Jahrestag der Ankunft der Ersten Flotte am 26. Januar 1788, einem Tag der Trauer statt der Freude für die indigene Bevölkerung Australiens, wegzuverlegen).[8] Der australische Premierminister Malcolm Turnbull reagierte auf den Vandalismus, indem er die Graffiti als einen Akt des Stalinismus bezeichnete, bei dem GegnerInnen “zu Unpersonen wurden, die nicht nur aus der sterblichen Spirale des Lebens, sondern auch aus dem Gedächtnis und der Geschichte selbst verbannt wurden”[9].

Turnbulls Klage über die Behandlung von zwei australischen “Helden” durch Bezugnahme auf Stalin und dessen Löschung von politischen GegnerInnen aus historischen Aufzeichnungen ist natürlich eine selektive Verwendung von Geschichte, da Stalin nicht einer unterdrückten Minderheit angehörte, die gegen offizielle Geschichte protestierte, sondern die Macht hatte, eine solche Geschichte zu schaffen. Doch wie bei anderen Einsätzen in den anhaltenden “history wars” Australiens löste der Premierminister Reaktionen in beiden politischen Lagern aus. So forderte der Oppositionsführer, dass eine alternative Gedenktafel neben jener von 1879 [10] gestellt werden sollte, die, so wurde vermutet, die indigene Sichtweisen auf die Vergangenheit ehren würde. Als am 25. Februar 1879, einhundert Jahre nach seinem Tod, das Denkmal von Kapitän Cook enthüllt wurde, waren schätzungsweise über 40.000 Menschen anwesend, was es zu einem bedeutenden Ereignis jener Zeit machte.[11]

Das Denkmal als Text

Wie alle “Texte” ist auch die Bedeutung von Denkmälern ebenfalls Gegenstand der Interpretation. Historische Denkmäler existieren mit einer inhärenten Mehrdeutigkeit, die an eine Vergangenheit erinnert (die in den obigen Fällen bereits weit entfernt war), aber auch etwas über die Geschichtskultur der Zeit, in der sie entstanden sind, dokumentiert.[12] Unsere Reaktionen in der Gegenwart offenbaren dann natürlich ebenso viel über unsere eigene Geschichtskultur und die darin zirkulierenden Diskurse. Wenn sie in einem Park stehen, ist ihre Bedeutung unklar. Sind sie da, um zu warnen oder zu feiern, zu provozieren oder zu proklamieren? Das wirft für Public Historians Fragen auf, wie wir reagieren sollen. Es ist sicherlich ein Akt des Vandalismus, umstrittene Denkmäler zu zerstören, weil sie zeitgenössische Befindlichkeiten provozieren, daran waren sich viele Leute einig, als die Taliban 1700 Jahre alte Sandstein-Buddhas zerstörten, die in eine Klippe im Bamiyan-Tal in Zentralafghanistan gehauen wurden.[13]

Doch wo sind die Grenzen? Ich bin sicher, es gibt historische Persönlichkeiten, deren Denkmäler wir nicht tolerieren würden. Die Entfernung solcher Statuen führt eindeutig zu mächtigen symbolischen Aussagen, wie man an dem vermeintlich orchestrierten Umstürzen der Saddam-Hussein-Statue sieht.[14]

Das Denkmal im Museum?

Für Nietzsche[15] gab es drei Formen des historischen Diskurses: das Monumentale (in dem große Ereignisse und Taten als Vorbilder für die Gegenwart dienen), das Antiquarische (das versucht, die Vergangenheit als kulturelles Erbe und Identitätsquelle zu bewahren) und das Kritische (in dem die Vergangenheit vom Standpunkt der zeitgenössischen Weisheit herausgefordert und befragt wird). Ich muss meine Sympathie für Nietzsches Anliegen bekennen, dass jede Form des historischen Diskurses, die exzessive Züge aufweist oder unter Ausschluss anderer geschieht, zu einer Lähmung in der Gegenwart führt, indem sie uns eine Quelle der Identität vorenthält oder uns darin einfängt.

Dies führt mich zu einer provokanten Frage: Gibt es Möglichkeiten, das Monument sozusagen “in der Wildnis” zu interpolieren oder zu unterbrechen (d.h. kritische Interessen monumentalen und antiquarischen gegenüberzustellen, die Statuen ja oft verkörpern)? Sollten umstrittene Denkmäler womöglich in Museen verlegt werden, wo die Kontroversen um ihre Existenz so benannt werden können, wie es das Australian National Museum online getan hat, als es seine umstrittenen Exponate diskutierte?[16] Sollen neben oder in der Nähe der anstößigen Monumente neue Statuen errichtet werden, die den historisch unsichtbaren Menschen gewidmet sind?[17] Sollten die Gedenktafel dieser Monumente mit Anhängen versehen werden, die der Öffentlichkeit einen “interpretativen Rahmen” bieten, die die zeitgenössische kritische historische Perspektive reflektieren und den Originalinschriften gegenübergestellt werden, und dadurch das Monument als Artefakt in einem Freilichtmuseum neu gestalten?

Unabhängig von unseren Antworten auf diese Fragen kann man sicher sein, dass alles, was wir im Zusammenhang mit dem Problem der Denkmäler tun, genauso viel über uns selbst aussagen wird wie über diejenigen, die die Denkmäler überhaupt errichtet haben.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Davison, Graeme. “A historian in the museum: The ethics of public history.” In Stuart Macintyre (Ed.). The historian’s conscience: Australian historians on the ethics of history (pp. 49-63). Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2004.

- Levinson, Sanford. Written in stone: Public monuments in changing societies. Duke University Press: Durham and London, 1998.

- Simon, Roger I.. “The terrible gift: Museums and the possibility of hope without consolation.” Museum Management and Curatorship, 21 no. 3 (2007): 187–204.

Webressourcen

- Bershidsky, Leonid. “Let Artists Put Controversial Monuments in a New Light.” Bloomberg: Opinion (28 August 2017). Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-08-28/let-artists-put-controversial-monuments-in-a-new-light (last accessed 14 September 2017).

- Grant, Stan. “America tears down its racist history, we ignore ours.” ABC News (20 August 2017). Available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-18/america-tears-down-its-racist-history-we-ignore-ours-stan-grant/8821662 (last accessed 13 September 2017).

- Schedler, George. “Are Confederate monuments racist?” International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 15 no.2 (2001): 287–308.

_____________________

[1] Reuters. Donald Trump sad to see “beautiful” Confederate statues torn down after Charlottesville violence. ABC News (18 August 2017). Online unter: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-18/donald-trump-sad-to-see-beautiful-statues-torn-down/8818228 (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017).

[2] Fern Shen. Council resolves “to deconstruct” Confederate monuments. Baltimore Brew (15. August 2017). Online unter: https://baltimorebrew.com/2017/08/15/council-resolves-to-deconstruct-confederate-monuments/ (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017).

[3] ABC/AP. “Charlotesville: At least one dead as car ploughs into protesters at white supremacist rally in Virginia.” ABC News (13 August 2017). Online unter: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-13/car-ploughs-into-crowd-at-white-nationalist-rally/8801390 (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017)

[4] Luke Broadwater. “Baltimore City commission recommends removal of two Confederate monuments.” The Baltimore Sun (14. Januar 2016). Online unter: http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/baltimore-city/bs-md-ci-confederate-monuments-20160114-story.html (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017).

[5] ABC/Reuters. “Charlottesville: Baltimore’s Confederate monuments removed overnight after violence.” ABC News (17. August 2017). Online unter: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-17/confederate-monuments-in-baltimore-removed-overnight/8814442 (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017).

[6] Gina Cherelus. “Baltimore removes four Confederate statues after Virginia rally.” Reuters (16 August 2017). Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-virginia-protests-statues-baltimore/baltimore-removes-four-confederate-statues-after-virginia-rally-idUSKCN1AW115 (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[7] Dennis Hengeveld. “The Life and Work of Laura Gardin Fraser.” Coin Update (18 July 2014). Online unter: http://news.coinupdate.com/the-life-and-work-of-laura-gardin-fraser-3389/ (letzter Zugriff 14.09.2017).

[8] Amy Remeikis. “‘An additional plaque’: Bill Shorten’s plan to neutralise Captain Cook debate.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 29. August 2017. Online unter: http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/an-additional-plaque-bill-shortens-plan-to-neutralise-captain-cook-debate-20170828-gy5ioc.html (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017).

[9] Michael Kozlol. “Vandalism of Hyde Park statues is a ‘deeply disturbing’ act of Stalinism,” says Malcolm Turnbull. The Sydney Morning Herald (26 August 2017). Online unter: http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/vandalism-of-hyde-park-statues-is-a-deeply-disturbing-act-of-stalinism-says-malcolm-turnbull-20170826-gy4vmn.html. (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017).

[10] Amy Remeikis (2017), above.

[11] Geoff Barker (2017). Unveiling of Captain Cook’s Statue, Hyde Park, Sydney. Research and Discovery, State Library of New South Wales. Available online: http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/blogs/unveiling-captain-cooks-statue-hyde-park-sydney (last accessed 13 September 2017).

[12] In dem folgenden Artikel werden viele der denkwürdigen mnemonischen Möglichkeiten von Objekten im Museum aufgezeigt: Graham Black. (2011), “Museums, memory and history,” Cultural and Social History: The Journal of the Social History Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 415-427. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/147800411X13026260433275 .

[13] Ahmen Rashid. “After 1,700 years, Buddhas fall to Taliban dynamite.” The Telegraph (12 March 2001). Online unter: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/afghanistan/1326063/After-1700-years-Buddhas-fall-to-Taliban-dynamite.html (letzter Zugriff 14.09.2017).

[14] Max Fischer. “The Truth About Iconic 2003 Saddam Statue-Toppling: ProPublica/New Yorker investigation finds the media got it wrong.” The Atlantic (3. Januar 2011). Online unter: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/01/the-truth-about-iconic-2003-saddam-statue-toppling/342802/ (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017); and Peter Maass. “The Toppling: How the media inflated a minor moment in a long war.” The New Yorker (10 January 2011). Online unter: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/01/10/the-toppling (letzter Zugriff 13.09.2017).

[15] Friederich Nietzsche. (1874/1983). “On the uses and disadvantages of history for life” (trans. by R. J. Hollingdale) Untimely meditations (pp. 57–123). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[16] See, for example, the discussion of the controversial Bells Falls Gorge exhibit on the Australian National Museum’s website: http://www.nma.gov.au/education/resources/multimedia/interactives/bells_falls_gorge_html/why_is_the_display_controversial (letzter Zugriff 14.09.2017).

[17] Katie Pavlich. “A solution to the monument controversy: Build new statues dedicated to minorities in American history.” Townhall (16. August 2017). Online unter: https://townhall.com/tipsheet/katiepavlich/2017/08/16/a-solution-to-the-monument-controversy-build-new-monuments-dedicated-to-minorities-in-american-history-n2369601 (letzter Zugriff 14.09.2017).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© Oxyman. Captain Cook-Denkmal im Hyde Park, Sydney. Aufgenommen nach dem 25. Februar 1879 via flickr.

Übersetzung

Dr. Mark Kyburz (http://www.englishprojects.ch/home)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Parkes, Robert: Sind Denkmäler Geschichte? In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 34, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10215.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 34

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10215

Tags: Australia (Australien), History Politics (Geschichtspolitik), Monument (Denkmal)

Eine deutsche Version finden Sie weiter unten.

The unrealised historical potential of the Lion Monument in Lucerne

Robert Parkes closes his article about the handling of monuments with the question if “appendices” should be added to existing monuments or commemorative plaques “to offer ‘interpretive frames’ for the viewing public, that reflect contemporary critical historical perspectives and are juxtaposed with the original inscriptions […]”.

I would like to respond to this idea by presenting my thoughts about the (in my views unrealised) historical potential of the Lion Monument in Lucerne. Officially opened in 1821, the Lion Monument not only is part of the most popular tourist attractions in Lucerne but also is often visited by locals. While the public has agreed on the admirable artistic work by sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen the political message of the monument has been the subject of vehement discussion.[1]

Carved into a rock, the impressive lion commemorates the Swiss Guards who defended the French royal palace against revolutionists at the storming of the Tuileries.[2] Other than the inscription “In memory of the heroic fight of the Swiss during the storming of the Tuileries on August 10, 1792, their fellow citizens have erected the Lion Monument in 1821”, which has been directly carved into the wall of the park, there is only an information board (that, at least, has been translated into French and English) awaiting the visitor. Nevertheless, the following aspects make a critical and considered appraisal of the monument more difficult:

The information is very short and comprises only a short outline of the building of the monument as well as the meaning of the foreign service (Solddienst) for the Swiss Confederation.

The way this information is conveyed is doubtful: The images used on the plaque are provided without a caption or source; the monument’s Latin inscriptions aren’t translated except for one sentence.

The historical facts, such as the employment of Swiss mercenaries during the French Revolution, aren’t presented from multiple perspectives. The fact that no critical counter perspectives of the French revolutionists or other involved actors are juxtaposed with the message of the monument about the “heroic fight of the Swiss Guards” reveals this. Also, it isn’t mentioned anywhere that parts of the Swiss Guards later went over to the side of the revolutionary troops or had deserted even before the Storming of the Tuileries.[3]

In addition, the controversies that occurred during the planning and construction of the monument aren’t mentioned anywhere. At the time there were many voices raised in opposition to the monument within liberal circles, with many feeling it to be reactionary, royalist and overly luxurious. Others questioned the commemoration of the Swiss soldiers’ foreign services or the necessity of heroes’ monuments in general.[4]

Finally, I would like to point out that the Lion Monument neither conveys the historical facts from multiple perspectives nor in a controversial way. This, again, makes it impossible for visitors to tackle the presented history in a critical and considered way and to form their own opinions about the events that are being commemorated. The same applies to the development of the culture of remembrance or the contextualisation of the monument in the time of its creation, which aren’t mentioned anywhere.

This is even more surprising because a memorial with the fame and the influence of the Lion Monument would be a most appropriate one to provoke discussion and question the public depiction of history. Hence, we can only hope that this unrealised potential will be recognised soon and appropriate measures will be taken, as in Parkes’ own words: It is high time that this monument and the commemorative plaques that go with it will be complemented with “appendices” to create an “interpretive frame” for the public.[5]

References

[1] Claudia Hermann, Ruedi Meier and Josef Brülisauer, Löwen-Denk-Mal: Vom Schicksal der Schweizer Garde zur Touristenattraktion. Begleitheft zur Sonderausstellung im Historischen Museum Luzern 22. September bis 7. November 1993. Luzern: Historisches Museum 1993, 2.

[2] Alain-Jacques Czouz-Tornare, “Tuileriensturm”, Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, http://www.hls-dhs-dss.ch/textes/d/D8916.php (last accessed 17 November 2017).

[3] Philippe Henry, “Schweizergarden”, Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, http://www.hls-dhs-dss.ch/textes/d/D8623.php (last accessed 17 November 2017).

[4] Claudia Hermann, “Das Löwendenkmal in Luzern.” Kunst und Architektur in der Schweiz, no. 1 (2004): 52–55.

[5] Lücke, Martin. “Zum Konzept der Multiperspektivität, Kontroversität und Pluralität.” In Handbuch Praxis des Geschichtsunterrichts 1, edited by Michelle Barricelli, 281-289, Schwalbach/Ts.: Wochenschau Verlag, 2017.

—

Das ungenutzte historische Potential des Löwendenkmals in Luzern

Robert Parkes schliesst seinen Artikel über den Umgang mit Denkmälern mit der Frage, ob bestehende Monumente bzw. Gedenktafeln mit “Anhängen versehen werden [sollen], die der Öffentlichkeit einen ‚interpretativen Rahmen’ bieten, die die zeitgenössische kritische historische Perspektive reflektieren und den Originalinschriften gegenübergestellt werden[…]”.

Daran knüpfe ich mit meinen Gedanken über das (meiner Meinung nach ungenutzte) historische Potential des Löwendenkmals in Luzern an. Das 1821 eingeweihte Löwendenkmal gehört zu den beliebtesten Touristenattraktionen der Stadt Luzern, wird aber auch von Einheimischen rege besucht. Während man sich über die bewundernswerte künstlerische Gesamtleistung des Bildhauers Bertel Thorvaldsen in der Öffentlichkeit einig ist, wird die politische Aussage des Denkmals jedoch heftig diskutiert.[1]

Der imposante, in den Fels gehauene Löwe erinnert an die Schweizergardisten, die am 10. August 1792 den französischen Königspalast beim Tuileriensturm gegen die Anhänger der Revolution verteidigten.[2] Den Besucher erwartet nebst der direkt in die Mauer des Parks eingemeisselten Inschrift “Zum Gedenken an den Heldenkampf der Schweizer beim Tuileriensturm am 10. Aug. 1792 errichteten ihre Mitbürger im Jahre 1821 das Löwendenkmal” lediglich eine Informationstafel (die aber immerhin ins Französische und Englische übersetzt wurde).

Folgende Punkte erschweren jedoch einen kritischen und reflektierten Umgang mit dem Denkmal:

Die Informationen sind sehr knapp und umfassen lediglich einen kurzen Abriss über die Entstehungsgeschichte des Denkmals sowie die Bedeutung der Solddienste für die Schweizer Eidgenossenschaft.

Die Art und Weise, wie diese Informationen vermittelt werden, ist zweifelhaft: Die auf der Tafel verwendeten Bilder verfügen weder über eine Legende noch eine Quellenangabe; der lateinische Text des Denkmals wird abgesehen von einem Satz nicht übersetzt.

Der historische Sachverhalt, nämlich der Einsatz der Schweizer Söldner während der französischen Revolution, wird in keiner Weise multiperspektivisch dargestellt. Dies zeigt sich darin, dass der Aussage des Denkmals über den “heldenhaften Kampf der Schweizergardisten” keinerlei kritische Gegenperspektive der französischen Revolutionäre oder anderer beteiligten Akteure entgegengestellt wird. Auch wird nicht erwähnt, dass ein Teil der Schweizer Gardisten später zu den revolutionären Truppen überliefen beziehungsweise schon vor dem Tuileriensturm desertierten.[3]

Genausowenig werden die Kontroversen thematisiert, zu denen es bei der Planung und Realisierung des Denkmals kam. Aus liberalen Kreisen gab es nämlich bereits zu dieser Zeit Stimmen, die das Denkmal als reaktionär, royalistisch oder zu prunkvoll empfanden. Andere stellten die Tatsache, dass der Fremdendienste der Schweizer Soldaten gedacht werde bzw. die Notwendigkeit von Heldendenkmälern grundsätzlich in Frage.[4]

Abschliessend lässt sich also festhalten, dass der historische Sachverhalt anhand des Löwendenkmals weder multiperspektivisch noch kontrovers vermittelt wird. Dies verunmöglicht wiederum, dass sich Besucher kritisch und reflektiert mit der dargestellten Geschichte auseinandersetzen und sich ihr eigenes Urteil über die Geschehnisse bilden können. Dasselbe gilt für die Entwicklung der Erinnerungskultur bzw. die Einbettung des Denkmals in die Zeit seiner Entstehung, welche nirgends thematisiert werden.[5] Dies ist umso erstaunlicher, da sich ein Ort mit der Bekanntheit und Ausstrahlung eines Löwendenkmals bestens eignen würde, um den öffentlichen Umgang mit Geschichte zu diskutieren und zu hinterfragen. Es bleibt also zu hoffen, dass dieses ungenutzte Potential bald erkannt wird und geeignete Massnahmen ergriffen werden. Oder in Parkes Worten: Es ist höchste Zeit, dass dieses Denkmal und die dazugehörigen Gedenktafeln mit “Anhängen” ergänzt werden, um einen “interpretativen Rahmen” für die Öffentlichkeit zu schaffen.

Anmerkungen

[1] Claudia Hermann, Ruedi Meier and Josef Brülisauer, Löwen-Denk-Mal: Vom Schicksal der Schweizer Garde zur Touristenattraktion. Begleitheft zur Sonderausstellung im Historischen Museum Luzern 22. September bis 7. November 1993. Luzern: Historisches Museum 1993, 2.

[2] Alain-Jacques Czouz-Tornare, “Tuileriensturm”, Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, http://www.hls-dhs-dss.ch/textes/d/D8916.php (letzter Zugriff 17.11.2017).

[3] Philippe Henry, “Schweizergarden”, Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, http://www.hls-dhs-dss.ch/textes/d/D8623.php (letzter Zugriff 17.11.2017).

[4] Claudia Hermann, “Das Löwendenkmal in Luzern.” Kunst und Architektur in der Schweiz, no. 1 (2004): 52–55.

[5] Lücke, Martin. “Zum Konzept der Multiperspektivität, Kontroversität und Pluralität.” In Handbuch Praxis des Geschichtsunterrichts 1, edited by Michelle Barricelli, 281-289, Schwalbach/Ts.: Wochenschau Verlag, 2017.