Abstract: In Europe, contemporary political debates are heavily influenced by history and memory issues. European citizens have multi-layered identities, which reflect the active role played by the past in the present. The Europe Union (EU) consists of local identities and the construction of collective regional, national, and pan-European “heimats” and “realms of memory”. The process of Europeanization in a union comprising Eastern European and Balkan countries (2004, 2007, and 2013) seeks to reshape memories based on a supra-national history. The EU, cultural heritage institutions, and public historians should all contribute to questioning history and memory issues within a transnational EU public sphere.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10113.

Languages: FrançaisEnglish, Deutsch

En Europe, les débats politiques contemporains sont fortement influencés par l’histoire et la mémoire. Les citoyens européens possèdent des identités diverses qui reflètent le rôle actif du passé dans le présent. L’Union européenne (UE) est faite d’identités locales et de la construction d’«heimat» collectifs régionaux, nationaux et pan-européens et de «lieux de mémoire». Le processus d’intégration européenne dans une Union comprenant les pays d’Europe orientale et des Balkans (2004, 2007 et 2013) demande de remodeler des mémoires sur la base d’une histoire supranationale. L’Union européenne directement, les institutions liées au patrimoine culturel et les historiens publics devraient ainsi aider à interroger l’histoire et les mémoires actives dans la sphère publique transnationale de l’UE.[1]

Histoire publique contre division européenne?

“L’Union européenne (UE) a été créée dans le but de mettre fin aux guerres qui ont régulièrement ensanglanté le continent, et qui ont culminé dans la Seconde guerre mondiale“.[2] Dans ce contexte, aujourd’hui, l’euro-scepticisme se répand dans toute l’Europe: les souvenirs nationaux sont divergents et encore une fois contradictoires. L’histoire de l’Europe d’après-guerre est perçue comme fragmentée, compétitive et souvent divergente. L’UE, le projet politique et institutionnel le plus important du XXe siècle, est confrontée à une crise globale.[3] Les citoyens de l’UE sont cependant les protagonistes directs d’une telle crise: des États membres fondateurs comme la France et la Hollande ont voté contre la Constitution de l’UE (2005). De plus, certains pays d’Europe de l’Est, malgré la possibilité de construire un «récit national» qui aurait inclus l’Europe de l’Est et l’Europe occidentale,[4] réinterprètent le passé en termes nationalistes, anti-européens, patriotiques, xénophobes, isolationnistes et antilibéraux. Les murs sont construits d’abord et avant tout dans les consciences individuelles, rejetant les valeurs de la citoyenneté dérivée de la Révolution française au nom d’une «pureté» inventée des cultures traditionnelles contre la «contamination» du globalisme.

Memoryland, l’Europe, Terre de Mémoires

“Les historiens sont divisés dans leurs visions du passé européen: devraient-ils encore promouvoir la contribution idéale de l’intégration européenne au maintien de la paix, comme le fait la Commission européenne? Ou devraient-ils rester en dehors de la dimension politique”[5]

suggère Wolfgang Schmale? Bien sûr, les historiens publics ont aujourd’hui la tâche difficile de promouvoir les valeurs essentielles d’une coexistence pacifique entre les peuples du continent, comme la démocratie, la tolérance et les droits de l’homme et de contribuer à la construction d’une mémoire collective transnationale basée sur le patrimoine historique de l’Europe. Un historien public doit savoir qu’il joue un rôle social en produisant – souvent par le biais des médias numériques – une histoire «utile» pour l’Europe aujourd’hui.[6] En effet, les historiens publics ne devraient pas seulement réagir contre la construction des légendes nationales. Au contraire, ils devraient devenir proactifs, choisir de favoriser des valeurs positives qui sont renforcées par une lecture attentive de l’histoire européenne après la Première Guerre mondiale. Dans «memoryland» (le pays de la mémoire), un continent dans lequel le passé influence profondément le présent, les historiens publics peuvent contribuer à développer une identité européenne commune qui éduque les communautés au passé.[7] Pierre Nora écrit que «la fonction de l’historien … est d’interroger cette transformation, d’en élucider les ressorts historiques et, si l’on ose le dire, de refabriquer pour les hommes d’aujourd’hui une mémoire habitable et à la mesure de l’avenir qu’ils ont à dessiner».[8]

Dans ce contexte, la public history favorise activement l’histoire d’un espace constitutionnel européen inclusif basé sur une identité commune[9] comme la Maison de l’histoire européenne, ouverte à Bruxelles en mai 2017, est en train de proposer.[10] La meilleure connaissance de l’histoire européenne fournie par le MHE peut aider à rapprocher les citoyens européens du processus d’intégration de l’UE.[11] L’activisme dans le présent contribue également à créer ce que Luisa Passerini appelle une «nouvelle utopie» qui rend possible la relation entre les Européens et les nombreux «autres», à l’intérieur et à l’extérieur de l’Union.[12]

14-18 c’est notre histoire

La célébration du Centenaire de la Première Guerre mondiale a jusqu’à présent favorisé une meilleure connaissance et sensibilisation à l’égard des passés difficiles du continent et à l’identité commune européenne. Réfléchir sur la Première Guerre mondiale et sur les passés conflictuels des nations avant 1914, favorise aujourd’hui, la compréhension de ce qu’est une Europe unie après la Seconde Guerre mondiale.[13]

La célébration du rôle de maintien de la paix de l’UE et de l’histoire de l’intégration européenne a eu lieu lors d’une exposition majeure à Bruxelles: 14-18 est notre histoire.[14] L’exposition a également présenté un «message utile» pour aujourd’hui.[15] On demandait aux visiteurs de répondre à des questions telles que: qu’auriez-vous fait à la veille de la Première Guerre? La mémoire de la Première Guerre mondiale nous concerne tous à la lumière du contexte politique international d’aujourd’hui. Le parcours de l’exposition se terminait ainsi dans une pièce sombre avec projections de films et photographies. Une image spécifique clôturait le parcours historique à travers le violent vingtième siècle: elle représentait les dirigeants de l’UE avec le prix Nobel pour la paix de 2012 et le drapeau européen. Pour un historien public, il n’y a rien de peu professionnel ni d’instrumental à suggérer aux visiteurs que le siècle court, à partir du cataclysme de la Première Guerre mondiale, des totalitarismes qui en sont issus, et de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, débouche sur la réception d’un tel prix. La narration montrait clairement à tous les visiteurs, qu’une Europe de paix était née de la mémoire du champ de bataille de Verdun et jusqu’au traité de Lisbonne (2009). Cette exposition intégrait ainsi le passé comme dimension vivante du présent.

Les historiens publics poursuivent des objectifs publics importants

L’histoire a traditionnellement été maltraitée dans une rhétorique étatique, en politique et abusée par les gouvernements dans les musées, les expositions et même dans les livres scolaires. Les interprétations du passé ont été utilisées pour justifier les guerres et les génocides, le racisme, les positions anti-mondialiste et une histoire nationale héroïque qui rejette les ombres du passé et favorise la rhétorique patriotique des «romans nationaux». Au lieu de cela, les historiens publics transmettent des passés plus complexes et plus scientifiques au public. Ils doivent être directement impliqués dans les politiques de la mémoire et dans la valorisation du patrimoine culturel commun. Ils doivent rechercher à atteindre des objectifs publics et se donner un “but public” en promouvant la valeur civique de la profession d’historien.[16]

Pour conclure, on peut affirmer qu’un des objectifs de l’histoire publique est de mener des recherches originales avec et pour les citoyens européens et, dans la mesure du possible, de construire une mémoire active commune à propos de l’intégration européenne. L’histoire publique doit être critique, participative et capable de synthèse pour aujourd’hui et devrait faire de l’histoire européenne une partie intégrante de notre identité.

____________________

Littérature

- Bottici, Chiara, and Benoît Challand. Imagining Europe, Myth, Memory and Identity. Cambridge: University Press, 2013.

- Kaiser, Wolfram, Stefan Krankenhagen, and Kerstin Poehls. Exhibiting Europe in museums: transnational networks, collections, narratives and representations. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014.

- Macdonald, Sharon. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. London: Routledge, 2013.

Liens externe

- Inventing Europe, European Digital Museum for Science and Technology, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/ (last accessed 12 September 2017).

- House of European History, https://historia-europa.ep.eu/ (dernier accès 12.09.2017).

- CVCE.eu by Uni.lu, https://www.cvce.eu/ (dernier accès 12.09.2017).

____________________

[1] Les objectifs du Programme sont le «soutien aux initiatives en faveur de la mémoire européenne et de la participation civique à échelle européenne»: «Contribuer à faire comprendre l’UE, son histoire et sa diversité; promouvoir la citoyenneté européenne et améliorer les conditions de la participation civique et démocratique au niveau de l’UE; sensibiliser au travail de mémoire, à l’histoire et aux valeurs communes; encourager la participation démocratique des citoyens européens». Promu par la Commission Européenne et organisé par le Règlement (UE) n° 390/2014 du Conseil du 14 avril 2014 établissant le programme «L’Europe pour les citoyens» pour la période 2014-2020» (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?qid=1398334046443&uri=OJ%3AJOL_2014_115_R_0002). Agence EACA (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency): Europe pour les citoyens, URL: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/europe-pour-les-citoyens_fr

[2] “L’histoire de l’Union européenne” in Europa.eu, https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/history_fr

[3] Cela a été le cas grâce à l’important projet d’histoire publique numérique coordonné par l’historien néerlandais Johan Schot, Inventing Europe, European Digital Museum for Science and Technology, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/ et avec la publication d’une série de livres sur le Making of Europe (http://www.makingeurope.eu/) coordonnés par Johan Schot and Phil Scranton, Making Europe: Technology and Transformations, 1850-2000, Basingstoke: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2013-2018, http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14816.

[4] “Dans un nouveau Focal Point, Eurozine cherche à élargir la question au-delà de la fracture historique Est-Ouest. Comment les interprétations contestées des événements historiques récents qui unissent et divisent les sociétés européennes sont-elles actives dans le présent?”, en anglais dans “Multilingual cultural e-zine that links up and promotes over 100 cultural journals from all over Europe” in Eurozine, 28 Février 2011, http://www.eurozine.com/european-histories-concord-and-conflict/

[5] “…L’Union européenne, elle-même le produit d’un certain nombre d’institutions et de traités précédents, représente la meilleure expression d’une nouvelle qualité de l’européanisation depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale ….” Wolfgang Schmale: “Processes of Europeanization”, dans European History Online (EGO), published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 03-12-2010. URL: http://www.ieg-ego.eu/schmalew-2010b-en URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-20101025144 [28-08-2017].

[6] Serge Noiret: “Public history as “useful history” before voting for Europe, May 22-25, 2014”, dans Digital & Public History, Avril 2014, http://dph.hypotheses.org/380 et “La Public History, una medicina necessaria nell’Union Europa oggi”, dans Fondazione Feltrinelli; La nostra città futura, 1er Aout 2017, http://fondazionefeltrinelli.it/la-public-history-medicina-necessaria-nell-unione-europea-oggi/.

[7] Sharon Macdonald: Memorylands: heritage and identity in Europe today, London, Routledge, 2013. “Memorylands […] fournit de nouvelles idées sur la façon dont on utilise et on reconstitue la mémoire et le passé en Europe. […]”.La construction d’une identité européenne a également été étudiée par une philosophe du politique, Chiara Bottici: “European Identity and the Politics of Remembrance” dans Karin Tilmans, Frank van Vree, Jay Winter (coord.): Performing the past: memory, history, and identity in modern Europe., Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010, pp.335-359; Chiara Bottici et Benoît Challand: Imagining Europe, Myth, Memory and Identity, Cambridge University Press, 2013. Les musées d’histoire jouent un rôle dans la construction d’une identité européenne commune à travers une «muséification» de l’histoire de l’intégration européenne. Voir de Wolfram Kaiser, Stefan Krankenhagen and Kerstin Poehls: Exhibiting Europe in museums: transnational networks, collections, narratives and representations, New York: Berghahn Books, 2014. Cf. Aline Sierp: History, Memory and Trans-European Identity: Unifying Divisions. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[8] «…La fonction de l’historien … est d’interroger cette transformation, d’en élucider les ressorts historiques et, si l’on ose le dire, de refabriquer pour les hommes d’aujourd’hui une mémoire habitable et à la mesure de l’avenir qu’ils ont à dessiner.», Pierre Nora: Historien Public., Paris: Gallimard, 2011, pp.446-447.

[9] Markus J. Prutsch, Recherche pour la commission CULT – L’identité européenne, Parlement européen, département thématique des politiques structurelles et de cohésion, Bruxelles, 2017, Brussels, IP/B/CULT/NT/2017-004, PE 585.921, Avril 2017, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/585921/IPOL_STU(2017)585921_FR.pdf. Cette recherche suit une autre étude rédigée par le même auteur sur demande du Parlement Européen, Direction Générale des Politiques Internes Département Thématique B: Politiques Structurelles et de Cohésion, Culture et Éducation La Mémoire Historique Européenne: Politiques, Défis et Perspectives, NOTE , IP/B/CULT/NT/2013-002 Septembre 2013 http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2013/513977/IPOL-CULT_NT(2013)513977_FR.pdf

[10] Maison de l’histoire européenne https://historia-europa.ep.eu/fr. European Parliament, House of European History: Guidebook to the Permanent Exhibition, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017, DOI 10.2861/348428.

[11] «Pour être mobilisateur, [le projet européen aujourd’hui] doit être soutenu par les citoyens européens. Seul son caractère populaire permettrait de confirmer et de souder la construction européenne.» Frédéric Clavert: Narrating Europe : un exercice de réflexivité in Devenir historien-ne Méthodologie de la recherche et historiographie en master Histoire, URL: [http://devhist.hypotheses.org/2207].

[12] “L’utopie est examinée … comme expression d’une notion d’Europe et d’être européen qui critique toutes les formes d’eurocentrisme et reconnaît la contribution de l’autre (en termes, par exemple, de race et de genre) dans la formation du sujet.” (Luisa Passerini. Memory and utopia: the primacy of intersubjectivity., London: Equinox, 2007, p.8.)

[13] “La Première Guerre mondiale est un point de référence important pour la création d’une conscience historique transnationale et mondiale, offrant une chance unique de discuter des racines et des possibilités d’intégration européenne”, dans “The First World War and European historical consciousness”, in World War One Goes World Wide Web, 8 October 2014 Brussels”, http://www.1914-1918-online.net/res/A4_14-18_EU-Broschuere_CMYK_vd.pdf.

[14] Musée royal de l’Armée et d’Histoire Militaire: 14-18, C’est notre Histoire. Bruxelles, 26 Février 2014 – 26 Avril, 2015., http://www.expo14-18.be/ la dernière version du site web a été archivée dans l’Internet Archive le 24 Février 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160224063758/http://www.expo14-18.be/.

[15] 14-18 c’est notre histoire, https://tempora-expo.be/14-18-cest-notre-histoire/. L’exposition a eu lieu à Bruxelles de février 2014 à novembre 2015 et a attiré plus de 175 000 visiteurs.

[16] Le rôle actif d’un tel historien public est théorisé par un historien britannique Alix Green, dans un récent livre sur History, Politics and Public Purpose. Pour Green, un historien public n’est pas un simple consultant quand l’histoire compte au présent. Green écrit que «les historiens publics doivent «donner une impulsion morale, méthodologique et intellectuelle au travail de manière à contribuer à la vie publique et au bien-être social». Alix R. Green: History, policy and public purpose: historians and historical thinking in government, London : Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

____________________

Crédits illustration

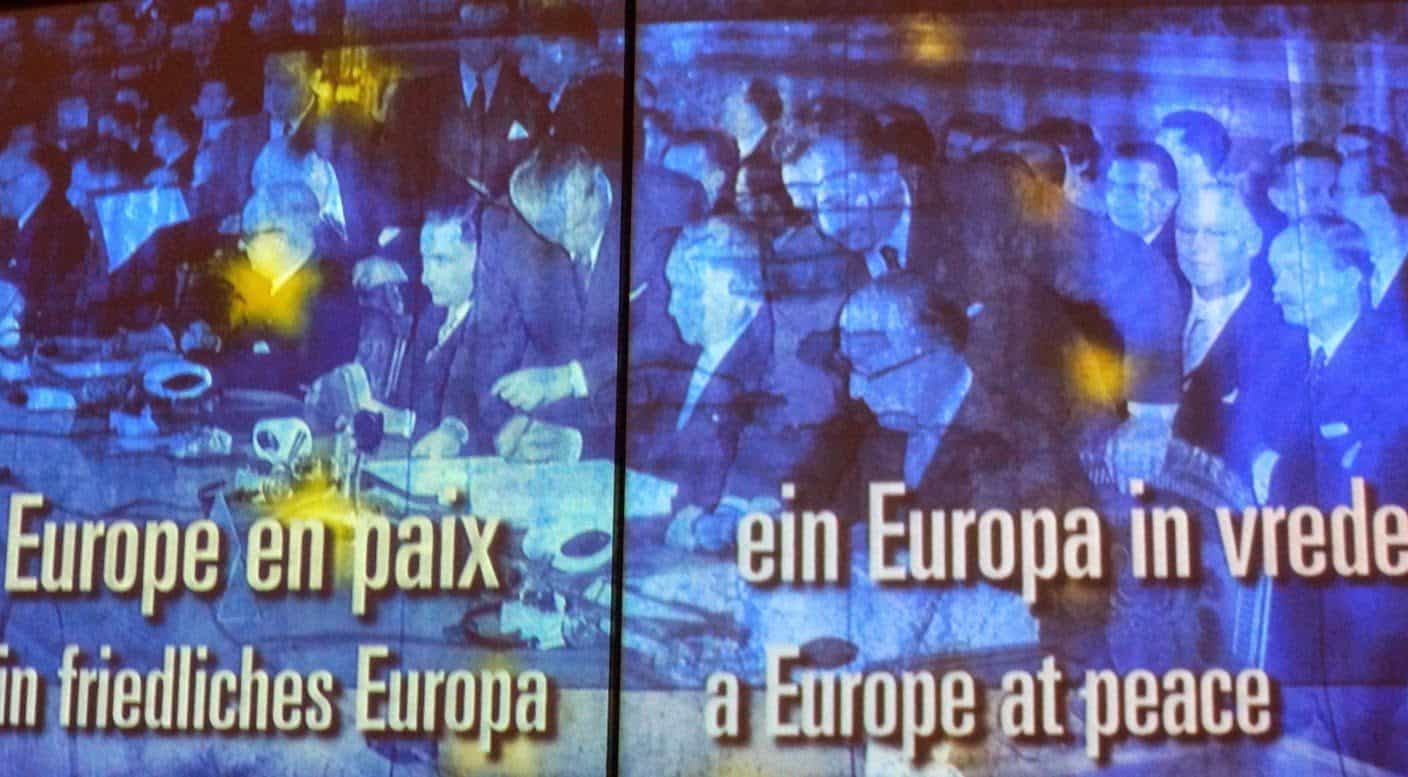

© Serge Noiret. Collage: Une Europe en paix.

Citation recommandée

Noiret, Serge: L’Histoire Publique, une cure nécessaire pour l’Union européenne aujourd’hui ?. Dans: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 32, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10113.

In Europe, contemporary political debates are heavily influenced by history and memory issues. European citizens have multi-layered identities, which reflect the active role played by the past in the present. The Europe Union (EU) consists of local identities and the construction of collective regional, national, and pan-European “heimats” and “realms of memory”. The process of Europeanization in a union comprising Eastern European and Balkan countries (2004, 2007, and 2013) seeks to reshape memories based on a supra-national history. The EU, cultural heritage institutions, and public historians should all contribute to questioning history and memory issues within a transnational EU public sphere.[1]

Public history versus European division?

“The EU is set up with the aim of ending the frequent and bloody wars between neighbors, which culminated in the Second World War.”[2] Against this backdrop, Euro-skepticism is spreading across Europe: national memories are divergent and once again conflicting. The history of postwar Europe is perceived as fragmented, competitive, and often contradictory. The EU, the most important political and institutional project of the 20th century, is facing a global crisis.[3] EU citizens, however, are the direct protagonists of such a crisis: founding members such as France and Holland voted against the EU Constitution (2005). Moreover, some Eastern European countries, despite the possibility of building a “grand narrative,” which would have included both Eastern and Western Europe,[4] reinterpret the past in nationalistic, anti-European, patriotic, xenophobic, isolationist, and illiberal terms. Walls are built first and foremost in individual consciousnesses, rejecting the values of citizenship derived from the French Revolution in the name of an invented “purity” of traditional cultures against the “contamination” of globalism.

Memoryland

Wolfgang Schmale has observed:

“Historians are divided in their visions of the European past: should they still promote the idealistic contribution of the peace-keeping effect of European integration, as the EU Commission does? Or should they remain outside the policy dimension?”[5]

Public historians today definitely face the difficult task of promoting the essential values of peaceful coexistence in Europe, such as democracy, tolerance, and human rights. They are also called upon to contribute to build a transnational collective memory based on Europe’s historical heritage. A public historian must be aware that he or she is fulfilling a social role when producing—often through digital media—a “useful” history for today’s Europe. Indeed, the work of public historians should not only be reactive, that is, aiming to defeat the construction of national legends. On the contrary, they should become proactive, choosing to favor positive values that are reinforced by a careful reading of European history after WW1.[6] In “Memoryland,” a continent in which the past deeply influences the present, public historians can contribute to developing a common European identity and educating communities about the past.[7] Pierre Nora writes that “the effect of the work of historians on […] memory is […] to refashion for today’s men a livable memory and one up to the future they have to build.”[8]

In this context, public history actively promotes the history of an inclusive European constitutional space based on a common identity.[9] This role is now assumed by the House of European History (HEH), opened in Brussels in May 2017.[10] The better knowledge of European history provided by the HEH can help bring European citizens back to the EU integration process.[11] Activism in the present also helps create what Luisa Passerini calls a “new utopia,” which enables the relationship between Europeans and the many “others”, inside and outside the Union.[12]

14-18 is our history

The celebration of the WW1 Centenary has so far promoted a better knowledge and awareness of Europe’s difficult pasts and its common identity. Reflecting on WW1, and on the conflicting national pasts before 1914, fosters today’s understanding of what a united Europe meant after WW2.[13]

The EU’s peacekeeping role and the history of its integration were celebrated at a major exhibition in Brussels: 14-18 is our history.[14] The exhibition also conveyed a “useful message” for today:[15] visitors were asked to answer various questions, including what they would have done on the eve of the First War? The memory of WW1 concerns us all in the light of today’s international political context. The exhibition ended in a dark room featuring movies and photographs. One specific picture concluded the historical journey through the violent twentieth century and depicted the then-EU leaders with the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize and the European flag. There is nothing non-professional or instrumental about the curators, as public historians, showing that eventually the short century, beginning with the cataclysm of WW1, the resulting totalitarianism, and the devastation caused by WW2, climaxed in the award. It was clear to all visitors that a Europe of Peace was born from the memory of Verdun up to the Treaty of Lisbon (2009). This exhibition integrated the past as a living dimension of the present.

Public historians achieving relevant public goals

History has traditionally been abused in state rhetoric, in politics, and by governments in museums, exhibitions, and even in schoolbooks. Interpretations of the past have been used to justify wars and genocides, racism, anti-globalization stances, and a heroic national history that rejects the shadows of the past and promotes a patriotic rhetoric. Instead, public historians communicate more complex and “scientifically safe” pasts to the public. They must be directly involved in memory policies and in enhancing a common cultural heritage. They must achieve public goals and have a “public purpose” by promoting the civic value of the history profession.[16]

To conclude, one objective of public history is to pursue original research with and for European citizens; another is to build a common active memory about European integration. Public history has to be critical, participatory, and capable of synthesis for our current predicament and should invest in making European history an integral part of our own identity.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bottici, Chiara, and Benoît Challand. Imagining Europe, Myth, Memory and Identity. Cambridge: University Press, 2013.

- Kaiser, Wolfram, Stefan Krankenhagen, and Kerstin Poehls. Exhibiting Europe in museums: transnational networks, collections, narratives and representations. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014.

- Macdonald, Sharon. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. London: Routledge, 2013.

Web Resources

- Inventing Europe, European Digital Museum for Science and Technology, http://www.inventingeurope.eu/ (last accessed 12 September 2017).

- House of European History, https://historia-europa.ep.eu/ (last accessed 12 September 2017).

- CVCE.eu by Uni.lu, https://www.cvce.eu/ (last accessed 12 September 2017).

_____________________

[1] See the funding initiatives aimed at strengthening remembrance and enhancing civic participation at EU institutional level. Promoted by the EU Commission and organized by the Council Regulation (EU) No 390/2014 of 14 April 2014 (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2014_115_R_0002&qid=1398334046443) the ‘Europe for Citizens’ programme has been established for the period 2014-2020. “The aim of this programme is to contribute to citizens’ understanding of the EU, its history and diversity; to foster European citizenship and to improve conditions for civic and democratic participation at EU level; to raise awareness of remembrance, common history and values; to encourage democratic participation of citizens at EU level….,” EACA Agency (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency): Europe for Citizens, URL: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/europe-for-citizens_en .

[2] “The history of the European Union,” in Europa.eu, https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/history_en

[3] See, for instance, Inventing Europe, European Digital Museum for Science and Technology, the important digital public history project coordinated by the Dutch historian Johan Schot; see also the publication of Making Europe: Technology and Transformations, 1850-2000 (http://www.makingeurope.eu/), a series of books edited by Johan Schot and Phil Scranton, Basingstoke: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2013-2018, http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14816.

[4] “In a new Focal Point, Eurozine seeks to broaden the question beyond the East-West historical divide. How are contested interpretations of historical and recent events made active in the present, both uniting and dividing European societies?”; see “Multilingual cultural e-zine that links up and promotes over 100 cultural journals from all over Europe,” Eurozine, 28 February 2011, http://www.eurozine.com/european-histories-concord-and-conflict/

[5] “…The European Union, itself the product of a number of predecessor institutions and treaties, represents the most sustained expression of a new quality of Europeanization since the Second World War….”; see Wolfgang Schmale, “Processes of Europeanization,”European History Online (EGO), published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2010-12-03, URL: http://www.ieg-ego.eu/schmalew-2010b-en URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-20101025144 [2017-08-28].

[6] Serge Noiret, “Public history as “useful history” before voting for Europe, May 22-25, 2014,”Digital & Public History, April 2014, http://dph.hypotheses.org/380 e “La Public History, una medicina necessaria nell’Union Europa oggi,” in Fondazione Feltrinelli; La nostra città futura, Agosto 1, 2017, http://fondazionefeltrinelli.it/la-public-history-medicina-necessaria-nell-unione-europea-oggi/.

[7] Sharon Macdonald: Memorylands: heritage and identity in Europe today (London, Routledge, 2013). “Memorylands […] provides new insights into how memory and the past are being performed and reconfigured in Europe […].” The construction of a European identity has been also studied by political philosopher Chiara Bottici: “European Identity and the Politics of Remembrance,” in Karin Tilmans, Frank van Vree, and Jay Winter (eds.): Performing the past: memory, history, and identity in modern Europe (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010, pp. 335–359); Chiara Bottici and Benoît Challand: Imagining Europe, Myth, Memory and Identity (Cambridge University Press, 2013). Further, history museums are playing a role in building a common European identity through the “museification” of European Integration History. For a discussion, see Wolfram Kaiser, Stefan Krankenhagen and Kerstin Poehls: Exhibiting Europe in museums: transnational networks, collections, narratives and representations (New York: Berghahn Books, 2014). Cf. Aline Sierp: History, Memory and Trans-European Identity: Unifying Divisions. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[8] Pierre Nora, Historien Public (Paris: Gallimard, 2011, pp. 446–447).

[9] Markus J. Prutsch, Research for CULT Committee – European Identity, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, IP/B/CULT/NT/2017-004, PE 585.921, April 2017, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/585921/IPOL_STU(2017)585921_EN.pdf. This policy paper follows another study written by the same author for the European Parliament, Directorate-general for Internal Policies Policy Department, b: Structural and Cohesion Policies Culture and Education, Culture and Education: European Historical Memory: Policies, Challenges and Perspectives, 2013, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2013/513977/IPOL-CULT_NT(2013)513977_EN.pdf

[10] House of European History https://historia-europa.ep.eu/. European Parliament, House of European History: Guidebook to the Permanent Exhibition, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017, DOI 10.2861/348428.

[11] “Pour être mobilisateur, [le projet européen aujourd’hui] doit être soutenu par les citoyens européens. Seul son caractère populaire permettrait de confirmer et de souder la construction européenne.” See Frédéric Clavert: Narrating Europe : un exercice de réflexivité in Devenir historien-ne Méthodologie de la recherche et historiographie en master Histoire, URL: [http://devhist.hypotheses.org/2207].

[12] “Utopia is examined … as an expression of a concept of Europe and of being European which is critical of all forms of Eurocentrism and acknowledges the contribution of the other (in terms, for example, of race and gender) in the formation of the subject.” (Luisa Passerini. Memory and utopia: the primacy of intersubjectivity, London: Equinox, 2007, p. 8.)

[13] “The First World War is an important point of reference for the creation of a transnational and global historical consciousness, offering a unique chance to discuss the roots of and possibilities for European integration” in “The First World War and European historical consciousness,” in World War One Goes World Wide Web, 8 October 2014 Brussels,” http://www.1914-1918-online.net/res/A4_14-18_EU-Broschuere_CMYK_vd.pdf.

[14] Musée royal de l’Armée et d’Histoire Militaire: 14-18, It’s our History. Brussels, February 26, 2014 – April, 26, 2015., http://www.expo14-18.be/ the last available version of this website has been saved in the Internet Archive on February 24, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160224063758/http://www.expo14-18.be/.

[15] 14-18 c’est notre histoire, https://tempora-expo.be/14-18-cest-notre-histoire/. The exhibition took place in Brussels from February 2014 – November 2015 and attracted more than 175.000 visitors.

[16] Such an active role for the public historian is theorized by the British historian Alix Green in a recent book on History, Politics and Public Purpose. For Green, a public historian is not a mere consultant when history matters for the present. Green writes that public historians must “give moral, methodological and intellectual impetus to work in ways that contribute to public life and social welfare.” Alix R. Green: History, policy and public purpose: historians and historical thinking in government (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

_____________________

Image Credits

© Serge Noiret. Collage: A Europe at peace.

Recommended Citation

Noiret, Serge: Public History, A Necessity in Today’s European Union? In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 32, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10113

Zeitgenössische politische Debatten werden in Europa stark von Geschichte und Erinnerungsfragen beeinflusst. Europäischen BürgerInnen haben vielschichtige Identitäten, die die aktive Rolle der Vergangenheit in der Gegenwart widerspiegeln. Die Europäische Union (EU) besteht aus lokalen Identitäten und dem Aufbau kollektiver regionaler, nationaler und pan-europäischer “Heimaten” und “Erinnerungswelten”: Der Prozess der Europäisierung in einer Union bestehend aus osteuropäischen und balkanischen Ländern (2004, 2007 und 2013) zielt darauf ab, Erinnerungen auf der Grundlage einer supranationalen Geschichte neu zu gestalten. Die EU, Kulturerbe-Institutionen und Public Historians sollten alle dazu beitragen, Geschichts- und Gedächtnisfragen im Rahmen einer transnationalen Öffentlichkeit der EU zu hinterfragen.[1]

Public History contra europäische Spaltung?

“Die EU wurde mit dem Ziel gegründet, die häufigen und blutigen Kriege zwischen Nachbarn, die im Zweiten Weltkrieg ihren Höhepunkt fanden, zu beenden.”[2] Vor diesem Hintergrund verbreitet sich die Euro-Skepsis in ganz Europa: Nationale Erinnerungen divergieren und stehen wieder einmal im Widerspruch. Die Nachkriegsgeschichte Europas wird als zersplittert, als wettstreitend und oft als widersprüchlich wahrgenommen. Die EU, das wichtigste politische und institutionelle Projekt des 20. Jahrhunderts, befindet sich in einer globalen Krise.[3] Die EU-BürgerInnen sind jedoch die direkten ProtagonistInnen einer solchen Krise: Gründungsmitglieder wie Frankreich und Holland haben gegen die EU-Verfassung (2005) gestimmt. Darüber hinaus interpretieren einige osteuropäische Länder, trotz der Möglichkeit, eine “große Narration” zu erstellen, die sowohl Ost- als auch Westeuropa hätte einschließen können,[4] die Vergangenheit neu als nationalistisch, antieuropäisch, patriotisch, fremdenfeindlich, isolationistisch und unliberal. Die Mauern werden in erster Linie im individuellem Bewusstsein errichtet, indem jene staatsbürgerlichen Werte abgelehnt werden, die aus der Französischen Revolution im Namen einer erfundenen “Reinheit” der traditionellen Kulturen gegen die “Kontamination” des Globalismus abgeleitet wurden.

Erinnerungsland

Wolfgang Schmale meint dazu:

“Historiker sind gespalten in ihren Visionen von der europäischen Vergangenheit: Sollen sie noch den idealistischen Beitrag der friedenserhaltenden Wirkung der europäischen Integration fördern, wie es die EU-Kommission tut? Oder sollten sie sich außerhalb der politischen Dimension aufhalten?”[5]

Heute stehen Public Historians vor der schwierigen Aufgabe, die wesentlichen Werte des friedlichen Zusammenlebens in Europa wie Demokratie, Toleranz und Menschenrechte zu fördern. Sie sind auch aufgerufen, einen Beitrag zum Aufbau eines transnationalen kollektiven Gedächtnisses auf der Grundlage des historischen Erbes Europas zu leisten. HistorikerInnen müssen sich bewusst sein, dass sie bei der Herstellung — oft durch digitale Medien — einer “nützlichen” Geschichte für das Europa von heute eine soziale Rolle wahrnehmen. In der Tat sollte die Arbeit von Public Historians nicht bloss reaktiv sein, d. h. die Konstruktion von nationalen Legenden überwinden. Im Gegenteil, sie sollten aktiv werden und positive Werte bevorzugen, die durch eine sorgfältige Lektüre der europäischen Geschichte nach dem ersten Weltkrieg verstärkt werden. In “Memoryland”, einem Kontinent, auf dem die Vergangenheit die Gegenwart stark beeinflusst, können Public Historians dazu beitragen, eine gemeinsame europäische Identität zu entwickeln und Gemeinschaften über die Vergangenheit aufzuklären.[7] Diesbezüglich meint Pierre Nora , dass “die Wirkung der Geschichtsforschung auf […] das Gedächtnis […] darin besteht, für die Menschen von heute eine lebenswerte Erinnerung zu gestalten, die auch bis in die Zukunft reicht, die es zu bauen gilt.”[8]

In diesem Zusammenhang befördert Public History aktiv die Geschichte eines integrativen europäischen Verfassungsraums auf der Grundlage einer gemeinsamen Identität.[9] Diese Rolle übernimmt nun das im Mai 2017 in Brüssel eröffnete Haus der europäischen Geschichte. Die bessere Kenntnis der europäischen Geschichte, die dadurch geschaffen wird, kann dazu beitragen, die europäischen BürgerInnen wieder in den EU-Integrationsprozess einzubinden.[11] Aktivismus in der Gegenwart trägt auch dazu bei, was Luisa Passerini eine “neue Utopie” nennt, die das Verhältnis zwischen EuropäerInnen und den vielen “Anderen” innerhalb und außerhalb der Union ermöglicht.[12]

14-18 ist unsere Geschichte

Die Hundertjahrfeier des Ersten Weltkriegs hat bisher zu einer besseren Kenntnis und einem besseren Bewusstsein der schwierigen Vergangenheit und der gemeinsamen Identität Europas beigetragen. Die Reflexion über den Ersten Weltkrieg und die widersprüchliche nationale Vergangenheit vor 1914 fördert das heutige Verständnis dessen, was ein vereintes Europa nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg bedeutete.[13]

Die friedenserhaltende Rolle der EU und ihre Intergrationsgeschichte wurden anlässlich einer großen Ausstellung in Brüssel gefeiert: “14-18, es ist unsere Geschichte.”[14] Die Ausstellung vermittelte auch eine “nützliche Botschaft” für heute:[15] Die BesucherInnen wurden gebeten, verschiedene Fragen zu beantworten, z.B. was sie am Vorabend des Ersten Krieges getan hätten? Die Erinnerung an den Ersten Weltkrieg betrifft uns alle im Kontext des heutigen internationalen politischen Kontexts. Die Ausstellung endete in einem dunklen Raum, in dem verschiedene Filme und Fotografien projiziert wurden. Die historische Reise durch das gewalttätige 20. Jahrhundert endete mit einem ganz spezifischen Bild, auf dem die damaligen EU-FührerInnen mit dem Friedensnobelpreis 2012 und der europäischen Flagge zu sehen waren. Es ist weder unprofessionell noch instrumentalisierend, wenn die AusstellungskuratorInnen, als Public Historians fungierend, zeigen, dass das kurze Jahrhundert, beginnend mit der Katastrophe des Ersten Weltkrieges, der sich daraus ergebende Totalitarismus und die Verwüstung durch den Zweiten Weltkrieg, in die Verleihung des Preises mündete. Allen BesucherInnen wurde damit klar, dass ein Europa des Friedens aus dem Gedenken an Verdun bis zum Vertrag von Lissabon (2009) geboren wurde. Diese Ausstellung integrierte die Vergangenheit als lebendige Dimension der Gegenwart.

Public Historians erreichen relevante öffentliche Ziele

Traditionell wurde Geschichte in der Staatsrhetorik, in der Politik und von Regierungen in Museen, Ausstellungen und sogar in Schulbüchern missbraucht. Interpretationen der Vergangenheit wurden verwendet, um Kriege und Völkermord, Rassismus, Anti-Globalisierungs-Haltungen und eine heroische nationale Geschichte zu rechtfertigen, die die Schatten der Vergangenheit ablehnt und eine patriotische Rhetorik fördert. Stattdessen kommunizieren Public Historians komplexere und “wissenschaftlich gesicherte” Vergangenheitsbewertungen an die Öffentlichkeit. Sie müssen unmittelbar in die Gedächtnispolitik und in die Aufwertung eines gemeinsamen kulturellen Erbes einbezogen werden. Sie müssen öffentliche Ziele erreichen und einen “öffentlichen Zweck” haben, indem sie den staatsbürgerlichen Wert von Geschichte als Beruf fördern.[16]

Abschließend möchte ich festhalten, dass ein Ziel von Public History darin besteht, mit und für die europäischen BürgerInnen originelle Forschung zu betreiben, ein weiteres darin, ein gemeinsames aktives Gedächtnis über die europäische Integration aufzubauen. Public History muss kritisch, partizipatorisch und in der Lage sein, eine Synthese für unsere gegenwärtige Zwickmühle zu finden, und sie sollte dazu beitragen, dass die europäische Geschichte zu einem integralen Teil unserer eigenen Identität wird.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Bottici, Chiara, and Benoît Challand. Imagining Europe, Myth, Memory and Identity. Cambridge: University Press, 2013.

- Kaiser, Wolfram, Stefan Krankenhagen, and Kerstin Poehls. Exhibiting Europe in museums: transnational networks, collections, narratives and representations. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014.

- Macdonald, Sharon. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. London: Routledge, 2013.

Webressourcen

- Inventing Europe, European Digital Museum for Science and Technology: http://www.inventingeurope.eu/ (letzter Zugriff 12.09.2017).

- House of European History, https://historia-europa.ep.eu/ (letzter Zugriff 12.09.2017).

- CVCE.eu by Uni.lu, https://www.cvce.eu/ (letzer Zugriff 12.09.2017).

_____________________

[1] Siehe die Finanzierungsinitiativen zur Stärkung der Erinnerung und der Bürgerbeteiligung auf institutioneller Ebene der EU. Gefördert von der EU-Kommission und organisiert durch die Verordnung (EU) Nr. 390/2014 des Rates vom 14. April 2014 (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2014_115_R_0002&qid=1398334046443) wurde das Programm “Europa für Bürgerinnen und Bürger” für den Zeitraum 2014-2020 ins Leben gerufen. Ziel dieses Programms ist es, zum Verständnis der EU, ihrer Geschichte und Vielfalt beizutragen; die Unionsbürgerschaft zu fördern und die Bedingungen für eine bürgerliche und demokratische Beteiligung auf EU-Ebene zu verbessern; das Bewusstsein für Erinnerung, gemeinsame Geschichte und Werte zu schärfen; die demokratische Beteiligung der Bürger auf EU-Ebene zu fördern…”EACA-Agentur (Exekutivagentur Bildung, Audiovisuelles und Kultur): Europa für Bürgerinnen und Bürger, URL: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/europe-for-citizens_en .

[2] “The history of the European Union,” in Europa.eu, https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/history_en

[3] Vgl. Inventing Europe, European Digital Museum for Science and Technology, das wichtige Projekt zur digitalen öffentlichen Geschichte, koordiniert vom niederländischen Historiker Johan Schot; vgl. auch Making Europe: Technology and Transformations, 1850-2000 (http://www.makingeurope.eu/), eine Buchreihe herausgeben von Johan Schot und Phil Scranton, Basingstoke: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2013-2018, http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14816.

[4] “In a new Focal Point, Eurozine seeks to broaden the question beyond the East-West historical divide. How are contested interpretations of historical and recent events made active in the present, both uniting and dividing European societies?”; see “Multilingual cultural e-zine that links up and promotes over 100 cultural journals from all over Europe,” Eurozine, 28 February 2011, http://www.eurozine.com/european-histories-concord-and-conflict/

[5] “…The European Union, itself the product of a number of predecessor institutions and treaties, represents the most sustained expression of a new quality of Europeanization since the Second World War….”; vgl. Wolfgang Schmale, “Processes of Europeanization,”European History Online (EGO), hrsg. the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2010-12-03, URL: http://www.ieg-ego.eu/schmalew-2010b-en URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-20101025144 [2017-08-28].

[6] Serge Noiret, “Public history as “useful history” before voting for Europe, May 22-25, 2014,”Digital & Public History, April 2014, http://dph.hypotheses.org/380 e “La Public History, una medicina necessaria nell’Union Europa oggi,” in Fondazione Feltrinelli; La nostra città futura, Agosto 1, 2017, http://fondazionefeltrinelli.it/la-public-history-medicina-necessaria-nell-unione-europea-oggi/.

[7] Sharon Macdonald: Memorylands: heritage and identity in Europe today (London, Routledge, 2013). “Memorylands […] provides new insights into how memory and the past are being performed and reconfigured in Europe […].” Die Konstruktion einer europäischen Identität wurde auch von der politischen Philosophin Chiara Bottici untersucht: “European Identity and the Politics of Remembrance,” in Karin Tilmans, Frank van Vree, and Jay Winter (eds.): Performing the past: memory, history, and identity in modern Europe (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010, pp. 335–359); Chiara Bottici and Benoît Challand: Imagining Europe, Myth, Memory and Identity (Cambridge University Press, 2013). Darüber hinaus spielen historische Museen eine Rolle beim Aufbau einer gemeinsamen europäischen Identität durch die “Museumifizierung” der Geschichte der europäischen Integration. Vgl. dazu Wolfram Kaiser, Stefan Krankenhagen and Kerstin Poehls: Exhibiting Europe in museums: transnational networks, collections, narratives and representations. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014. Vgl. auch Aline Sierp: History, Memory and Trans-European Identity: Unifying Divisions. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[8] Pierre Nora, Historien Public. Paris: Gallimard, 2011, pp. 446–447.

[9] Markus J. Prutsch, Research for CULT Committee – European Identity, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, IP/B/CULT/NT/2017-004, PE 585.921, April 2017, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/585921/IPOL_STU(2017)585921_EN.pdf. Dieses Strategiepapier folgt auf eine weitere Studie desselben Autors für das Europäische Parlament, Generaldirektion Interne Politikbereiche b: Struktur- und Kohäsionspolitik Kultur und Bildung, Kultur und Bildung, Kultur und Bildung: European Historical Memory: Policies, Challenges and Perspectives, 2013, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2013/513977/IPOL-CULT_NT(2013)513977_EN.pdf

[10] House of European History https://historia-europa.ep.eu/. European Parliament, House of European History: Guidebook to the Permanent Exhibition, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017, DOI 10.2861/348428.

[11] “Pour être mobilisateur, [le projet européen aujourd’hui] doit être soutenu par les citoyens européens. Seul son caractère populaire permettrait de confirmer et de souder la construction européenne.” See Frédéric Clavert: Narrating Europe : un exercice de réflexivité in Devenir historien-ne Méthodologie de la recherche et historiographie en master Histoire, URL: [http://devhist.hypotheses.org/2207].

[12] “Utopia is examined … as an expression of a concept of Europe and of being European which is critical of all forms of Eurocentrism and acknowledges the contribution of the other (in terms, for example, of race and gender) in the formation of the subject.” (Luisa Passerini. Memory and utopia: the primacy of intersubjectivity, London: Equinox, 2007, p. 8.)

[13] “The First World War is an important point of reference for the creation of a transnational and global historical consciousness, offering a unique chance to discuss the roots of and possibilities for European integration” in The First World War and European historical consciousness,” in World War One Goes World Wide Web, 8 October 2014 Brussels, http://www.1914-1918-online.net/res/A4_14-18_EU-Broschuere_CMYK_vd.pdf.

[14] Musée royal de l’Armée et d’Histoire Militaire: 14-18, It’s our History. Brussels, February 26, 2014 – April, 26, 2015., http://www.expo14-18.be/ die letzte verfügbare Version dieser Website wurde im Internetarchiv gespeichert 24. Februar 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160224063758/http://www.expo14-18.be/.

[15] 14-18 c’est notre histoire, https://tempora-expo.be/14-18-cest-notre-histoire/. Die Ausstellung fand von Februar 2014 bis November 2015 in Brüssel statt und zog mehr als 175.000 Besucher an.

[16] Solch eine aktive Rolle für den Public Historian wird vom britischen Historiker Alix Green in einem kürzlich erschienenen Buch über History, Politics and Public Purpose. Für Green ist ein Historiker nicht bloss ein Berater, wenn es um Geschichte geht. Green schreibt, Public Historians müssten “give moral, methodological and intellectual impetus to work in ways that contribute to public life and social welfare.” Alix R. Green: History, policy and public purpose: historians and historical thinking in government. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© Serge Noiret. Collage: Ein friedliches Europa.

Übersetzung

Dr. Mark Kyburz (homepage)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Noiret, Serge: Public History: Eine Notwendigkeit in der heutigen Europäischen Union? In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 32, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10113.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 32

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10113

Tags: Civics Education (Politische Bildung), European Union (Europäische Union), Language: French, Public History

Thank you Serge Noiret for this much-needed discussion on public history in the European Union. I agree that the resurgence of nationalistic narratives (not only in Eastern Europe though as demonstrated by some debates over the Brexit and the last French presidential elections) calls into question the public role of historians. I am not so sure though that we could oppose nationalistic uses of the past to “positive” public history practices.

Dictatorships have used forms of public practices to support their discourses of hatred. There have been many different uses and applications of history and public history.

What I agree on with Serge Noiret – and something I am sure he would have developed into a longer post – is the relevance of international public history practices. By enlarging our discussions and by involving partners beyond the nation-state, we can provide safer and more complex construction of the past. This is exactly what the House of History has been trying to do. Similar to the problematic debates in the United States over monuments, there is a need to see what has ben done beyond the national barriers, at the risk of missing broader transnational processes.

Another point I think Noiret is right about, is the need to empower the public. In order to fight Euro-skepticism (based partly on the mistrust towards top-down European politics), public history practitioners need to give a voice to the audiences, to share authority, and to empower groups who are often absent of the public discussions over the future of the EU. As Noiret says, inclusivity is key for public history in Europe. Again, I think this is an important article to lead the way to European practices of public history, bottom-up, inclusive, and transnational.

Les commémorations du centenaire de la Grande Guerre ont-elles véritablement, comme l’écrit Serge Noiret, “favorisé une meilleure connaissance et sensibilisation à l’égard des passés difficiles du continent et à l’identité commune européenne”? L’Europe n’a-t-elle pas été l’une des grande absentes de ces commémorations qui se sont avant tout déclinées sous un angle local, régional voire national? Au regard des contributions publiées notamment sur l’Observatoire du Centenaire (https://www.univ-paris1.fr/autres-structures-de-recherche/lobservatoire-du-centenaire/un-centenaire-mondial/), il est permis de douter de l’exercice.

En revanche, la trame narrative de la toute nouvelle Maison d’Histoire de l’Europe s’essaie, elle, bel et bien à l’exercice difficile de mise en évidence d’éléments de mémoire européenne. Cela ne signifie nullement gommer les différences au bénéfice d’un récit lisse et creux qui serait complètement aux antipodes des objectifs d’une histoire publique “efficace”. Présenter sous forme de “happy-end” un film sur l’attribution du Prix Nobel de la Paix à l’Union européenne en 2012 au sortir de l’exposition “14-18, c’est notre histoire”, n’est pas nécessairement la démarche la plus aboutie pour comprendre le cours 20e siècle et l’omniprésence de la violence.

Une Europe de la Paix est-elle vraiment née de la mémoire des champs de bataille de Verdun? La mémoire de ces champs de bataille n’a-t-elle pas aussi nourri la mémoire de “va-t-en guerre”, de revanche et de nouvelles violences? Où est le fil rouge de novembre 1918 à nos jours? Comment l’appréhender dans un questionnement et une approche qui intègrent des choix si différents de Londres à Berlin, d’Athènes à Rome, de Bruxelles à Sarajevo?

Un défi essentiel en termes d’histoire publique!