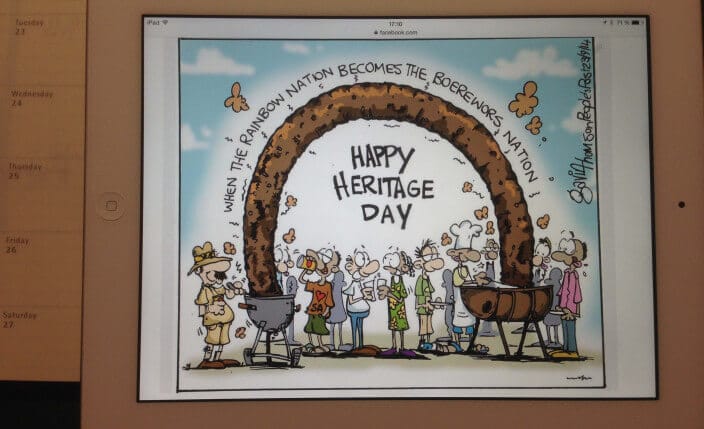

Abstract: 24 September is annually “Heritage Day” in South Africa. A Cape Town cartoonist conveyed greetings for the day in a cartoon he entitled “When the rainbow nation becomes the boerewors Nation.” It very effectively introduces some of the main issues that are raised by having a Heritage Day holiday in a country with multiple heritages.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2896.

Languages: English, Deutsch

24 September is annually “Heritage Day” in South Africa. A Cape Town cartoonist conveyed greetings for the day in a cartoon he entitled “When the rainbow nation becomes the boerewors Nation.” It very effectively introduces some of the main issues that are raised by having a Heritage Day holiday in a country with multiple heritages.

The Rainbow nation

Gavin Thompson has drawn a big boerewors sausage where a rainbow could be, stretching between the braaivleis of a white South African on the left of the picture and that of a black South African on the right side [braaivleis – South African barbeque, usually over a fire; to braai – to have a braaivleis; boerewors South African sausage, usually eaten at a braaivleis]. The cartoon also subtly shows the relative economic differences, as the white braaivleis is in a more expensive (but smaller) fire.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu[1] first called South Africans the “rainbow nation” in his enthusiasm to welcome a new South Africa which was no longer divided by race, but which celebrated its diversity. The term was quickly adopted both among those who were anxious to find a post-apartheid symbol for the country and those, like himself and Nelson Mandela,[2] who sought to promote reconciliation between people and a “new” South Africa. It became also a description of inclusiveness, to show that everyone was part of the nation and no-one was excluded. As such it was associated with the new flag and anthem and particular moments of celebration such as the inauguration of the President and sporting victories in the 1995 Rugby World Cup and 1996 African Cup of Nations football tournament, when the spirit abroad in the country was united as never before.

Heritage Day

The date chosen for Heritage Day is the date of Shaka day, which commemorates the death of Shaka Zulu, the Zulu king, in 1828. It may be seen as a gesture towards Zulu nationalists, many of whom were opposed to the African National Congress government taking over power in 1994. It also happens to have replaced on the calendar two former white South African public holidays and falls conveniently between their two dates. Settler’s Day (first week in September, abolished in 1979) celebrated in particular the contribution of English settlers to South Africa and Kruger Day (after Paul Kruger, President of the South African Republic 1883-1900; 10 October, abolished 1993). Thus, it consolidates a long association of the spring public holiday with cultural historical celebrations. But it was deliberately not called Shaka Day, in an attempt to create the space for all South Africans to show regard for both their own heritages and to facilitate a post-apartheid vision of a common heritage for all.

The concept of a “National Braai Day” on Heritage day, conceived by a white South African in 2005, but backed, for example, by Desmond Tutu, is to use the social custom of the braai, common to many South Africans (as the cartoon shows) on that day, “to unite around fires, share our heritage and wave our flag on 24 September every year.”[3]

Reconciliation and nation building

Heritage Day draws on narratives of reconciliation and nation-building, both of which are still widely accepted and proudly identified with by most South Africans, albeit for a range of different reasons. The relationship between them is complex. At its most heartfelt is the sense that nation-building is founded on reconciliation: that there would not have been a “new” South African nation without there having been significant moments of reconciliation between South African leaders, which have been shared by the population at large. Reconciliation also implies restoration and the opportunity to begin afresh, discarding some of the old and looking ahead on strength of hope of the new. It offers the chance of a new identity, a new sense of pride and a new birthright. But nation-building can also be at the expense of reconciliation. It can easily be corrupted to serve party political purposes and can be employed without much concern for minorities (of whatever kind). Any attempt by any group or “culture” to push hard for its view of heritage or its way of celebration is likely to cause offence and division.

And now

Where, then, was South Africa on 24 September 2014? If the promotions in the newspapers were anything to go by, more South Africans than ever were buying meat to braai, which must imply greater adoption of this version of “heritage”, though it would still be more popular among white South Africans.[4] Most South Africans could be found in three different groups: those who were grateful to have a holiday but not inclined to want to celebrate it, those who appropriated the day to mark a particular cultural or sporting celebration and those who were happy to follow the lead of politicians and unionists and attend rallies or view on television what they provided in their own brands of “nation-building” events. Museums and national parks have appropriated the day and offer free or cheap access on it. All media give space or time to the idea of heritage and encourage discussion and contributions about what it means, hoping to keep alive elements of the rainbow.

The rainbow replaced by a sausage is both a reminder that after 20 years of democracy a shared common heritage is still a long way away and a comment that it might be more worthwhile to find simple commonalities rather than to try and construct more complex cultural understandings. While “Heritage Day” celebrates an unspecified heritage, its virtue is that it allows the space for both discussions to take place.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Alex Boraine, “A Country Unmasked: Inside South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” Oxford University Press 2001.

- Richard A. Wilson, “The Politics of Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa,” Cambridge University Press 2001.

- Nigel Worden, “Making of Modern South Africa: Conquest, Segregation and Apartheid,” Wiley Blackwell 2000.

Web Resources

- South African History Online website. Heritage Day: http://www.sahistory.org.za/cultural-heritage-religion/national-heritage-day (last accessed 10.11.2014).

- South African Government website: http://www.gov.za/heritage-day (last accessed 10.11.2014).

- Examples of media description of Heritage Day: http://www.capetownmagazine.com/public-holiday-heritage-day; http://www.southafrica.info/news/heritage-day.htm#.VEkMuL5BvtQ (last accessed 10.11.2014).

____________________

[1] Article: Archbishop Emeritus Mpilo Desmond Tutu. http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/archbishop-emeritus-mpilo-desmond-tutu (last accessed 07.11.2014).

[2] ‘Statement of the President of the ANC Nelson R. Mandela at his inauguration as President of the Democratic Republic of South Africa Union buildings Pretoria, 10 May 1994’. http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/statement-president-anc-nelson-r-mandela-his-inauguration-president-democratic-republic-sout (last accessed 07.11.2014).

[3] National Braai Day ‘Our mission’. http://braai.com/national-braai-day-mission/ (last accessed 07.11.2014).

[4] See, for example, the opinion of Asanda Ngoasheng, “Heritage not about braaivleis” Cape Times, 25 September 2014. http://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/heritage-not-about-braaivleis-1.1755999#.VEkNpL5BvtQ (last accessed 07.11.2014).

_____________________

Image Credits

© Gavin Thompson/ africartoons.com.

Recommended Citation

Siebörger, Rob: What Heritage Day? In: Public History Weekly 2 (2014) 39, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2896.

Am 24. September ist jährlich der “Kulturerbe-Tag” in Südafrika. Ein Cartoonist aus Kapstadt gestaltete anlässlich dieses Tages eine Grußkarte unter dem Motto “Wenn die Regenbogennation zur Würstchennation wird”. Dies lenkt den Fokus deutlich auf die Debatte, die daher rührt, dass eine Nation mit vielfachem kulturellen Erbe einen “Kulturerbe-Tag” feiert.

Die Regenbogennation

Gavin Thomson malte ein großes boerewors-Würstchen an die Stelle, an der eigentlich ein Regenbogen stehen könnte, der sich als Brücke zwischen den braaivleis des weißen Südafrikas auf der linken Seite und denen des schwarzen Südafrikas auf der rechten Seite versteht [braaivleis – südafrikanisches Barbeque, normalerweise über einem offenen Grill; braai = grillen, braavleis = ein Grillfest veranstalten; boerewors = südafrikanische Würstchen, die bei einem braavleis gegessen werden]. Der Cartoon zeigt subtil die vorhandenen ökonomischen Differenzen, die sich anhand des weißen Grills ablesen lassen, der teurer scheint (aber auf kleinerer Flamme grillt).

Erzbischof Desmond Tutu[1] war der erste, der von einer “Regenbogennation” sprach – beseelt von seinem Enthusiasmus, ein neues Südafrika zu begrüßen, das nicht länger durch Rasseneinteilung geteilt ist und in dem Verschiedenheit gelebt wird. Der Ausdruck wurde schnell adaptiert, sowohl bei jenen, denen es darum ging, ein Symbol der Post-Apartheit zu finden, als auch denen, die wie er selbst und Nelson Mandela,[2] nach einer Versöhnung zwischen den Menschen und einem “neuen” Südafrika strebten. Es wurde daneben auch zu einem Symbol der Inklusion, das zeigte, dass jedermann Teil dieser Nation ist und niemand ausgeschlossen wird. So wurde es auch in der neuen Flagge und der Hymne aufgegriffen und bei Gelegenheiten wie der Einführung des Präsidenten und sportlichen Ereignissen wie dem Rugby World Cup 1995 und der Fußball-Afrikameisterschaft 1996 verwendet; der Geist dieses Symbols zeigte dem Ausland eine bis dahin nie gekannte, geeinigte Nation.

Der Kulturerbe-Tag

Das Datum, das für den Kulturerbe-Tag gewählt wurde, entspricht dem Datum des Shaka-Tags, dem Todestag des Zulu Königs Shaka Zulu im Jahr 1928. Es kann als eine Geste in Richtung der Zulu-Nationalisten gesehen werden, von denen viele gegen die Regierungsübernahme des Afrikanischen Nationalkongresses im Jahr 1994 waren. Dazu kommt, dass der Feiertag zwei frühere “weiße” südafrikanische Feiertage ersetzte und sich bequemerweise genau zwischen diesen beiden Daten einreihte. Der Settler-Tag (in der ersten Septemberwoche, abgeschafft im Jahr 1979) gedachte dem Beitrag der englischen Siedler, die nach Südafrika kamen, und der Kruger-Tag gedachte Paul Kruger, dem Präsidenten der südafrikanischen Republik zwischen 1883 und 1900 (10. Oktober, abgeschafft 1993). Auf diese Weise konsolidierte sich neben den Feiertagen im Frühjahr ein kulturgeschichtlicher Feiertag. Bewusst entschied man sich nicht für den Shaka-Tag. Man versuchte, eine Gelegenheit zu schaffen, die Raum für alle SüdafrikanerInnen bot, ihres kulturellen Erbes zu gedenken und eine Post-Apartheit-Version des gemeinsamen Erbes für alle zu ermöglichen.

Das Konzept eines “Nationalen Grilltags” im Rahmen des Kulturerbe-Tags wurde von einem weißen Südafrikaner im Jahr 2005 entwickelt. Festgestellt werden kann der soziale Gebrauch des Tages als beliebter Grilltag vieler SüdafrikanerInnen (wie auch der Comic zeigt), und wird zum Beispiel auch durch die Aussage Desmond Tutus belegt, dass “wir uns am 24. September jährlich an Feuern vereinen, unseres gemeinsamen Erbes gedenken und unsere Flagge wehen lassen.”[3]

Versöhnung und Nationenbildung

Der Kulturerbe-Tag basiert auf Narrationen von Versöhnung und der Nationenbildung, die beide allgemein akzeptiert sind und mit denen die meisten Südafrikaner sich stolz identifizieren, wenn auch aus verschiedenen Gründen. Die Beziehung zwischen beiden ist komplex. Am innigsten ist das Gefühl, dass die Nationenbildung auf Versöhnung basiert: Dass es keinen “neuen” südafrikanischen Staat geben würde ohne die massgebliche Aussöhnung zwischen den südafrikanischen FührerInnen, ist eine weitverbreitete Ansicht in der Bevölkerung. Versöhnung bedeutet auch Wiederherstellung und die Gelegenheit, neu zu beginnen. Dabei wird einiges verworfen, dafür aber hoffnungsvoll nach vorne geschaut. Es bietet die Chance einer neuen Identität, ein neues Gefühl des Stolzes und ein neues Geburtsrecht. Aber die Nationenbildung kann auch auf Kosten der Versöhnung gehen. Sie kann leicht korrumpiert werden, parteipolitischen Zwecken dienen und ohne viel Mühe von Minderheiten (oder sonst wem) ausgenutzt werden. Jeder Versuch einer Gruppe oder einer “Kultur”, ihre Sicht auf das kulturelle Erbe konsequent durchzusetzen oder die Art und Weise, es zu feiern, vorzuschreiben, kann auch zu Widerstand und Teilung führen.

Und nun?

Wo also war Südafrika am 24. September 2014? Legt man die Werbeanzeigen in den Zeitungen zugrunde, dann kauften mehr Südafrikaner als je zuvor Fleisch für ihr braai, was eine großzügige Auslegung einer Version “kulturellen Erbes” nahelegt, nach der vor allem weiße SüdafrikanerInnen den Feiertag schätzen.[4] Die meisten SüdafrikanerInnen lassen sich einer der folgenden drei Gruppen zuordnen: diejenigen, die froh um den Feiertag sind, ihn aber nicht feiern wollen; diejenigen, die den Tag dafür nutzen, an diversen Sport- und Kulturveranstaltungen teilzuhaben; sowie diejenigen, die froh darüber sind, die Reden der PolitikerInnen und GewerkschafterInnen verfolgen zu können, sei es durch Teilnahme an Versammlungen oder im Fernsehen, wo diese ihre Sicht der “Nationenbildung” verbreiten. Museen und Nationalparks gingen dazu über, an diesem Tag freien oder vergünstigten Eintritt zu gewähren. Alle Medien räumen der Idee des Kulturerbe-Tages Platz oder Zeit ein, um durch Diskussionen und Beiträge die Hoffnung auf die Elemente der Regenbogennation aufrechtzuerhalten. Der durch eine Wurst ersetzte Regenbogen ist eine Erinnerung daran, dass nach 20 Jahren der Demokratie es noch immer ein weiter Weg zu einem gemeinsamen kulturellen Erbe ist und ein Beitrag dazu, dass es unter Umständen wichtig sein könnte, einfache Gemeinsamkeiten zu finden, anstatt ein überkomplexes kulturelles Verständnis zu schaffen. Während der “Kulturerbe-Tag” ein unspezifisches Erbe feiert, ist es seine immanente Tugend, beiden Diskussionen Raum zu bieten.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Boraine, Alex: A Country Unmasked: Inside South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Oxford 2001.

- Wilson, Richard A.: The Politics of Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa. Cambridge 2001.

- Worden, Nigel: Making of Modern South Africa. Conquest, Segregation and Apartheid. Wiley 2000.

Webressourcen

- South African History Online. Heritage Day: http://www.sahistory.org.za/cultural-heritage-religion/national-heritage-day (zuletzt am 07.11.2014).

- Offizielle Regierungsseite zum Heritage Day: http://www.gov.za/heritage-day (zuletzt am 07.11.2014).

- Beisipielhafte Verwendung des Heritage Days in den Medien: http://www.capetownmagazine.com/public-holiday-heritage-day; http://www.southafrica.info/news/heritage-day.htm#.VEkMuL5BvtQ (zuletzt am 10.11.2014).

____________________

[1] Vgl. den Artikel über den emeritierten Erzbischof Mpilo Desmond Tutu. Online unter: http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/archbishop-emeritus-mpilo-desmond-tutu. (zuletzt am 07.11.2014).

[2] Statement des ANC Vorsitzenden Nelson R. Mandela im Rahmen seiner Einführung als Präsident der Demokratischen Republik von Südafrika in Pretoria, 10.05.1994. Online unter: http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/statement-president-anc-nelson-r-mandela-his-inauguration-president-democratic-republic-sout. (zuletzt am 07.11.2014).

[3] National Braai Day ‘Our mission’. Online unter: http://braai.com/national-braai-day-mission/ (zuletzt am 07.11.2014).

[4] Vgl. Z.B. die Auffassung Asanda Ngoashengs, “Heritage not about braaivleis”. In: Cape Times, 25. September 2014. Online unter: http://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/heritage-not-about-braaivleis-1.1755999#.VEkNpL5BvtQ. (zuletzt am 07.11.2014).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© Gavin Thompson/ africartoons.com.

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen

von Marco Zerwas

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Siebörger, Rob: Welcher Kulturerbe-Tag? In: Public History Weekly 2 (2014) 39, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2896.

Copyright (c) 2014 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 2 (2014) 39

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2896

Tags: Africa, Anniversary (Jubiläum), History Politics (Geschichtspolitik), South Africa (Südafrika)

The Boerewors Braai – dimension of heritage is the nearest that neo-liberalism could sqeeze out of this conceived holiday. Like most other “national holidays” in South Africa, the historical significance is distorted and redefined – June 16 (Soweto) as: Youth Day; Sharpville day as: Human Rights day etc. In fact Heritage day was already renamed “National Braai day” and promoted by leading supermarket chains in South Africa. Just everything has to be commodified – even culture. Hence the focus is now on braai (barbeque) which will provide an extra boost to retail sales figures.

Heritage should be subjected to critique of the present in terms of its past. Not every South African accept that all is well with “reconciliation” or that “nation-building” is progessively growing as the Springboks are winning (or loosing?). My view is that the historical jump from oppression to the rainbow was opportunistic and a nation cannot be build with a majic wand which ignores history. This play with the past and the reconfiguration of historical space for small financial gains should be opposed with rigorous debate of the colonial legacy that merrily continues with the dominant barbeque culture – aptly coined wors culture (sausage) which in Afrikaans can metaphorically mean “idiotic/stupid culture”!

Rainbows and Black Pete’s. On heritage debates in the Netherlands and South Africa

Dutch national television (November 2014): white Pete interviewed before turning black

Rob Siebörgers contribution on South Africa’s National Braai Day as a renegotiation of older heritage reminds of a current public controversy in the Netherlands. It concerns one of the most cherished Dutch national traditions: the annual feast of Sinterklaas and his Black Pete’s. It is a debate about inclusion and colour in an attempt to renegotiate strong emotions on all sides and it affects what is learned in schools about the past.

The Dutch, of course, are South Africa’s former colonizer. Dutch involvement started from 1652 with the building of a fort at the Cape of Good Hope and continued – with a short interval – until 1806, when England took over the colony. One of the Dutch contributions to the gradually expanding colony was the introduction of slavery, already in the 17th century. Slaves were imported from the Indian Ocean coasts, including Madagascar. Around 1700, the number of slaves overtook the number of European settlers. In the Netherlands, this particular history of slavery has largely been ignored, but the Dutch introduction of slavery across the Atlantic now becomes a haunting memory. This past is easily invoked by Dutch citizens of Caribbean descent to explain present manifestations of racism in social media and Dutch society at large. To make this point the annual feast of Sinterklaas and his Black Pete’s is a dream target.

In essence, the Sinterklaas tradition is a simple story: every year in November, an old, white bishop from Spain arrives in the Netherlands, carrying presents and candy for the children. He rides a white horse and is escorted by figures with brown and black faces in colourful suits: the black Pete’s. During their stay, children will put a shoe near the chimney or the windows of their homes with some food for the horse and they will sing songs in honour of Sinterklaas. The next morning – mysteriously- the food is gone and a small present has been left. Finally, on the 5th of December, Sinterklaas brings many more presents for all children. Sinterklaas and his Black Pete’s also visit schools. Usually children believe the story until they are 7 or 8 years old, but usually celebrations continue after that age.

Today, this tradition is perceived as either an innocent children’s party or a racist tradition, with origins in the Dutch transatlantic slavery past. Both sides seem historically partly wrong and contribute their contemporary concerns to the debate. For those steeped in memories of slavery and American black face debates and perhaps film culture (cfr. D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation of 1915), Sinterklaas cannot be other than a white suppressor. So far, this seems carrying the tragedies and emotions of one particular context to another. But activists are undoubtedly right that the Black Pete for long had and sometimes still has the appearance of a racist stereotype, with curly hair, big red lips and earrings. The radical positions then are as follows: this heritage should be abolished altogether or be continued without black Pete’s (activists inspired by American debates on racism) or the tradition should be frozen at this point in time and be enlisted as endangered heritage (the political party of Islam-basher Geert Wilders).

While writing, however, national television has started a process of renegotiation. In the daily broadcasted Sinterklaas-news (for the children), the story, as it is now narrated, emphasizes that the colour of Pete’s is unimportant. It has introduced Pete’s of different colours (although many are still black) and has explained why Pete’s are black: the traditional story of Pete’s going through chimney’s and turning black. As the National Braai Day is an attempt to unite contested images of the nation by carefully choosing dates and names, the Dutch story now unfolding on national television ingeniously invokes Dutch heritage to bridge the gap. The first white Pete on the Sinterklaas-news is named after a character (Jan Salie) in a story of 1842 by a well known Dutch writer (E.J. Potgieter). The character’s name symbolizes lethargy and a lack of courage and vitality. After the white Pete had jumped through a large chimney several times last week, he became black and received a new name. It is unclear what exactly the message was, except that adaptations are needed. Embracing a dynamic concept of heritage, the makers of the Sinterklaas-news even referred to the rainbow as a place where some Black Pete’s were going.

Both Dutch and South African societies show that – although a point of no return in a tradition has been passed – there will be no easy closure of the debate. Heritage, in the end, is always more about the present than about the past. When such traditions enter school, history teachers may feel like having conflicting roles. Joining the tradition is expected, but so is critically questioning the past, addressing attention to multiple perspectives and thinking through contemporary ways of tailoring the past to present concerns. We all encounter heritage all the time, but in a democratic society we may not be blind for how and why it is made.

Literature on research on Dutch history teaching and heritage education

– Klein, S., Grever, M. and Van Boxtel C., ‘Zie, denk, voel, vraag, spreek, hoor en verwonder. Afstand en nabijheid bij geschiedenisonderwijs en erfgoededucatie in Nederland’, Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 124 (2011) 381-395.

– Savenije, G. Sensitive heritage under negotiation. Pupils historical imagination and attribution of significance while engaged in heritage projects (PhD thesis Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2014).

– De Bruijn, P., Bridges to the past. Historical distance and multiperspectivity in English and Dutch heritage educational sources (PhD thesis Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2014).

– Grever, M. and Van Boxtel, C., Verlangen naar tastbaar verleden. Erfgoed, onderwijs en historisch besef (Hilversum 2014). ISBN 9-789087-044626

Literature on the influence of D.W. Griffith’s movie and racism

– Melvyn Stokes, D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. A History of the most controversial motion picture of all time (Oxford 2008).