Abstract: The term ‘Britain’ refers to both an island with a continuous history stretching back to the last Ice Age and a more recent constitutional arrangement. Given these meanings – and the context of Brexit and Scottish independence movements – the use of the word ‘Britain’ in curriculum documents is never neutral. This article examines the pre-university history examination syllabuses in England and Scotland and finds ‘Britain’ used differently in each: geographically in Scotland and constitutionally in England. The paper explores these uses and the implicit narratives they create.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21664

Languages: English

What do we mean when we say ‘Britain’? Is Britain an island formed 8000 years ago by rising sea levels in the English Channel? Or is ‘Britain’ a multi-national state united by a single government in London? The answer is, of course, both – although the latter is too simple, since there are governments at least three of the UK’s four component jurisdictions.[1] Nevertheless, the contexts in which the term ‘Britain’ is favoured over, say, ‘England’, ‘Scotland’ or ‘the UK’ reveals much about the assumptions underlying this use. In this article, we explore this use in the context of the examination syllabuses of England and Scotland and find that the concept ‘Britain’ is called-up in different times in different places.

Different Britains

The United Kingdom is a multi-national state made up of four jurisdictions, which have their own histories and educational authorities.[2] In their history curricula, each component jurisdiction must manage two levels of identity – identity at the level of the UK as a whole and identity at the local level. In this short article, we explore these issues through the prism of two of the component education systems of the UK – the Scottish and the English – and through the prism of pre-university national examinations in both contexts.

Our analysis shows that ‘Britain’ is conceived differently in English and Scottish curricula. In England, ‘Britain’ is understood constitutionally as coterminous with ‘the United Kingdom’, the nation created in 1707 by the union of Scotland and England. In this framing, ‘Britain’ (the UK) simply supersedes ‘England’ as the nation where English people live. This approach – which we term ‘the continuity narrative’ pays little attention to Scotland either before or after the 1707 union.

The Scottish curriculum, meanwhile, understands the word ‘Britain’ geographically to refer to the island of Great Britain. In this framing, the Scottish nation both existed before the formation of the UK in 1707 and persists after its formation, meaning that the curriculum tells two simultaneous stories, that of Scotland and that of Britain. We refer to this approach as a ‘split screen narrative’, and suggest that it creates no fewer tensions and contradictions than its English alternative.

Nation-state / Nation-place: When was Britain?

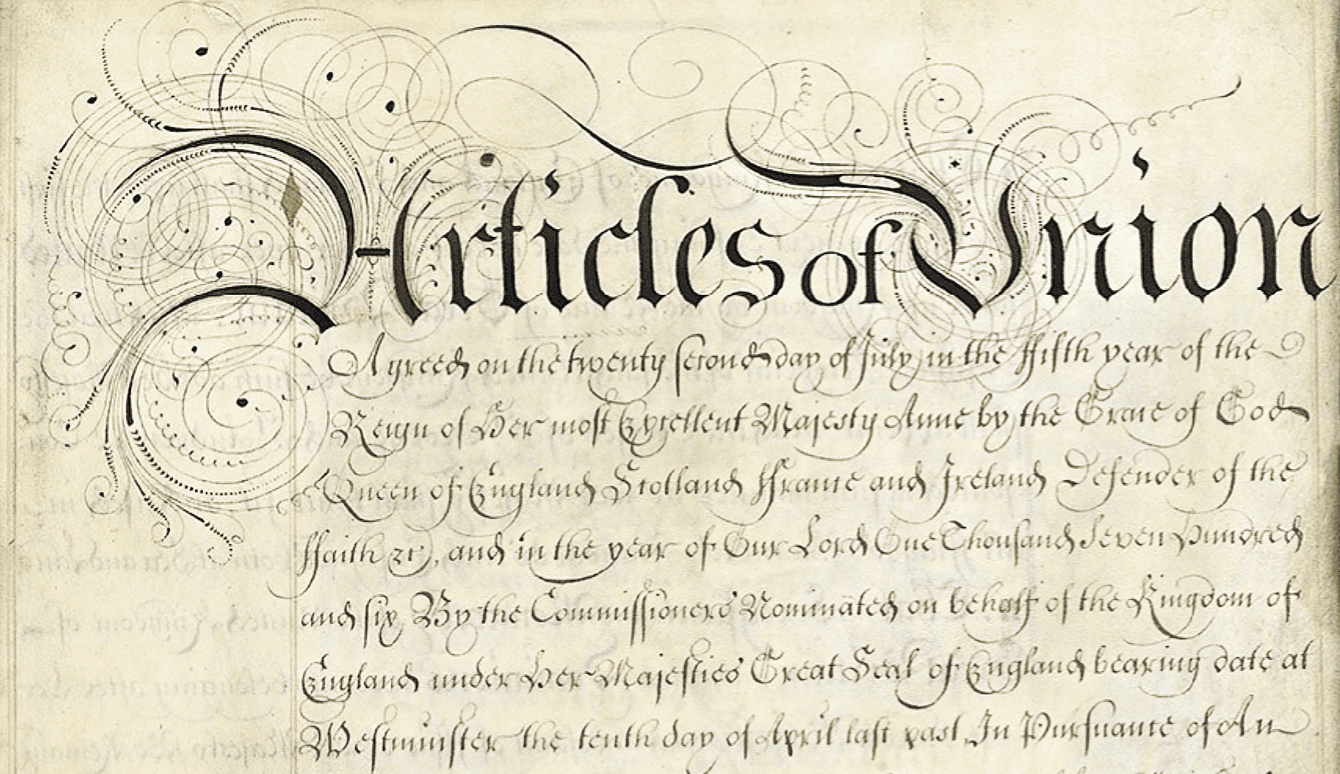

Great Britain is an island – the largest in its archipelago. The island Great Britain was separated from Europe 8000 years ago by rising sea levels. The political entity the United Kingdom was formed in 1707 with the Treaty of Union uniting England and Scotland, modified in 1801 by the incorporation of the Island and Ireland, reduced, in 1922, to the six counties of Ireland not included in what is now the Republic of Ireland. Given these facts, and the desire of national educational jurisdictions within the United Kingdom (UK) to maintain national histories, questions of terminology become vital, are never neutral and are rarely straightforward.

The island of Britain has been inhabited for thousands of years and so its ‘history’ clearly precedes those of the nations which comprise it. But nations in this island – Wales, Scotland and England – all have national histories which deserve attention. However, these nations all subsequently lost their independence – is the independent Scotland of 1500 the ‘same thing’ as the Scotland which part-comprises the UK? Opinions on this matter are passionate and divisive. For some, the ‘British state’ is an imposition on Welsh, English or Scottish national identities which should be preserved in defiance of single homogeneous ‘British identity.’ For others, the creation of the UK forged a single new identity which rendered previous national identities obsolete.[3]

Education in the UK

A comparison of the school curricula of the countries of the United Kingdom is a useful lens to explore these contested identities. The UK has never had a shared educational system and significant differences are apparent between the Scottish and English approaches to education.

In Scotland, pre-university qualifications (known as Highers) emphasise breadth of study. Higher courses are just one year long, but students are expected to study these in at least five subjects. In England, meanwhile, the emphasis is on depth of study – prospective university students study just three A-Level subjects for two years. Both countries have highly centralised qualifications system in which students take examinations in specific subjects. These examinations are devised and assessed by external bodies operated under government licence. In Scotland just one organisation (the Scottish Qualifications Authority) holds this licence, while in England four ‘examination boards’ are licenced, with schools empowered to choose between these.

Our research uses a surface-level analysis of the overall structure of the SQA Higher Syllabus and the OCR A-Level Syllabus to explore the way in which ‘Britain’ is understood. The history syllabuses of the two countries are structurally similar with schools able to choose which topics to teach from a menu of options. In neither country, however, do schools have complete freedom of choice, rather the syllabus steers students to ensure a ‘balance’ in what is studied.

| Scottish Higher

Schools must study one topic from each list |

OCR A-Level

Schools must study one topic from each list |

| British History | A British Period Study |

| European and World History | A non-British Period Study |

| Scottish History | Thematic Study and Historical Interpretations |

Table 1. Curriculum Architecture in England and Scotland[4]

A difference is immediately apparent. In England, historical topics are divided simply into ‘British History’ and ‘non-British History’; while in Scotland, a third category – ‘Scottish History’ is identified. The remainder of the paper looks at the implications of these two approaches.

The ‘Split-Screen’ and the ‘Continuity State’

The table below shows the ‘British’ and ‘Scottish’ unit titles arranged chronologically. As discussed above, the Scottish curriculum identifies both ‘Scottish History’ topics and ‘British History’ topics, while the English syllabus identifies just ‘British topics’ (OCR, 2021).

|

Time |

English Syllabus options for ‘British’ Units (OCR) |

Scottish Syllabus (SQA) |

|||

|

Options for ‘Scottish’ Unit |

Options for ‘British Unit’ |

||||

|

1000 |

Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 1035-1107 |

Church, State and Feudal Society, 1066-1406 |

|||

|

1100 |

|||||

|

1200 |

England 1199-1272 |

The Wars of Independence, 1249-1328 | |||

| 1300 |

England 1377-1455 |

||||

|

|

|||||

| 1400 |

England 1445-1509 |

||||

|

England 1445-1558 |

|||||

| 1500 |

Age of Reformation, 1542-1603 |

||||

| England 1547-1603 | |||||

| 1600 | The Early Starts and the Origins of the Civil War 1603-1660 |

The Century of Revolutions, 1603-1702 |

|||

|

1700 |

The Making of Georgian Britain, 1678-1760 |

The Treaty of Union, 1689-1740 |

|||

|

The Atlantic Slave Trade (18th Century to 1807) |

|||||

|

1800 |

From Pitt to Peel: Britain 1783-1853 |

||||

|

Migration and Empire, 1830-1939 |

Britain, 1851-1951 |

||||

| 1900 |

Liberals, Conservatives, and the Rise of Labour, 1846-1918 |

||||

|

Britain and Ireland, 1900-1985 |

|||||

|

Britain 1900-1951 |

|||||

|

Britain 1930-1997 |

|||||

Table 2: Pre-University Curricula in England and Scotland[5]

Table 2 reveals some striking contrasts between the English and the Scottish curricular approaches, the English curriculum presenting what we have called a ‘Continuity State’ narrative and the Scottish curriculum presenting what we have called a ‘Split-Screen Approach’.[6]

We call the English approach a ‘continuity’ approach because it presents one continuous development over time, covering almost all of the thousand-year period covered in Table 2 without interruption. There is ontological as well as temporal continuity – before 1603, almost all the unit titles refer to ‘England’ and after 1603 almost all the unit titles refer to ‘Britain’ – an English line of development merges into a British one that, in effect, an approach that creates the impression of a continuous story. England simply morphs into Britain. Meanwhile, Scotland is not explicitly mentioned before England becomes Britain, through the Act of Union (1707), after which point neither ‘England’ nor ‘Scotland’ are mentioned in unit headings.

We call the Scottish approach a ‘split-screen’ approach, by contrast, for the reasons that the columns suggest. Scottish and British history are posited as discrete and distinct things and they continuously remain so, before and after the Treaty of Union.

There are perplexing features in both approaches. We have already mentioned the absence of Scotland in the English unit titles in Table 2. Given this absence, what it is that causes England to morph into Britain remains opaque – it is as if there were only one English dimension involved.

The Scottish case raises two perplexities also – on the one hand, the question of change and on the other a principle of allocation. What did the Act of Union change, one might ask, if the screen remains resolutely split after it? It is as if nothing changed in the ontological status of Scotland, even though the Scottish Parliament went into abeyance in 1707, returning only in the 1990s (not covered here) after devolution. In terms of allocation, one might ask, what makes the Union only a Scottish topic (since Britain is created through it and a union must merge at least two entities)? Other questions similarly arise – why, for example, is the Slave Trade – vital to the fortunes of cities like Glasgow – solely British and not Scottish and global?

Explanations for Perplexities

We can only expect so much from history curricula. One cannot expect those who devise outline contents for schools to teach – at least not in democratic contexts where difficulties have be negotiated and compromises reached – to resolve conceptual challenges and complex questions that the polities and societies they are in have not managed to clarify and solve.

We have to distinguish between two planes of reality, perhaps – what we have called ‘curriculum neatness’ (an ideal to aspire to a requirement of curriculum architecture) and ‘political messiness’ (a fact of life in any complex context). As any observer of politics in the United Kingdom since the second half of the twentieth century will have noticed, the ‘national’ question is a very live one – as works such as Nairn’s Breakup of Britain[7] have demonstrated and as recent events such as the 2014 Referendum on Scottish Independence and the differential voting in Scotland and England in the Brexit Referendum underlined.[8]

At least two possible explanations for perplexities that we have mentioned. We have called these ‘accidental’ imprecision’ and ‘intentional equivocation.’[9] Both these explanations must remain speculative, since we are working back solely from curriculum texts to what may explain their features in their contexts of production. Accidental imprecision may explain these perplexities simply as a function of the general lack of clarity about terminology in social, cultural, and political discourse in the United Kingdom. Equivocation relates to deliberate ambiguity.

It is entirely possible that those who create public examinations find the vagueness and imprecision about nations and nationalities within the UK useful, since it absolves them of a controversy-provoking task of appearing to arbitrate about where Scotland, England and Britain begin and end.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Chapman, A. and Smith, J.. ‘Narration and Equivocation: Locating State, Nation and Empire in the Pre-university History Examination Syllabuses of England and Scotland’ forthcoming in Piero S. Colla and Andrea Di Michele (Eds.) History Education at the Edge of the Nation: Political Autonomy, Educational Reforms, and Memory-shaping in European Periphery. London: Palgrave 2023.

- Smith, J.. Identity and Instrumentality: History in the Scottish School Curriculum, 1992-2017. Historical Encounters: A journal of historical consciousness, historical cultures, and history education, 5(1) 2018, 31-45.

- McCrone, D.. Understanding Scotland: the sociology of a stateless nation. London: Routledge 1992.

Web Resources

- OCR’s A Level History Curriculum: https://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/170128-specification-accredited-a-level-gce-history-a-h505.pdf (last accessed 12 June 2023).

- The Scottish Higher Curriculum for History: https://www.sqa.org.uk/files_ccc/HigherCourseSpecHistory.pdf (last accessed 12 June 2023).

- The Encyclopaedia Britannica’s entry on The United Kingdom: https://www.britannica.com/place/United-Kingdom/Plant-and-animal-life (last accessed 12 June 2023).

_____________________

[1] We say ‘at least three’ since there is a Scottish government in Scotland, a Welsh government in Wales and a Northern Irish government in Northern Ireland but there is only a British government in London, not an English one.

[2] This article draws heavily on, and partially reproduces, the analysis reported in our paper ‘Narration and Equivocation: Locating State, Nation and Empire in the Pre-university History Examination Syllabuses of England and Scotland’ forthcoming in Piero S. Colla and Andrea Di Michele (Eds.) History Education at the Edge of the Nation: Political Autonomy, Educational Reforms, and Memory-shaping in European Periphery, to be published by Palgrave in June 2023.

[3] A dramatic example of the latter position was provided in comments by former ‘Brexit’ negotiator Lord Frost in August 2022. https://nation.cymru/news/wales-and-scotland-not-nations-and-independence-should-be-made-impossible-says-lord-frost/

[4] There are three bodies offering equivalent public examinations in England and one such body in Scotland. In addition, English schools can follow a syllabus created by the Welsh exam board. In this table, therefore, we select one representative English case to compare with the Scottish case.

[5] Chapman, A. and Smith, J. ‘Narration and Equivocation: Locating State, Nation and Empire in the Pre-university History Examination Syllabuses of England and Scotland’ forthcoming in Piero S. Colla and Andrea Di Michele (Eds.) History Education at the Edge of the Nation: Political Autonomy, Educational Reforms, and Memory-shaping in European Periphery, to be published by Palgrave in June 2023.

[6] Ibid

[7] Tom Nairn, The Break-up of Britain, 2nd ed. (London: Verso Books, 1981).

[8] The Electoral Commission’s Report on the Scottish Independence Referendum can be read here – https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/elections-and-referendums/past-elections-and-referendums/scottish-independence-referendum/report-scottish-independence-referendum. Maps showing the national distribution of the ‘Leave’ and ‘Remain’ votes in the Brexit Referendum can be viewed here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-36616028.

[9] Chapman and Smith, op cit.

_____________________

Image Credits

The Articles of Union (1707), Public Domain.

Recommended Citation

Smith, Joe, Arthur Chapman: When was Britain? Answers from Scotland and England. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 5, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21664.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 5

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21664

Tags: England, Identity (Identität), National Identification (Nationale Identifikation), Scotland, UK (Grossbritannien)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

The inevitability of an epistemic rupture

That an epistemic rupture would emerge between English and Scottish curricular accounts of their shared history is unsurprising. This is particularly so in the context of Scottish transgenerational or historical trauma related to English hegemony and associated power asymmetries, and more contemporary phenomena, like Brexit and the Scottish Independence Movement. Additionally, Scotland and England are different nations meaning that their independent nation-building and citizenship formation goals are likely underpinned by different ideologies and agendas. This is pertinent as curricula are shaped by these very ideologies, that is, the knowledge, values and worldviews of political elites, including governments and other national institutions (among other factors).[1] These ideological agendas are grounded in and rely upon highly selective versions of the past, which (re)inscribe hegemonic nationalistic narratives.[2]

Given the propensity of political elites to construct “positive, nationalistic view[s] of the past”,[3] that two nations’ accounts of the same history and the meanings they attach to key contested concepts (like ‘Britain’) is to be expected. Thus, while unsurprised by the divergences between both curricula, I found the authors’ analysis very interesting and now offer some reflections on the article’s content.

In the context of the English Syllabus options for ‘British’ units (OCR), the terminology used serves to de-politicise and santise England’s history, and as the authors theorise, to present a ‘Continuity State’ narrative. In Staeheli & Hammett’s[4] words, when speaking about education more broadly, the choice of terminology and framing operates to narrate a “national story of peoplehood that minimizes, or even overlooks, division and conflict…”.[5] In the English Syllabus, England’s contentious relationships with Scotland and England’s former colonies, including Ireland, are unnamed and therefore erased. Rather, themes which are redolent of linear progression or “accomplished progress” narratives are selected, mitigating against critical engagement with themes which may elicit cognitive or affective discomfort by challenging narratives of “imperial innocence”.[6] The ‘Continuity State’ narrative thus serves to (mostly) gloss over a contentious, imperialist past and instead seeks to create the illusion of an united and collective ‘we’, that of one ‘British’ nation.

By contrast, the Scottish approach actively names dimensions of that contentious past, for example, The Wars of Independence, Migration and Empire, The Century of Revolutions and The Atlantic Slave Trade. This, at first glance, suggests a Scottish willingness to engage critically with a difficult past particularly the legacies of colonialism.

What is interesting and is noted by the article’s authors, however, is that more controversial themes like the Transatlantic Slave Trade, in which the Scottish nation is directly implicated, are siloed into the ‘British’ unit and therefore positioned as British rather than Scottish atrocities. This omission as the authors note is curious given the centrality of the city of Glasgow to the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Thus, while the controversial and contested nature of the past is acknowledged in Scottish curricular themes, the dehumanising and morally bankrupt actions of slavery are relegated to the British (not Scottish) unit. This ‘Split-Screen Approach’ and “historical forgetting”[7] thus serves a specific political function. It works to (re)produce a positive nationalistic view of Scotland’s past, one not implicated in the atrocities of colonialism.

I found the authors’ analysis both interesting and thought-provoking. As I finished reading this article, I reflected on the fact that it is not only the official curriculum that matters, but also the enacted and received curricula, which always differ from what is intended. I wondered about how these history curricula are accepted, negotiated, and contested by English and Scottish teachers and students and also how these differentially framed curricula (in tandem without variables including family, peer-groups, recent political events) shape and constrain teachers’ and students’ worldviews, identities and political agency. While consideration of the framing of Britain within curriculum documents is both important and worthwhile, attention to how this content is enacted, negotiated and contested in the classroom would provide rich learnings for history educators and practitioners.

____

References

[1] Tota, A. L. & Hagen, T. (2016). Introduction: Memory work: Naming pasts, transforming futures. In A. L. Tota & T. Hagen (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of memory studies (pp. 1-6). Routledge.; Taylor, T. & Guyver, R. (Eds.). (2011). History wars and the classroom: Global perspectives. Information Age Publishing.

[2] Lidher, S., McIntosh, M. & Alexander, C. (2021). Our migration story: History, the national curriculum, and re-narrating the British nation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47 (18), 4221–4237 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1812279; Sandhu, S., Harris, R. & Copset-Blake, M. (2023). School history, identity and ethnicity: An examination of the experiences of young adults in England. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 55 (2), 153-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1812279

[3] Sandhu et al., 2023, p. 155

[4] Staeheli, L. A. & Hammett, D. (2010). Educating the new national citizen: Education, political subjectivity, and divided societies. Citizenship Studies, 14 (6), 667-680.

[5] Staeheli & Hammett, 2010, p. 673

[6] Lidher et al., 2021, p. 4222

[7] Lidher et al., 2021, p. 4221