from our “Wilde 13” section

Abstract: This text describes a public history project focused on the University of Rosario in Colombia and its links to slavery. The project aims to critically examine archival documents and highlight the workings of racial oppression in Colombian history. It includes a walking tour of the University’s cloister and an art exhibit featuring contemporary Afro-Colombian artists. The project hopes to provide insights into the experiences of the victims of history and it will involve both physical and digital formats.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21186

Languages: Spanish, English

¿Cuáles son las conexiones entre la Universidad del Rosario, una de las más antiguas y prestigiosas instituciones de educación superior de Colombia, y la institución de la esclavitud? Este proyecto de historia pública explora los archivos de la universidad para examinar cómo la dominación étnica/racial jugó un papel central en la historia de la Universidad. El proyecto incluye un tour guiado y una exhibición de arte titulada “Quitarse la venda de los ojos” que muestra cómo las historias afrocolombianas e indígenas han permanecido ocultas a plena vista.

Hagiografías institucionales

El Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario -fundado en 1652- fue una de las primeras universidades de la Nueva Granada colonial y todavía sigue siendo apreciada como una de las instituciones de educación superior más prestigiosas de Colombia. No es sorprendente, entonces, que el Archivo Histórico de la Universidad sea extremadamente valioso, ya que contiene miles de documentos originales -tanto textos manuscritos como impresos- que pueden ayudarnos a lograr una mejor comprensión de los procesos socio-culturales que han marcado la historia de la nación. Sin embargo, estos documentos se han utilizado hasta ahora principalmente para ilustrar celebraciones institucionales, historias que generalmente carecen de una perspectiva crítica. Así, la mayoría de las publicaciones basadas en investigaciones realizadas en el Archivo Histórico han tendido a pasar por alto, por ejemplo, las diversas formas de exclusión social -vinculadas a la clase, la etnia y el género-, que han caracterizado tanto la historia del país como la de la universidad.

Nuestro proyecto, que comenzó en junio de 2021, tiene como objetivo examinar en detalle y críticamente algunos de los documentos de archivo disponibles, para reflexionar sobre las diversas formas en que la dominación étnica/racial ha jugado un papel central en la historia de la Universidad. Por un lado, el Colegio Mayor se ha beneficiado -desde su misma fundación en el siglo XVII y hasta el siglo XIX- del trabajo, los productos y las ganancias de la esclavización de personas de origen o ascendencia africana esclavizadas, así como de otras formas de trabajo no libre que implican la explotación de los grupos indígenas. Por otro lado, la Universidad fue explícitamente diseñada para educar a los descendientes de los conquistadores, requiriendo que todos los estudiantes demostraran su limpieza o pureza de sangre.

Este proyecto de investigación e historia pública tiene como objetivo resaltar el funcionamiento de la opresión racial en la historia colombiana colonial y republicana temprana. También esperamos que proporcione perspectivas sobre las experiencias de las personas victimizadas por esa historia, incluyendo tanto a las personas de origen o ascendencia africana esclavizadas, como a los grupos indígenas cuyas vidas fueron profundamente trastornadas por la colonización de su tierra después de la conquista. El proyecto incluye dos componentes de historia pública.

El primero es un recorrido guiado por catorce puntos del Claustro del campus principal de la Universidad, realizado en colaboración con el Museo Universitario (MURO) y el Archivo Histórico, y en el cual se utilizan los materiales de archivo generados por el proyecto. El segundo es una Exposición de Arte titulada “Quitarse la venda de los ojos”, que presenta artistas afrocolombianos contemporáneos interesados en la historia y en el legado de la esclavización en Colombia. El recorrido está disponible tanto en formato físico como digital, este último basado en un Proyecto de Humanidades que se pondrá a disposición del público en 2023 para celebrar el aniversario 370 de la Universidad.

Un recorrido guiado

El recorrido a pie comienza en la estatua del fundador de la universidad, Fray Cristóbal de Torres y Motones (1573-1654), situado en el centro del claustro. La primera parada utiliza los documentos fundacionales de la Universidad representados por las Constituciones que detenta la estatua de Fray Cristóbal, para evidenciar la estrecha conexión entre la historia de la Universidad, desde sus inicios, con la esclavización de las personas de origen o ascendencia africana y con la explotación de los pueblos indígenas. Significa que, contrariamente a los imaginarios prevalecientes en Colombia, el Colegio Mayor puede ser reinterpretado como un lugar significativo para las historias afrocolombiana e indígena.

En este sentido se puede decir que esta parte de su historia institucional ha permanecido “oculta a plena vista”, frase acuñada en un informe de 2006 por la Universidad de Brown para definir cómo los vínculos de las universidades con el proceso de esclavización a menudo han sido pasados por alto, a pesar de ser fácilmente evidentes.[1] El Colegio Mayor, como muchas otras universidades con orígenes coloniales en todas las Américas, aún tiene que examinar a su pesar sus propias conexiones históricas con la esclavización y la trata transatlántica de personas de origen o ascendencia africana, ya que éstas son fundamentales para su historia.

En la segunda parada los visitantes ingresan a otro edificio conocido como la Casa Rosarista, que tiene una serie de habitaciones que llevan el nombre, sin mucho pensamiento crítico, de las haciendas que la Universidad solía poseer. Allí los visitantes aprenden sobre el papel crucial que jugaron las personas esclavizadas en el establecimiento y sostenibilidad de la Universidad durante casi dos siglos (1653-1834). Además, los visitantes llegan a comprender que esta historia de esclavización está entrelazada con la violencia contra los pueblos indígenas, particularmente a través de los sistemas de encomienda y concierto.[2]

La tercera estación se centra en el tema de la libertad y destaca la importancia de las comunidades cimarronas y las fugas en la historia de la esclavización (incluso en Bogotá, ciudad y región que generalmente está ausente en las representaciones públicas de la historia de la esclavización en Colombia), así como la necesidad de reconocer diferentes formas de la resistencia.

Las paradas cuarta y quinta, ubicadas donde se encontraban la antigua cocina y los dormitorios, brindan la oportunidad de reconocer que la esclavización era parte de la vida diaria dentro del claustro en ciertos momentos y que había presencia de personas de origen o ascendencia africana e indígenas alrededor de la Universidad -un espacio tradicionalmente representado como blanco- tanto durante la época colonial como en tiempos republicanos.

Las parada sexta y séptima. Ubicadas en la antigua oficina de la rectoría y en la capilla de la Universidad, promueve un examen honesto y abierto de la violencia brutal inherente a la esclavización, actualmente reconocida como un crimen contra la humanidad y del complejo papel de la iglesia en la historia de la opresión racial.

Las octava, novena y décima paradas se ubican en el archivo de la Universidad y en la biblioteca, en la placa en honor a Luis Antonio Robles, un colegial afrocolombiano del siglo XIX. Su propósito es suscitar una reflexión crítica sobre la práctica de honrar a personas racializadas del Colegio Mayor, haciendo visible el hecho de que muchas veces han sido silenciados en las narrativas institucionales, así como la significación de los archivos -con todos sus sesgos y silencios- para investigar estas historias. Estas tres paradas pretenden enfatizar la triple violencia histórica que sufrieron los pueblos esclavizados a lo largo de su vida, en los archivos y en libros de historia institucional.

Las siguientes estaciones se enfocan más en los esclavizadores que en los esclavizados: la undécima parada -ubicada en la sala más ceremonial de la Universidad, el Aula Máxima,- destaca el papel de los miembros de la Universidad (y no sólo de la institución misma) en la perpetuación de la esclavización. En las paradas duodécima y décimotercera, situadas cerca de las placas que honran la memoria de Francisco José de Caldas (destacado intelectual criollo) y José Celestino Mutis (el líder español de la Real Expedición Botánica de 1783 a 1816), resaltan las conexiones cercanas entre intelectuales asociados con el Colegio Mayor que son venerados como ellos, y la institución de la esclavitud así como otras formas de opresión racial.

La última parada del recorrido es un pedestal desocupado situado en la entrada principal de la universidad (la llamada Plaza del Rosario), donde se encontraba la estatua del conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, la cual solía estar en pie antes de ser derribada por los indígenas Misak en el marco de las protestas sociales de 2021. Este lugar sirve como una conclusión apropiada para el recorrido y como reflexión inspiradora sobre los efectos duraderos de la esclavización y sobre la historia étnico-racial del país después de 1851.

Arrojando luz sobre la vida de los esclavizados

En cada parada del recorrido, nuestro objetivo es arrojar luz sobre la vida de los hombres, mujeres e hijos esclavizados que trabajaron y vivieron en el Colegio Mayor o en sus haciendas. Nuestro objetivo es contar sus historias singulares y enfatizar su humanidad, reconociendo al mismo tiempo las dificultades que enfrentaron y su búsqueda de la libertad.

Sin embargo, dar vida a sus historias y experiencias no es una tarea fácil. La razón es simple: en general, lo que sabemos sobre ellos proviene sólo de lo que los propietarios de personas esclavizadas escribieron. Esto significa que las fuentes tienden a mencionar únicamente los aspectos de sus vidas que eran de interés para sus esclavizadores. Siempre podemos hablar de una “violencia de las fuentes” en historias marcadas por el colonialismo. En el caso de la esclavización la situación es extrema, ya que los registros disponibles reducen explícitamente a las personas esclavizadas a su condición de “propiedad”. Por ejemplo, la mayoría de las personas esclavizadas han entrado en los registros históricos de la Universidad (y, posteriormente, en su historia) sólo porque fueron mencionados como “propiedad” o “mercancías” registradas en inventarios, así como en registros de compra y venta.

La violencia de los archivos

Como resultado, los investigadores contemporáneos que intentan reconstruir la vida de las personas esclavizadas encuentran que los documentos disponibles a menudo dificultan más que facilitan sus esfuerzos por comprender estas experiencias. Estos documentos tienden a crear una situación paradójica donde la disponibilidad de los archivos genera oportunidades para los investigadores interesados en aproximarse a estas experiencias silenciadas, pero también frustración dado el hecho de que actúan como una pantalla o como un espejo deformado. Los archivos de la esclavización no sólo contienen evidencia de la violencia ejercida sobre las personas esclavizadas (tanto en sus mentes como en sus cuerpos): son otra instancia de violencia dentro del proceso de esclavización.

Ante esos silencios y violencias presentes en los fragmentarios registros históricos que han sobrevivido, nuestra única opción es escribir la historia con incertidumbre, problemas sin resolver y contradicciones. A menudo, ni siquiera tenemos los nombres de las personas cuyas vidas buscamos comprender. Sin embargo, debemos reconocer que estos individuos no son seres abstractos sino personas con dignidad e intereses propios. Para dar cuenta de esta tarea imposible hemos tratado de seguir ejemplos de académicos como el de Saidiya Hartman o el de Marisa Fuentes, quienes nos invitan a acercarnos a los archivos violentos con una mirada crítica y ética, que dé cuenta del trauma y la violencia que contienen, y a relacionarnos con ellos en una forma que centra las experiencias y la dignidad de quienes fueron objeto de violencia y opresión.

_____________________

Bibliografía

- Fuentes, Marisa J. Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

- Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14.

- Vergara Figueroa, Aurora and Cosme Puntiel, Carmen Luz, eds. Demando mi libertad: Mujeres negras y sus estrategias de resistencia en la Nueva Granada, Venezuela y Cuba, 1700-1800. Cali, Colombia: Universidad Icesi, 2018.

Vínculos externos

- Un caso de reparación: http://uncasodereparacion.altervista.org/ (visitado el 26 de marzo de 2023).

- President’s Commission on Slavery and the University: https://slavery.virginia.edu/universities-studying-slavery-uss-the-birth-of-a-movement/ (visitado el 26 de marzo de 2023).

- Brown & Slavery & Justice: https://slaveryandjustice.brown.edu/ (visitado el 26 de marzo de 2023).

_____________________

[1] https://slaveryandjusticereport.brown.edu/sections/slavery-the-slave-trade-and-brown/ (last accessed 26 March 2023). La exhibición “hidden in plain sight” fue curada por el Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, un centro de investigación con una misión de humanidades públicas creado a partir del reporte “Slavery and Justice” en 2006t. El de Brown ha sido considerado un modelo para otras universidades examinando sus propias coneciones históricas con la esclavitud: https://cssj.brown.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/16777_CSSJ_Uhall_Brochure.pdf (last accessed 26 March 2023).

[2] La encomienda fue un sistema por medio del cual la corona española compensaba a los colonizadores otorgándoles acceso a mano de comunidades indígenas que eran obligadas a trabajar para ellos a cambio de evanvelización y protección militar. El concertaje fue un sistema contratación que aseguraba a los españoles la mano de obra indígena a través de un “contrato de concierto”.

_____________________

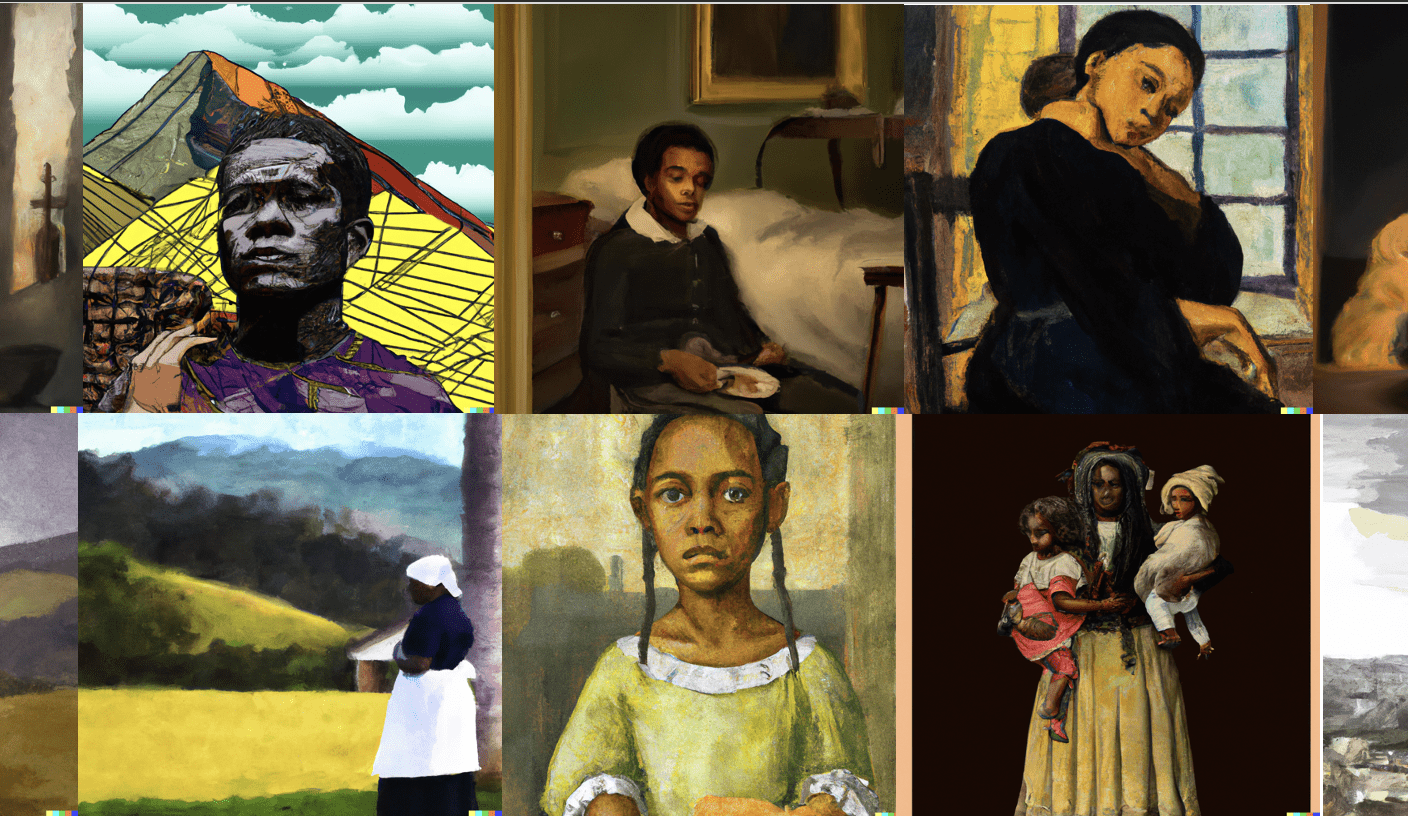

Créditos de imagen

Image created with AI, Dall-e 2: Project La Universidad del Rosario y sus vínculos con la institución de la esclavitud: investigaciones archivísticas y procesos memoriales 2023

Citar como

Bosa, Bastien, and Diana Angulo: Revelando el pasado: Las vidas esclavizadas importan. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 2, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21186.

Responsabilidad editorial

What are the historical links that the Universidad del Rosario – one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Colombia – has had with the institution of slavery? This public history project delves into the Colegio Mayor‘s archives to examine how ethnic/racial domination played a central part in the University’s history. The project includes a walking tour and an art exhibit entitled “Taking the Blindfold Off,” showing how the Afro-Colombian and Indigenous histories have remained hidden in plain sight.

Institutional Hagiographies

The Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario – founded in 1653 – was one of the first universities in colonial New Granada, and it has remained, up until today, one of the most prestigious institutions of higher education in Colombia. Unsurprisingly, the Historical Archive of the University is extremely valuable: it contains thousands of original documents – both manuscripts and printed texts – that can help us to gain a better understanding of the socio-cultural processes that have marked the history of the nation. Yet, these documents have been mainly used, so far, to write celebratory institutional histories, that generally lack a critical perspective. Most publications based on research conducted in the Archivo histórico have tended to overlook, for example, the various forms of social exclusions – linked to class, ethnicity and gender – that have characterized both the history of the country and that of the University.

Our project – which started in June 2021 – aims at examining in detail and critically some of the available archival documents, to reflect upon the various ways in which ethnic/racial domination has played a central part in the history of the University. On the one hand, the Colegio Mayor has benefited – from its very foundation in the 17th century and until the 19th century – from the labor, products, and profits of the enslavement of peoples of African descent, as well as other forms of unfree labor involving the exploitation of Indigenous groups. On the other hand, the University was explicitly designed to educate the descendants of the Conquistadores, requiring all students to demonstrate their limpieza de sangre (or blood purity).

This research and public history project aims to highlight the workings of racial oppression in colonial and early republican Colombian history. We also hope that it will provide insights into the experiences of the victims of that history, including both people of African descent affected by the transatlantic slave trade and Indigenous groups, whose lives were profoundly disrupted by the colonization of their land following the Conquista.

The project includes two public history components. The first one is a 14-stop guided tour of the Cloister in the main campus of the University, conducted in partnership with the University Museum (MURO) and the Historical Archive, and utilizing the archival materials generated by the project. The second one is an art exhibit titled “Taking the Blindfold Off” which features Afro-Colombian contemporary artists interested in the history and legacy of enslavement. The tour is available in both a physical and digital format, the latter one based on a digital humanities project that will be made publicly available in 2023 to mark the University’s 370th anniversary.

A 14-stop Walking Tour

The guided tour begins at the statue of University founder, Fray Cristobal de Torres y Motones (1573-1654), located in the center of the Cloister. The first stop uses the University’s founding documents, represented by the Las Constituciones held by the statue of Fray Cristobal, to evidence the close connection between the history of the University from its inception, and the enslavement of persons of African descent and exploitation of Indigenous peoples. It means that, contrary to prevalent imaginaries in Colombia, the Colegio Mayor can be reinterpreted as a significant location for Afro-Colombian and Indigenous histories.

We could say, in this sense, that this part of its institutional history has remained “hidden in plain sight”, a phrase coined in a 2006 report by Brown University to describe how that Universities’ ties to enslavement have often been overlooked despite being readily apparent.[1] The Colegio Mayor, like many other universities with colonial origins all over the Americas, has yet to examine its own historical connections to enslavement and the transatlantic slave trade, despite these connections being central to its history.

At the second stop, visitors enter another building known as the Casa Rosarista, which has a series of rooms named, without much critical thought, after the haciendas the University used to own. There, the visitors learn about the crucial role enslaved people played in the establishment and sustainability of the University during nearly two centuries (1653-1834). Additionally, the visitors come to understand that this history of enslavement is intertwined with violence against Indigenous peoples, particularly through the encomienda and concierto systems.[2]

The third station focuses on the theme of freedom and highlights the significance of maroon communities and escape in the history of enslavement (including in the Bogotá region, which is generally absent in the public representations of the history of enslavement in Colombia), as well as the need to acknowledge different forms of resistance.

The fourth and fifth stops, located where the former kitchen and dormitories were situated, provide a chance to acknowledge that enslavement was a part of daily life within the Cloister at certain times and that there was presence of Afro-descendants and Indigenous peoples around the University—a space traditionally represented as white—during both colonial and republican times.

The sixth and seventh stops, located at the former chancellor’s office and at the University chapel, encourage an honest and open examination of the brutal violence inherent to enslavement, now recognized as a crime against humanity, and the complex role of the Church in the history of racial oppression.

The eighth, ninth, and tenth stops are located at a plaque honoring one of the few Afro-Colombian students from the 19th century called Luis Antonio Robles, at the University archives, and in the library. Their purpose is to prompt critical reflection on the practice of honoring racialized individuals at the Colegio Mayor, making visible the fact that they have often been silenced in institutional narratives, as well as the significance of archives—with all their biases and silences—to research these histories. These three stops aim to emphasize the triple historical violence that enslaved people endured: throughout their lives, in the archives, and in institutional history books.

The following stations focus more on the enslavers than on the enslaved: the eleventh stop—located in the most ceremonial room of the University: the Aula máxima—highlights the role of the University members (and not just the institution itself) in perpetuating enslavement; the twelfth and thirteenth stops, situated near plaques honoring the memory of Francisco José de Caldas (a prominent criollo intellectual) and Mutis (the Spanish leader of the Royal Botanical Expedition of 1783 to 1816), underscore the close connections that revered intellectuals like them, associated with the Colegio Mayor, had with the institution of slavery and other forms of racial oppression.

The final stop on the tour is an unoccupied pedestal situated at the front entrance of the University (in the so-called plaza del Rosario), where the statue of the Conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada used to stand before it was removed by Misak Indigenous people protesters in 2021. This spot serves as an appropriate conclusion to the tour, inspiring reflection on the enduring effects of enslavement and the ethno-racial history of the country post-1851.

Shedding Light on the Lives of the Enslaved

At each stop on the tour, we aim to shed light on the lives of the enslaved men, women and children who lived and worked at the Colegio Mayor or its Haciendas. Our goal is to recount their singular stories and to emphasize their humanity, while recognizing the hardships they faced and their pursuit of freedom.

Bringing to life their stories and experiences is not an easy task, though. The reason is simple: in general, what we know about them comes only from what the slaveholders wrote. This means that the sources tend to mention only the aspects of their lives that were of interest to their “masters”. We can always speak of a “violence of the sources” in histories marked by colonialism. In the case of enslavement, the situation is extreme since the available records explicitly reduce enslaved people to their status as “property”. For example, most enslaved persons have entered the historical records of the University (and, subsequently, its history) only because they were mentioned as “property” or “merchandise”, listed in inventories, as well as purchase and sale records.

The Violence of the Archives

As a result, contemporary researchers struggle to reconstruct the lives of many enslaved individuals, and the available documents often hinder rather than help our understanding of their experiences. These documents tend to create a paradoxical situation where their availability generates possibility for researchers interested in approaching these silenced experiences, but also frustration given the fact that they act as a screen or a distorting mirror. The archives of enslavement do not just contain evidence of the violence exercised on enslaved people (both on their minds and their bodies): they are yet another violence within the enslavement process.

Given those silences and violence present in the fragmentary historical records that have survived, our only option is to write history with uncertainty, unresolved issues, and contradictions. Often, we do not even have the names of the people whose lives we would like to understand. Nevertheless, we must recognize that these individuals were not abstract beings but persons who had their own dignity and interests. To realize this impossible task, we have tried to follow the examples of scholars like Saidiya Hartman and Marisa Fuentes, who invite us to approach violent archives with a critical and ethical lens that acknowledges the trauma and violence that they contain, and to engage with them in a way that centers the experiences and dignity of those who were subjected to violence and oppression.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Fuentes, Marisa J. Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

- Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14.

- Vergara Figueroa, Aurora and Cosme Puntiel, Carmen Luz, eds. Demando mi libertad: Mujeres negras y sus estrategias de resistencia en la Nueva Granada, Venezuela y Cuba, 1700-1800. Cali, Colombia: Universidad Icesi, 2018.

Web Resources

- Un caso de reparación: http://uncasodereparacion.altervista.org/ (last accessed 26 March 2023).

- President’s Commission on Slavery and the University: https://slavery.virginia.edu/universities-studying-slavery-uss-the-birth-of-a-movement/ (last accessed 26 March 2023).

- Brown & Slavery & Justice: https://slaveryandjustice.brown.edu/ (last accessed 26 March 2023).

_____________________

[1] https://slaveryandjusticereport.brown.edu/sections/slavery-the-slave-trade-and-brown/ (last accessed 26 March 2023). An exhibition called “hidden in plain sight” was curated by the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, a scholarly research center with a public humanities mission that was created out of the 2006 “Slavery and Justice” report. Brown has been considered a model for other universities to follow in examining their own historical connections to slavery: https://cssj.brown.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/16777_CSSJ_Uhall_Brochure.pdf (last accessed 26 March 2023).

[2] The encomienda system was a labor system in which indigenous peoples were forced to work for Spanish colonizers, while the concierto system was a system of forced labor and tribute payments in which indigenous communities were required to provide labor and resources to local colonial authorities.

_____________________

Image Credits

Image created with AI, Dall-e 2: Project La Universidad del Rosario y sus vínculos con la institución de la esclavitud: investigaciones archivísticas y procesos memoriales 2023

Recommended Citation

Bosa, Bastien, and Diana Angulo: Unveiling the Past: Enslaved Lives Matter. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 2, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21186.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 2

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21186

Tags: Colombia, Indigenous Peoples (Indigene Völker), Language: Spanish, Racism (Rassismus), Slave History (Geschichte der Sklaverei), South America (Südamerika)

German version below. To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Public history, silences and archival violence

The approach suggested by the authors is very interesting to consider and comment on. The exercise involves approaching the lives of enslaved men, women and children through parts of stories, as of yet untold, of racial oppression connected to the historical trajectory of the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario in Colombia. The institutional archive included in the study offers both possibilities and restrictions, and is also considered as a subject.

This is a descriptive article in which the elements and concepts of a public history practice are first outlined. Said practice will include a guided walking tour and an art exhibition. Of these, only the former is developed by proposing a very interesting tour among immovable and movable heritage, institutional history, the documentary traces of a historical archive and the remembrance of hidden, silenced, unspoken stories. Visitors will be invited to several departments of the university, where keys of analysis will throw into question the institution’s apparently unambiguous reading. That the tour ends around a fallen statue (it was toppled during the social protests of 2021) says a lot about the exercise: it is proposed from the present, its position is critical, and it involves a public space. At the same time it forces an entire community, an entire society, to reconfigure its perception of that obsolete space; a space that cannot possibly be interpreted in any other way even with the same background and documents that today serve to sustain this interpretation. We also read that Bogotá’s Instituto Distrital de Patrimonio (District Heritage Institute) decided to move the statue to a museum in the city a few months after it was toppled over and following a process of consulting with citizens.[1]

We would like to point out one element from the article that would be good to put to the test: the historical archive has served only institutional history and the research included in the archive has not addressed social exclusion as a topic. This criticism can be interpreted in at least two ways: that the practice of historical research has not engaged in new theoretical and methodological approaches or the archive still has a markedly institutional function.

Will it be possible to build a critical history with the institutional archive? What will history and institutional policies do with it? The historiography of the last decades and the examples proposed by the authors from other university institutions seem to answer that it is possible, that the presence of new demands and social struggles can lead institutions to develop practices of recognition, revision and historical reparation, and that these can transform into university programs and policies.

Where are the experiences of enslaved men, women and children recorded? Undoubtedly, the archive can serve as a tool to approach tangentially the lives of those who were not included. And the fact is that the archive, as a set of documents and as a source of information during the initial era of this institution, served other functions and agents, who held command in terms of documentation and power, and required the documents and information to manage their affairs.

I would like to end this brief reflection with some questions that can open new doors around these issues. Who do the documents and the archives of a university serve, and what functions do they fulfill in this century? Who chooses, what is valued and chosen, who can access it, what is presented? If the university, its institutional archive and the documents take or took part in the violence, what characteristics do they possess today? What do we want them to be like? According to Cook[2], silences still occur within the relationships between researchers and archivists.

_____

[1] https://idpc.gov.co/nueva-ubicacion-estatua-de-gonzalo-jimenez-de-quesada, (last accessed 30 March 2023).

[2] Cook, Terry. Panoramas del pasado: archiveros, historiadores y combates por la memoria (Panoramas of the past: archivists, historians and battles for memory). Tabula, (13). Retrieved from https://publicaciones.acal.es/tabula/article/view/257 2-03-2023 (last accessed 30 March 2023).